Health care personnel have assisted military units for centuries, both in unofficial capacities and as recognized members of the armed forces. Whether they were actively treating injured soldiers on the frontline or performing complex surgeries in military hospitals, physicians, surgeons, nurses and other health professionals worked alongside soldiers and commanders to ensure that the injured were properly treated.

Prior to the 19th and 20th centuries, healthcare treatment within the military was largely decentralized and relied on inaccurate information on wound treatment and patient care management. But as more advanced weapons and military tactics were introduced, countries and military leaders invested in their healthcare infrastructure which led to lower mortality rates and the decrease of widespread infection within military camps. Many of the inventions introduced during conflicts such as the Napoleonic Wars, the American Civil War and the World Wars have been carefully refined and serve as the foundation for today’s current military medicine practices.

Health and medicine have been the focus of research for centuries. Many ancient historical figures and civilizations documented their theories about human anatomy, physiology, the nature of diseases and health remedies. Preserved historical texts from ancient civilizations provide us with a glimpse of some of the health treatments and theories proposed by scholars. In Homer’s The Iliad, surgeons were portrayed as “skilled and professional physicians who expertly treated wartime trauma.” (Manring et al., 2009, pg. 2173) Ancient Egyptians and Babylonian-Assyrians left behind texts and treatises that showed cultures with sophisticated and thoughtful ideas about medicine and the human body. (Van Way, 2016)

During the time of the Roman Empire, “The Roman army had organized field sanitation, well-designed camps, and separate companies of what we would now call field engineers. They had a much better grasp of sanitation and supply than anyone else before, or for a long while.” (Van Way, 2016, pg. 260) While ancient civilizations lacked the technology and scientific theories that form the foundation of modern medicine, these cultures worked to protect their injured soldiers during battle. Some civilizations, such as the Romans, understood the importance of maintaining clean environments to prevent epidemics from debilitating their armed forces. As Dr. Charles Van Way III wrote, “Because of their [The Romans] improved sanitation, their armies suffered somewhat less from the epidemics which swept military camps, but only by comparison with their opponents.” (Van Way, 2016, pg. 261)

Unfortunately, when the Roman Empire fell, their ideas on sanitation and healthcare management were lost. For years, there were few scientific advances and many physicians relied on the ancient and incorrect humoral theory or four humors theory which was first suggested by the Ancient Greeks. According to this theory, the human body consisted of four ‘humors’: black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm. If a person was ill, humoral theorists believed the sickness was caused by an imbalance of humors within the body, instead of pathogens or forces outside the body. While there are some critics of this theory, it was the prevailing medical belief until the 18th and 19th centuries.

With the development of the scientific method around the 17th century, empirical observations became the basis for theories; the humoral theory eventually fell out of favor and more evidence-based practices/theories took its place. This impacted military medicine as healthcare responders developed new techniques that contributed to declining mortality rates and a more sanitary wound treatment management system.

Some discoveries and resources that were developed during this time include Jean Louis Petit’s tourniquet, Pierre-Joseph Desault’s description of the debridement of wounds and the publication of three textbooks on military medicine. (Van Way, 2016, pg. 262) But it was during the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) where military medicine began to improve and leaders recognized the importance of a well maintained military healthcare system. Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey is seen as the originator of modern military medicine. Some of his contributions to the field include an early framework for the triage system, the “ambulance volante” or flying ambulance and the use of field hospitals that were located away from the battlefield. (Van Way, 2016; Manring et al., 2009)

Despite the recommendations created by Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, armies still failed to create an organized healthcare system within their military. This caused controversy during some campaigns. For example, during the American Civil War (1861-1865) both the Union and Confederate armies “had physicians, but there was only a rudimentary hospital and evacuation system…Public health was terrible. Many soldiers died of disease, often even before reaching the battlefield.” (Van Way, 2016, pg. 336) This eventually led to the establishment of a military medical corps that treated the injured soldiers. And during the Crimean War (1853-1856), public outrage over the treatment of wounded British soldiers led the War Office to enlist the services of Florence Nightingale. Nightingale and her staff of volunteers focused on sanitation, ventilation and waste disposal. Because of her efforts, she “broke the monopoly of health care as the sole providence of the physician, which led to the development of the healthcare team in modern medical practice.” (Manring et al., 2009, pg. 2169)

