The COVID-19 pandemic has thrown quite a lot of the problems the health sciences community is facing into sharp relief. Questions of equity, access, and resource allocation have all had their turn. While science communication has been a concern throughout the pandemic, the announcement that everyone 16 and older in the United States is now eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine has foregrounded the need to communicate efficiently and effectively with the general public. Drs. Emily Smith and Heather Young with the Milken School of Public Health have been working hard to communicate COVID-19 information to the general public since the beginning of the pandemic. I took this opportunity to speak with them about their experiences, and to ask their advice for how best to work with the public to combat misinformation and encourage those who might be vaccine hesitant to get vaccinated.

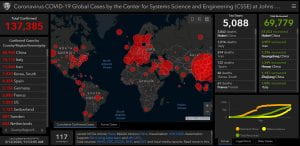

In early 2020, as the new SARS-CoV-2 virus spread around the globe, Dr. Smith noticed the questions her friends, family, and even strangers were posing on the internet. Often these were the same questions - what preventative measures can I take, what do I do if I or a family member think we have it, what is my risk, etc. Because the data and information were so new and this was a rapidly evolving situation, those without a health sciences background were encountering information that just wasn’t written for them. Even her fellow scientists were asking where information was coming from, since everything at this stage was coming from preprints and sourcing reliable numbers was vital. There was a clear need for someone to step in and help translate the science in a way anyone could understand, and to aggregate it into one central location that linked back to primary scientific literature. Thus, COVID-101.org was born. Dr. Smith and a few colleagues established the website as a resource they and their fellow science communicators could link to when asked these questions.

The backbone of COVID-101.org is its review process. Not only do scientists and experts write the articles answering questions and referencing primary scientific literature, their colleagues provide peer review before posting the articles. This is where Dr. Young comes in. Early on in the pandemic, Dr. Young gave a lecture to a group of medical students breaking down the basics of epidemiology. Dr. Smith had recently launched COVID-101.org, and sent out an email asking for contributions. Dr. Young adapted her lecture and submitted it, and she continued collaborating with the other volunteers working on COVID-101.org, both writing and reviewing posts. And that’s one of the key things to remember about COVID-101.org, that all of the contributors are volunteers. Everyone from epidemiologists to undergraduates to web developers, all are volunteering their time and talents. Both Drs. Smith and Young think of this as a silver lining - getting to connect with everyone working on the site, old colleagues and new.

As the pandemic progressed, Drs. Smith and Young saw the purpose of COVID-101.org shifting. In the early days, the site served as an aggregator, compiling information and responding to questions. Dr. Young recalls a specific pivotal moment in the evolution of the site: “When President Trump had his bleach injection moment, it was one of those times where five or six of us jumped on the Slack channel and were like ‘we have to get something out there, it has to be out there quick’... we kind of shifted gears from waiting for people to ask us stuff and decided that we needed to go put a message out there that we thought was important.” A little over a month later, COVID-101.org published a post on the social justice movement and why people may decide to protest during the pandemic, describing the “dual pandemic” of racial injustice and COVID-19. These two instances compelled COVID-101.org contributors to take a more active role in creating messaging and putting accurate information where the public could find it.

When they started working on COVID-101.org, neither Dr. Smith nor Dr. Young had extensive experience with science communication. Dr. Smith had some experience in her work with the Gates Foundation, translating scientific data and information for policy makers. Dr. Young, on the other hand, didn’t have any “formal” experience, though she believes teaching requires a similar mindset of distilling complex information in a way students can understand. I asked what they had learned through this process, and what advice they might have for others in the health sciences community who are trying to counter misinformation and, in particular, address vaccine hesitancy.

Both Dr. Smith and Dr. Young described two important things they’ve taken away from their work on COVID-101.org. First, you want to encourage people when they do ask a question. Let them know it’s a good thing that they have this question. Lead with that attitude, and people will be more receptive to your answer. Understand that the misinformation people encounter may have a kernel of truth in it. Acknowledge that, without dismissing their concerns or mocking whatever misinformation it is. As Dr. Young said, you have to “meet people where they are.” Have a conversation with them, rather than lecturing them. Frame the conversation as a way to equip them with information to come to their own decisions rather than convincing them one way or another. Second, you need to make your answer specific to a person’s life. Dr. Smith recalls one of the earliest posts on COVID-101.org:

One of the first posts we put out before things were shut down was “no you shouldn’t go to a large gathering.” And the questions we got in response were things like “Can I go to this concert?” or “Can I go to this game?” These follow up questions that, to me, should have already been answered by the post. But it wasn’t specific enough, and it wasn’t specific to their life. As a scientist it feels kind of duplicative or I worry that it’s too much the same, but I think that’s one of the valuable ways that we can add here and same for anyone trying to communicate with other people.

