In honor of National Hispanic Heritage Month, let’s spend some time focusing on SALUD!

SALUD is a student-run organization at GW which was founded about five years ago, and is dedicated to teaching and learning Medical Spanish. During the academic year, SALUD runs regular Spanish classes for medical students at three different levels: Beginner, Intermediate, and Advanced. The content of these sessions, which occur during the lunch hour, is keyed to vocabulary related to body systems students are covering in the Practice of Medicine course.

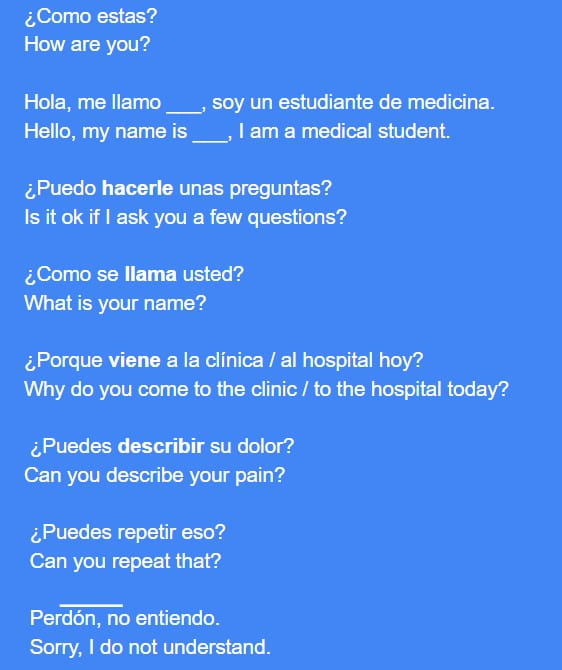

In class one day in early Fall, MS2 student instructors Emily and Giuliana ask the eight students attending the Advanced level class where they have learned their Spanish. Some speak it at home, while others have studied the language. There is a review of the vocabulary for the musculoskeletal system, after which the students partner up to practice patient interview skills. “¿Que le molesta?” (“Can you tell me what hurts?”) is one opening, whereas others might start with, “¿Necesita un intérprete?” (“Do you need an interpreter?”) Some students form groups of three, with one student acting as the interpreter. A student is curious about interpreting opportunities. While certification is required to be a medical interpreter, GW students are able to volunteer and use their language skills as patient navigators at the GW Healing Clinic, where about 80% of the clientele are Spanish-speaking.

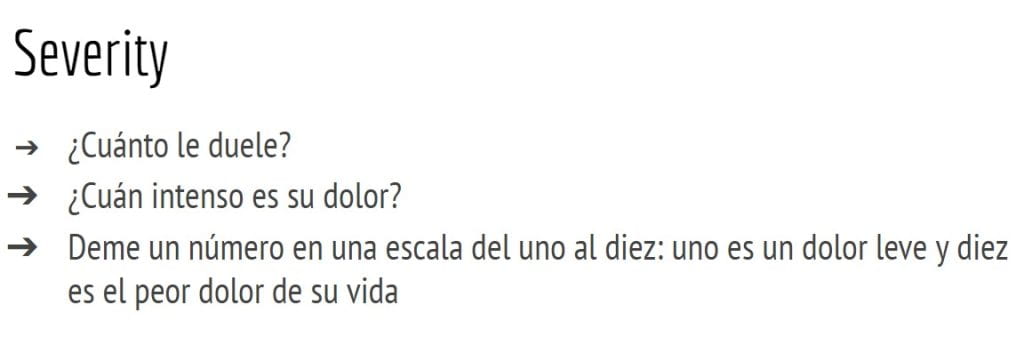

Over in the Intermediate level classroom, students are reviewing musculoskeletal vocabulary, translating it from Spanish to English. The lesson follows the structure of a history of present illness, teaching students to seek information from patients on the location, quality, and severity of their pain, along with its duration, timing and context. The instructor points out synonyms, such as débil and tenue for weak, as well as words that have more than one meaning, like sordo, which can mean deaf, but also dull, which might describe a patient’s pain. In the Beginner classroom, a dozen students begin their exploration of the same vocabulary at a slower pace.

In addition to teaching Medical Spanish, classes aim to teach students the correct use of interpreters. SALUD also serves the Latinx community in DC through Bridge to Care, an initiative of the GW Healing Clinic. Because up to 80% of patients seeking care at the Healing Clinic are Spanish-speaking, the support of students with Spanish-speaking skills from across the MD Program, PA Program, and MPH candidates from the Milken Institute of Public Health is essential.

A few days after the first lesson of the year, I met with two of SALUD’s board members, Tammy Moscovich (MS2) and Alisha Pershad (MS2). While Tammy was raised in a Spanish-speaking family, Alisha’s interest in learning Spanish developed through school. Alisha sought to put her Spanish skills to use, and pursued official interpreter training to earn a certification. Through her SALUD teaching, Alisha hopes “to empower others” to combine their Spanish-speaking skills with patient care.

The curriculum used by SALUD comes from a Medical Spanish course from Boston University, which was adapted with permission by medical student Cecilia Velarde De La Via (MS3). The curriculum correlates to the system blocks students learn about in the Practice of Medicine course, and includes both vocabulary, sample patient interviews, and flash card decks. The Intermediate level class is “more conversational than technical,” according to Tammy, whereas the Advanced class focuses more on review.

Are there SALUD success stories? Tammy and Alisha shared one: a current MS3 student who began Medical Spanish last year eager to practice her skills gained confidence through the classes. Now, in rotations, she feels more confident with her Spanish skills in working with patients. For Tammy, her time serving at Bridge to Care serves as a good refresher for vocabulary lessons. Then there are the finer points to learn when working with patients coming from different parts of the Spanish-speaking world, like the difference in terminology from one country to another, or learning the informal terms used by patients in a medical context, versus the clinical terms. Tammy commented that, “This is the word I use” is a valuable contribution to the Spanish lessons, helping to communicate the variations across borders. Alisha agrees, adding that classes are enriched by people bringing their individual experiences and sharing it.

The increased arrival of migrants to the DC area is something the GW Healing Clinic is experiencing via some of the patients coming through its doors. Alisha reported that there have been more patients arriving with acute conditions, adding that “it’s gratifying to facilitate the encounter, and help them recover.”

From the classroom to the exam room, SALUD is helping students increase their confidence in both bilingual encounters and collaborating with interpreters, while helping patients in the community access medical care that speaks their language.