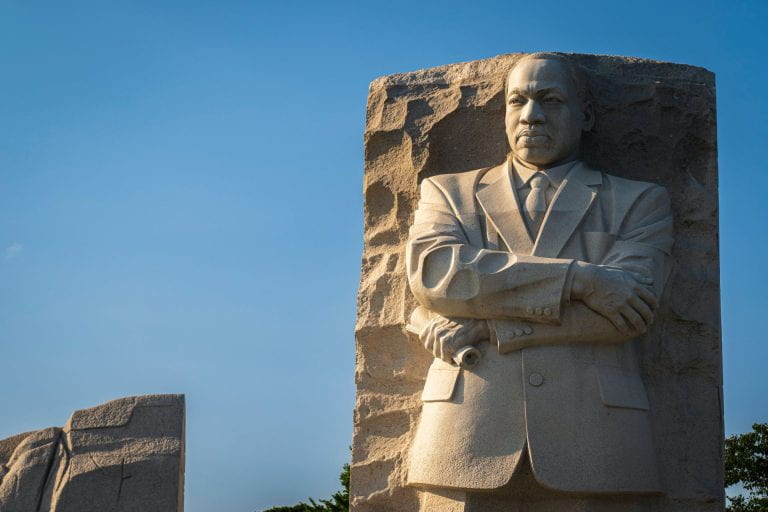

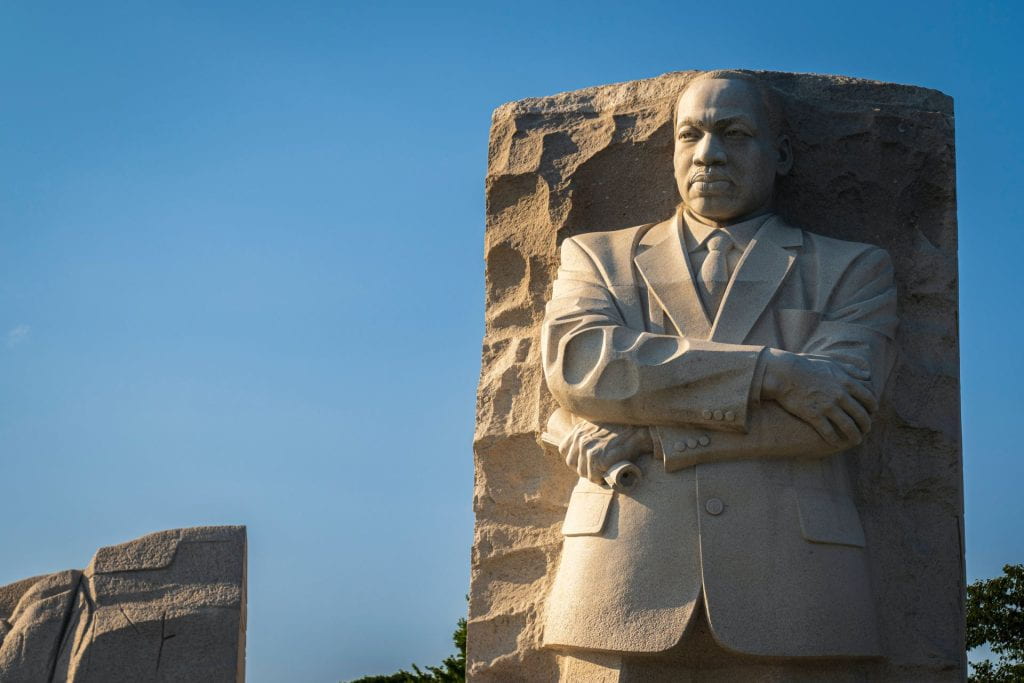

As we reflect on the life, work, and impact that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. has had on our nation and the world, we are reminded that Dr. King was passionate about activism on racial discrimination, poverty, and health disparities. A great way to honor Dr. King’s legacy and continue his important work is to learn more about anti-racism, inequities, and disparities in healthcare and use this knowledge to help build a more inclusive healthcare system. Himmelfarb Library has some great resources that can help you learn more about these topics so you can put your knowledge into action!