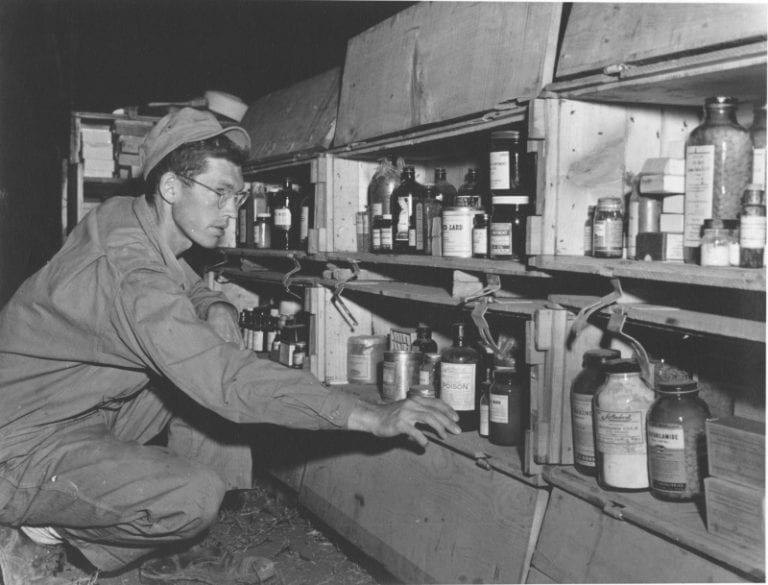

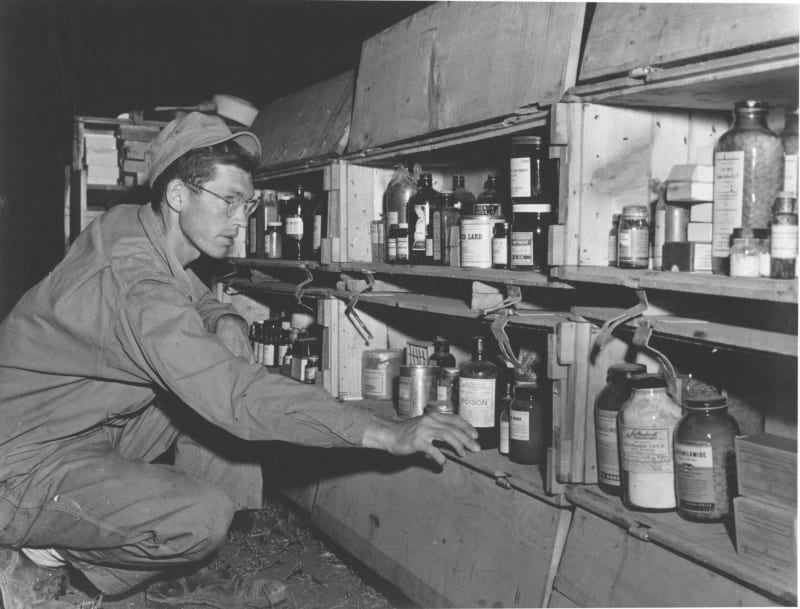

Military medicine faced its greatest challenge during the world wars and the field continued to shape itself into the modern version that is present today. When the U.S. joined World War I (1914-1918), hospitals, doctors, nurses and ambulances accompanied the soldiers and commanders. Ambulances were used to transport the wounded from the battlefield, and from there the soldiers would be taken to a healthcare team or moved to a facility where they could recover. (Van Way, 2016) Between the wars, medical advancements were incorporated in the field of military medicine such as “Blood and plasma transfusions, widespread use of intravenous fluids, antibiotics (but limited to penicillin and sulfonamides), endotracheal intubation, thoracic and vascular surgery, and the care of burn wounds.” (Van Way, 2016, pg. 338)

Military medicine was further tested during conflicts such as the Korean War (1950-1953), the Vietnam War (1955-1975), the Gulf War (1990-1991) and the wars in Afghanistan (2001-2021) and Iraq (2003-2011). According to Manring et al’s 2009 historical review, “Trauma care for US soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan currently is provided through five levels of care: Level I, front line first aid; Level II, FST (Forward Surgical Team); Level III, CSH, which is similar to civilian trauma centers; Level IV, surgical hospitals outside the combat zone…and Level V, major US military hospitals…” (Manring et al., 2009, pg. 2171)

The path to our current military medicine field and system was windy. The field was influenced by scientific advances and historical figures such as Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, Florence Nightingale, Dr. Walter Reed, Leonard Wood and thousands of physicians, surgeons, nurses, ambulance drivers and other professionals. If you are interested in hearing firsthand accounts from military healthcare professionals, visit the Library of Congress’ collection ‘Healing with Honor: Medical Personnel.’ The collection features personal narratives from people who served in conflicts such as World War I, the Korean War or the war in Afghanistan. ‘Healing with Honor: Medical Personnel’ is an excellent way to learn more about the field of military medicine and its commitment to the treatment of soldiers harmed during conflicts.

References:

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, October 5). Leonard Wood. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leonard-Wood

- Fauntleroy, A.M. (1916). The Surgical Lessons of the European War. Annals of Surgery, 64(2), 136-150.

- Lange, K. (2021). Walter Reed: Get to Know the Man Behind the Medical Center. U.S. Department of Defense. https://www.defense.gov/News/Inside-DOD/Blog/Article/2494459/walter-reed-get-to-know-the-man-behind-the-medical-center/

- Manring, M.M., Hawk, A., Calhoun, J.H., & Anderson, R.C. (2009). Treatment of War Wounds: A Historical Review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 467(8), 2168-2191.

- Underwood, E. Ashworth (2023, March 31). Walter Reed. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Walter-Reed

- Van Way III, C. (2016). War and Trauma: A History of Military Medicine. Missouri Medicine, 113(4), 260–263.

- Van Way III, C. (2016). War and Trauma: A History of Military Medicine-Part II. Missouri Medicine, 113(5), 336-340.

- Walter Reed (1851-1902). (2023). PBS.org. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/fever-walter-reed/

- Wintermute, B.A. (2011). Public Health and the U.S. military: a history of the Army Medical Department, 1818-1917. Routledge.