Beethoven, one of the great musical geniuses of the 19th century, was deaf when he wrote some of his best known works. He had progressive hearing loss starting in his 20’s and was functionally deaf during his late period when he wrote his most expressive and innovative sonatas, string quartets, and the Ninth Symphony (Ode to Joy). Beethoven also suffered from gastrointestinal symptoms most of his adult life and died of liver failure. In 1802, he requested that his medical conditions be disclosed to the public after his death in a letter to his brothers known as the Heiligenstadt Testament.

Historians and musicologists have speculated if he had a heritable disorder or infectious disease that contributed to his hearing loss and death. Alcoholism was suspected as a factor in his liver disease. There was a family history of alcohol dependence and some of his associates claimed he drank heavily, though others said he did not drink more than was typical at that time.

Recent advances in ancient DNA methods presented an opportunity to learn more about Beethoven’s medical conditions. A team of 32 international researchers used eight surviving locks of Beethoven’s hair for their analysis. Several locks were taken by friends when Beethoven died in 1827 and others were given to friends and associates while he was alive. Over the years they were sold and passed down to others and the provenance of some were questionable. The locks were analyzed in this new study to determine their authenticity, using a novel geo-genetic triangulation technique. Additionally, the researchers “analyzed Beethoven’s genome for genetic causes of and risk for somatic disorders in addition to metagenomic screening for evidence of infections, followed by targeted DNA capture.” (Begg, et al, 2023)

Five of the locks were determined to originate from a single individual or monozygotic twins and had damage patterns that authenticated them for early 19th century origin. A non-matching lock called the Hiller lock was used in previous genetic and forensic testing featured in the book and movie, Beethoven’s Hair. It was found to be from a woman, invalidating results indicating lead poisoning as a contributor to Beethoven’s hearing loss and other maladies.

Analysis on the Y chromosome revealed a surprise finding. Five living men from the Beethoven patrilineage had a common ancestor in Aert van Beethoven (1535-1609). But their Y chromosomes did not match with any of the five authenticated Beethoven hair samples. The researchers conclude that there was at least one extra pair paternity event in Beethoven’s ancestry. Further analysis of descendants of Beethoven’s brother Karl leaves open the possibility that the two may have been half brothers.

Beethoven’s GI symptoms were consistent with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. His hearing loss could have been associated. Other possible related causes for the hearing loss were otosclerosis, sarcoidosis or systemic lupus erythematosus. A genome wide association study eliminated most of these as possibilities, except for lupus where there was some elevated polygenic risk.

Celiac disease and lactose intolerance were both eliminated as possible causes of his gastrointestinal symptoms through testing for associated alleles. He actually had some elevated genetic protections against irritable bowel syndrome, making it also unlikely.

They analyzed 55 genes where variants could cause monogenic post-lingual hearing loss and 209 related to pre-lingual hearing loss. There were no positive findings.

In summary, we could not reliably evaluate most hypothesized multifactorial causes of Beethoven’s hearing loss, nor did we identify a monogenic origin.”

(Begg, et al, 2023)

Beethoven’s polygenic risk for liver cirrhosis was found to be elevated in his PNPLA3 gene and his HFE gene. This combined with heavy drinking could have caused his liver failure. Additionally, hepatitis B DNA was found in the Stumpff Lock hair which was the best preserved sample. Researchers could not tell how long he’d had the hepatitis B infection. The positive lock was taken at his death and represented the final months of his life. Tristan Begg, the lead author of the study, wrote more about the possible role of hepatitis B in Beethoven’s liver failure on William Meredith’s blog. Meredith is a Beethoven scholar who participated in the genome study.