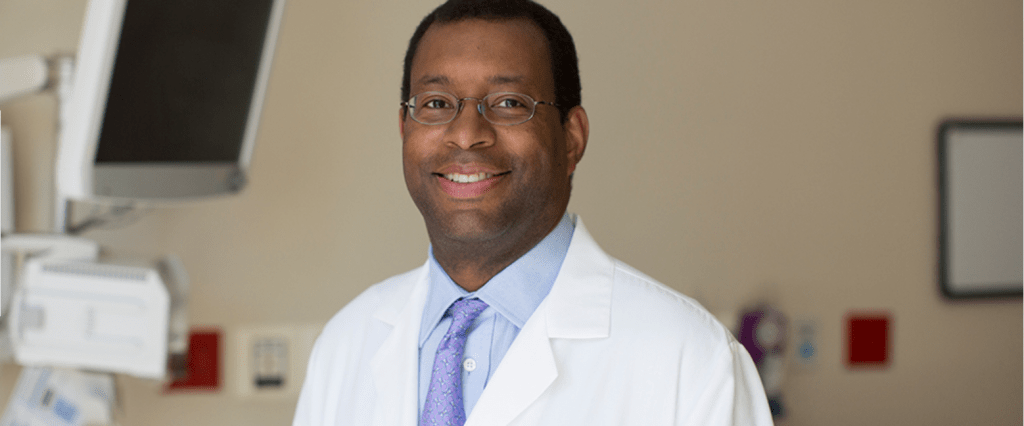

Dr. Emily Smith

Dr. Young echoed this, describing the need to “repeat and repackage” for individuals. Everyone is approaching risk assessment and the pandemic with their own lived experiences. If we can make our information relevant to their experiences, it makes it easier for them to incorporate that information into their lives. A recent concept introduced on COVID-101.org, the risk budget, can help people situate the information they are getting within the context of their own life.

Not all of our work combating misinformation or vaccine hesitancy occurs with people on the internet, however. Quite often friends and family members will come to those of us who work in the health sciences with their questions, seeing us as a trusted and valuable source. While the information you’re providing doesn’t change, having that pre-existing relationship with someone can make it easier to encourage them to think critically about the misinformation they’ve encountered. Dr. Young describes telling friends and family “Well, okay, maybe you don’t trust the scientists in the lab, but you trust me, right? And I’m not going to tell you to do something that I legitimately would think is harmful.” Dr. Smith also sees the opportunity to give people the facts “within the context of their life.” You know these people and can tailor your response in a way that makes sense to them.

So how do we best communicate with our friends, family, and even strangers? It’s a difficult line to walk, and one that is becoming increasingly important as access to the COVID-19 vaccine expands. The best thing you can do is prepare yourself with readily available resources. Of course, COVID-101.org is an excellent place to start. If you can’t find an answer to your question, you can always ask them. Himmelfarb Library has also put together a Correcting Misinformation with Patients Research Guide. It has tons of resources, information on communication techniques, and even specifically addresses vaccine hesitancy. The Conversation: Between Us, About Us video series from the Kaiser Family Foundation and Black Coalition Against COVID is a living video library and a phenomenal resource for the black community featuring answers from black scientists, black doctors, and black nurses. While The Conversation's target audience is the black community, the information is clearly communicated and could be useful to others. NIH’s Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) has some great resources focused on engaging communities most at risk. If you’re looking for continuing education (CE) opportunities, LearnToVaccinate.org has a number of CE activities related to patient communication. This is a pivotal moment for the health sciences community, and we as a whole need to be ready to answer questions empathetically and accurately. There has already been a great deal of progress and reason for optimism - over 50% of US adults have had at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Armed with these resources, we can meet the general public and encourage everyone to get fully vaccinated. And hopefully we can harness the tools and lessons learned from the pandemic and apply those to other areas of science communication. The more informed the public is the more we are all empowered to make the right decisions for our health and the health of our communities.

As always, if you have any questions you can reach us via email at himmelfarb@gwu.edu. If you’re interested in volunteering on the COVID-101.org project, reach out via the Ask Us page on the site.