We’ve been getting a lot of questions recently about Open Access (OA) journals, and predatory journals, and how to tell the difference between them. Navigating the publishing landscape is tricky enough without having to worry about whether or not the journal you choose for your manuscript might be predatory. The concept of predatory journals may be completely new to some researchers and authors. Others who are aware of the dangers of predatory journals might mistake legitimate scholarly OA journals as predatory because of the Article Processing Charges (APCs) charged by OA journals. In today’s post, we’ll explore the differences between OA journals and predatory journals, and how to tell the difference between them.

Open Access Journals

The open access publishing movement stemmed from a need to make research more openly accessible to readers and aims to remove the paywalls that most research was trapped behind under that traditional publishing model. In a traditional, non-OA journal, readers must pay to access the full text of an article published in a journal. This payment may be through a personal subscription, a library-based subscription to the journal, or a single payment for access to a single article.

This video provides a great overview of why and how OA journals came about:

OA journals shift the burden of cost from the reader to the author by operating under an “author pays” model. In this model, authors pay a fee (often called an “Article Processing Charge” or APC) to make their articles available as open access. Readers are then able to access the full text of that article free of charge and without paying for a subscription. OA articles are accessible for anyone to read and without a paywall. The author fees associated with OA journals can range from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand dollars. OA journals charging APCs is completely normal and paying to publish in an open access journal is not itself a sign that the title is predatory in nature - this is normal practice for open access journals that helps publishers cover the cost of publication.

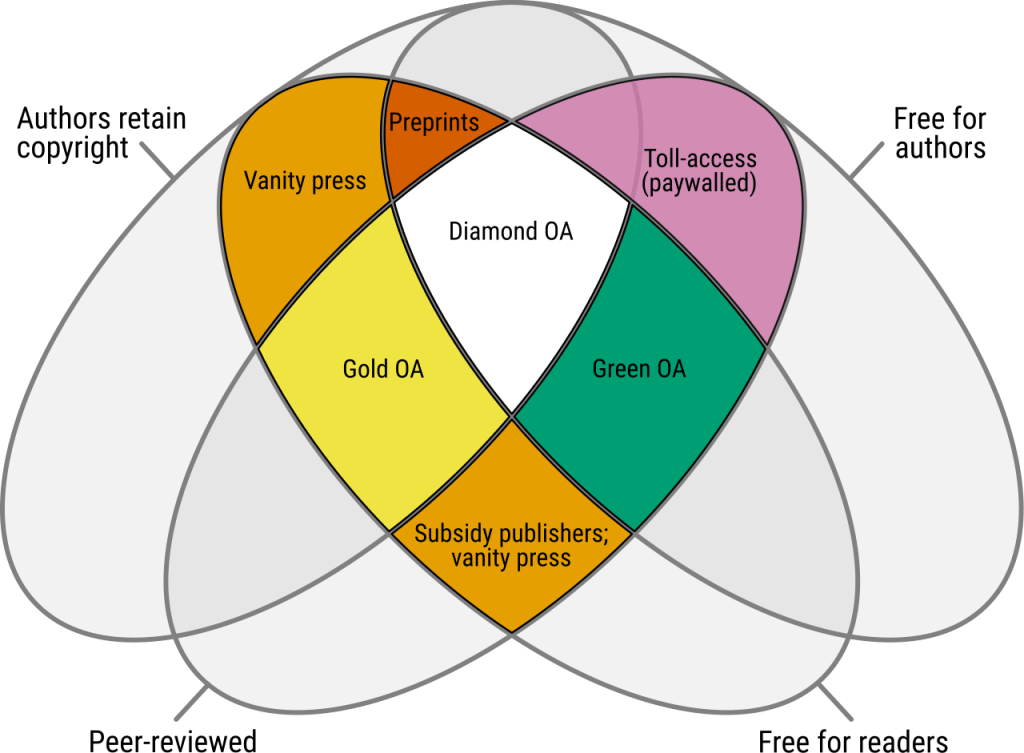

Open access journals offer all of the same author services that traditional journals offer, including quality peer review and article archiving and indexing services. Legitimate OA journals have clear retraction policies and manuscript submission portals. There are different types of OA journals, including journals that publish only OA articles, and hybrid journals that publish OA articles alongside articles that exist behind a paywall. To learn more about the types of OA research, check our recent blog post on Green, Gold, and Diamond OA models.

Predatory Journals

Predatory publishing came about as a response to the open access movement as unethical businesses saw OA journals as a way to make money off of researchers' need to publish. Predatory journals use the OA model for their own profit and use deceptive business practices to convince authors to publish in their journals.

One key difference between reputable, scholarly OA journals and predatory journals is that predatory journals charge APCs without providing any legitimate peer view services. This means that there are no safeguards to protect a quality research article from being published alongside junk science. Predatory journals typically promise quick peer review, when in reality, no peer review actually takes place.

When you publish with a legitimate OA journal, the journal provides peer review, archiving, and discovery services that help others find your work easily. Predatory journals do not provide these essential services. Publishing in a predatory journal could mean that your work could disappear from the journal's website at any time, making it difficult to prove that your paper was ever published in said journal. Additionally, because predatory journals are not indexed in popular databases such as Scopus, PubMed, CINAHL, or Web of Science, despite false claims to the contrary, other researchers may never find, read, and cite your research.

Some general red flags to look for include:

- Emailed invitations to submit an article

- The journal name is suspiciously similar to a prominent journal in the field

- Misleading geographic information in the title

- Outdated or unprofessional website

- Broad aim and scope

- Insufficient contact information (a web contact form is not enough)

- Lack of editors or editorial board

- Unclear fee structure

- Bogus impact factors or invented metrics

- False indexing claims

- No peer review information

To learn more about predatory journals, check out our Predatory Publishing Guide.

OA vs. Predatory: How to Tell the Difference

Luckily, identifying scholarly open access journals and predatory journals can be done if you know what to look for, including the red flags listed above. OA journals that are published by reputable publishers (such as Elsevier, Wiley, Taylor and Francis, Sage, Springer Nature, etc.) can be trusted. If a journal is published by a well-known, established publisher, it’s a safe bet that the journal is not predatory in nature. These well-known, large publishers have policies in place that predatory journals lack, including indexing and archiving policies, peer review policies, retraction policies, and publication ethics policies.

Learn more by watching our How to Spot a Predatory Journal tutorial:

Check out the assessment tools available in our Predatory Publishing Guide for more tools that can help you evaluate journals, emails from publishers, and journal websites. There are even some great case studies available on this page to put your newly learned skills into practice!

For questions about predatory journals, or to take advantage of Himmelfarb’s Journal PreCheck Service, contact Ruth Bueter (rbueter@gwu.edu) or complete our Journal PreCheck Request Form.