In the early 1980s there were official reports of once healthy, young, gay men falling severely ill and dying from an unknown illness. The first five reported cases included men ranging in age from 29 to 36, all displaying various symptoms and eventually developing pneumonia. In the summer of 1981, the CDC established a task force to study this new debilitating condition and since then researchers have worked diligently to understand and find treatment options. The condition and the virus that causes this illness were eventually named Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) respectively. Since its initial discovery, the spread of HIV has been classified as an pandemic and has impacted millions of people around the world. UNAIDS estimates that 79.3 million people have been infected with HIV since the beginning of the pandemic and as of 2020, approximately 37.7 million people currently live with HIV. While there is no vaccine available to prevent HIV, over the decades researchers have discovered treatment options to help individuals manage their symptoms. Through ongoing research and clinical trials, HIV/AIDS researchers have several promising leads that could potentially help with the creation of a safe and effective vaccine that will contribute to the end of this decades long pandemic.

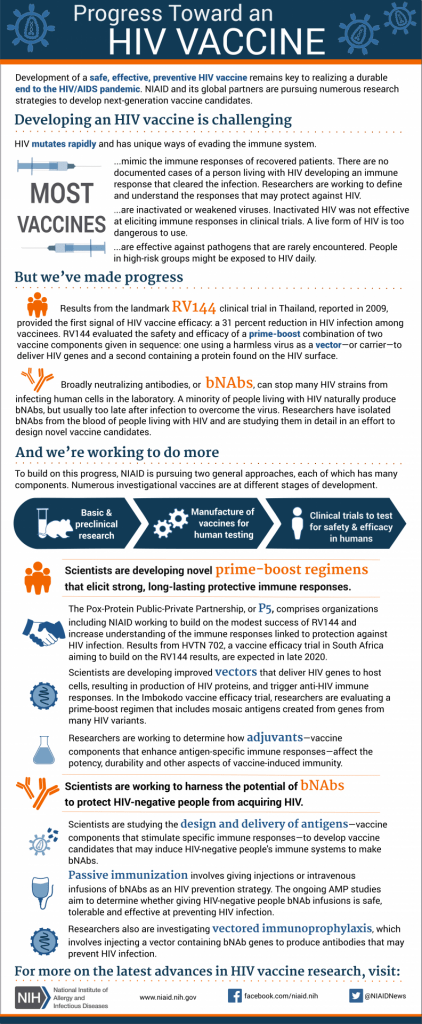

Researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) are actively studying HIV and how it interacts with people’s immune systems by conducting research and clinical trials. Using a two step, complementary approach towards vaccine development, researchers not only learn new information about the virus, but they also hope to use their findings to develop a vaccine that can be distributed to the general public. Under the empirical approach, researchers rely on observation and experimentation to move different vaccine candidates into the human trial stages. With the theoretical approach, researchers seek to better understand the virus, how it impacts the human immune system and how a vaccine can bolster the immune response when a person is exposed to HIV. These two approaches allow researchers to quickly move vaccine candidates through the different stages of clinical trials.

One of the most significant HIV vaccine clinical trials in recent years was the RV144 Trial in Thailand. This study enrolled over 16,000 volunteers and took place over the course of several years, with researchers reporting their findings in 2009. This trial showed that the vaccine candidates offered some protection against HIV in humans, which was the first time researchers discovered a vaccine could potentially protect people from the virus. The RV144 findings are still being analyzed for how the vaccine combination used in the trial helps our immune responses and other studies hope to build off the modest success of the RV144 trial. In the late 2010s, two other important clinical trials began and their data may offer a glimmer of hope for vaccine development. Launched in 2017 by the National Institutes of Health and other research partners, the HVTN 705/HPX2008 or Imbokodo study enrolled HIV-negative women in sub-Saharan Africa and used a vaccine regime “based on ‘mosaic’ immunogens–vaccine components designed to induce immune responses against a wide variety of global HIV strains.” (“NIH and Partners Launch HIV Vaccine Efficacy Study”) A complementary study called HPX3002/HVTN 706 or Mosiaco used a similar vaccine regime and took place across several countries including the United States, Brazil, and Poland. The Mosiaco study volunteers were made up of HIV-negative men and transgender people from the ages of 18 to 60. The results from the Imbokodo and Mosiaco studies were released in 2020 and 2021 respectively, though it may take years before researchers have a full understanding of the impact of these two clinical trials. In more recent news, NIAID scientists published an article in Nature Medicine that highlighted promising results of an HIV vaccine candidate based on the mRNA program used to develop vaccines for COVID-19. The researchers found that the vaccine showed promise in mice and non-human primates. According to Dr. Paolo Lusso, who led the team of researchers, "We are now refining our vaccine protocol to improve the quality and quantity of the VLPs (virus-like particles) produced. This may further increase vaccine efficacy and thus lower the number of prime and boost inoculations needed to produce a robust immune response. If confirmed safe and effective, we plan to conduct a Phase 1 trial of this vaccine platform in healthy adult volunteers..." ("Experimental mRNA HIV vaccine safe, shows promise in animals") It is difficult to predict when a vaccine will be available to the general public. But the results from clinical trials like the RV144 trial offer hope that one day researchers will create a safe vaccine and bring an end to this decades long pandemic.

Our understanding of HIV and AIDS continues to evolve. Treatment options are improving allowing individuals with HIV to live comfortably. And every day researchers work to develop a vaccine that will provide significant protection for individuals who may be exposed to the virus. This post is a short overview of the history and current state of HIV vaccine research. If you’re interested in learning more about the history of HIV vaccine development, please visit the NIAID’s website dedicated to HIV/AIDS research and be sure to read through their ‘History of HIV Vaccine Research’ timeline which includes brief information about other previous clinical trials not discussed in this article. Or click the links embedded in this article to learn more about the specific clinical trials and their results.

References:

“Experimental MRNA HIV Vaccine Safe, Shows Promise in Animals.” National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9 Dec. 2021, www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/experimental-mrna-hiv-vaccine-safe-shows-promise-animals.

“Global HIV and AIDS Statistics-Fact Sheet.” UNAIDS, www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 20 Dec. 2021.

“History of HIV Vaccine Research.” NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 22 Oct. 2018, www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/hiv-vaccine-research-history.

“HIV Vaccine Development.” NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 15 May 2019, www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/hiv-vaccine-development.

“NIH and Partners Launch HIV Vaccine Efficacy Study.” NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 30 Nov. 2017, www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/nih-and-partners-launch-hiv-vaccine-efficacy-study.

“NIH and Partners to Launch HIV Vaccine Efficacy Trial in the Americas and Europe.” NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 15 July 2019, www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/nih-and-partners-launch-hiv-vaccine-efficacy-trial-americas-and-europe.