Himmelfarb Resources:

Himmelfarb’s Anriracism in Healthcare Guide provides information and resources related to antiracism in healthcare including links to professional healthcare organizations centered around diversity and health justice issues, training resources, and links to GW-specific organizations. Browse the Journal Special Collections tab to find journal issues and health news on antiracism-related issues. Antiracism books and ebooks available at Himmelfarb are also included in this guide including:

- Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism by John Hoberman

- Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional by Chandra Ford, Derek Griffith, Marino Bruce, and Keon Gilbert

- Under the Skin: Racism, Inequality, and the Health of a Nation by Linda Villarosa

- Medical Bondage: Race, Gender and the Origins of American Gynecology by Deidre Cooper Ownes

- Eliminating Race-Based Mental Health Disparities by Monnica Williams, Daniel Rosen, Jonathan Kanter, and Patricia Arredondo

- Health Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Context, Conversations, and Solutions by Patti Renee Rose

The Antiracism in Healthcare Guide also has links to podcasts, tutorials, and videos including:

- Beyond the White Coat: Do No Harm - Racism in Patient Care (Podcast episode)

- Words Matter: An Anti-bias Workshop for Health Care Professionals to Reduce Stigmatizing Language (Self-Guided Tutorial)

- Dismantling Racism Works Web Workbook (Tutorial)

- The Healthcare Divide (Video)

- Racial Equity Playlist from the American Public Health Association (Video playlist)

In addition to the Antiracism in Healthcare Guide, Himmelfarb has a Diversity and Disparities in Health Care collection of books and e-books with nearly 200 books addressing issues of disparity and representation of minority communities in healthcare.

Advancing the Dream Event:

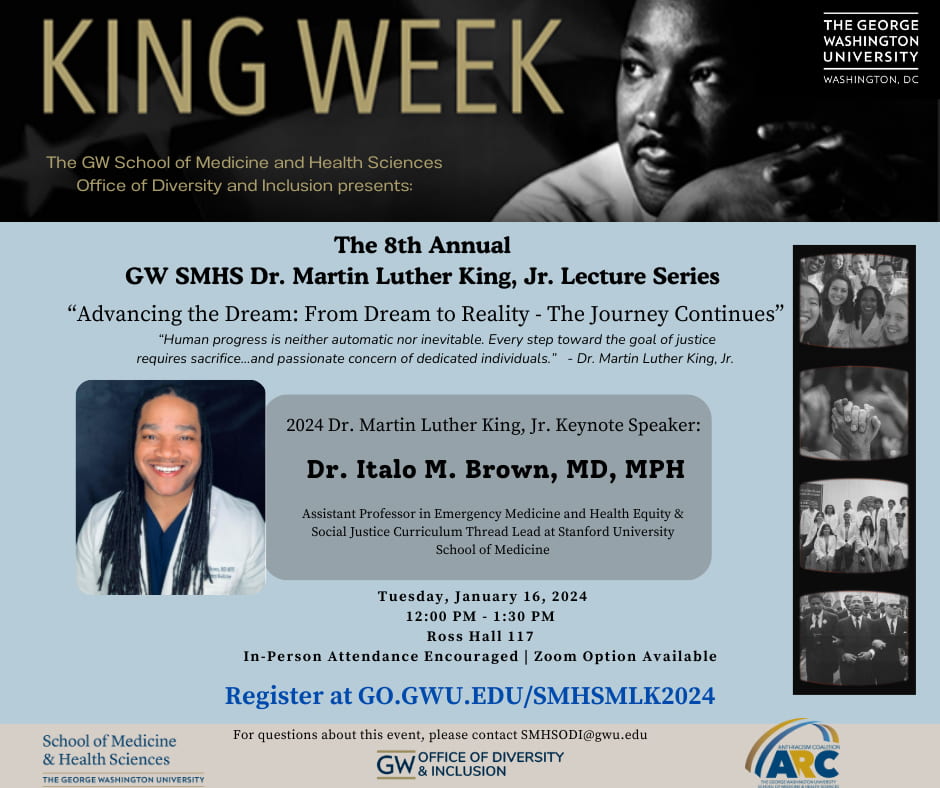

On Tuesday, January 16, 2024, at Noon, SMHS and the Anti-Racism Coalition will hold the 8th Annual SMHS Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Lecture Series - Advancing the Dream: From Dream to Reality - The Journey Continues. This year’s speaker is Dr. Italo M. Brown, MD, MPH. Dr. Brown is an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Health Equity and Social Justice Curriculum Thread Lead at Stanford University School of Medicine. Please join us in room 117 of Ross Hall (virtual attendance via Zoom is available) for this great event!

Student and Professional Organizations:

If you are interested in becoming more involved, consider reaching out to local student or professional organizations such as White Coats for Black Lives or the Antiracism Nursing Student Alliance. Involvement with these and similar organizations can help you put your knowledge into action and offer opportunities for collaboration in furthering the cause of finding solutions to healthcare disparities and opportunities to educate others on issues of health injustices.