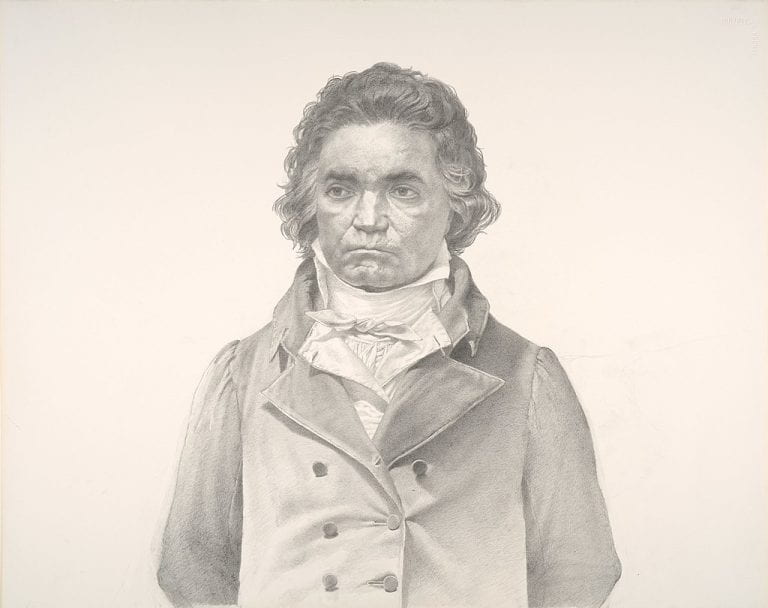

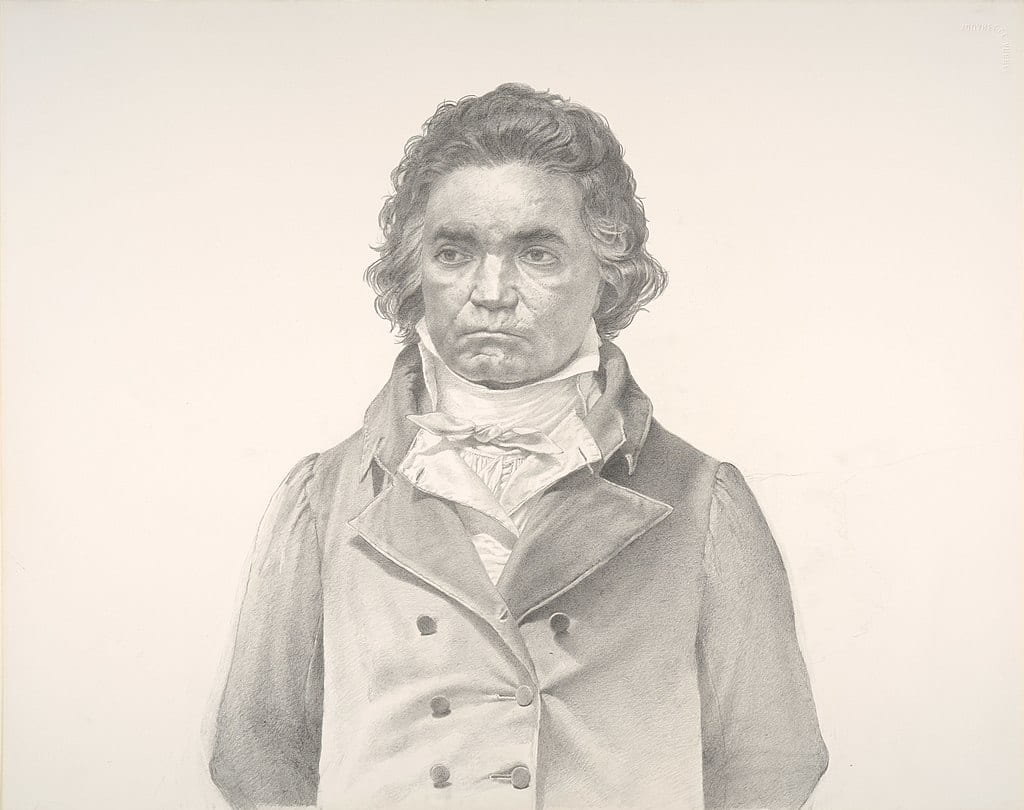

Though not addressed directly in the paper, the study brings to an end the theory that Beethoven was black. Noting the similarities in their appearance, the bi-racial composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was the first to raise the possibility. Many contemporaries of Beethoven described him as dark, brown or ruddy in complexion and noted his broad, rounded nose which can be seen in his life mask taken in 1812. The idea has persisted since Coleridge-Taylor introduced it, and was repeated by Malcolm X and a 1969 Rolling Stones article titled “Beethoven was black and proud!” More recently it was the subject of scholarly articles and even a Twitter meme. This genomic analysis confirms that Beethoven’s ancestry was greater than 99% European, with the strongest autosomal match with present day North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany.

Although there was no definitive finding on Beethoven’s hearing loss, there was plenty to advance the existing knowledge base and establish leads for future research. The study demonstrates how much can be learned from a few strands of centuries old hair through new genetic analysis tools.

References

Begg TJA, Schmidt A, Kocher A, et al. Genomic analyses of hair from Ludwig van Beethoven. Curr Biol. 2023 Apr 24;33(8):1431-1447.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.041. Epub 2023 Mar 22. PMID: 36958333.

Clark P. ‘Beethoven was black’: why the radical idea still has power today. The Guardian. 7 Sep 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/sep/07/beethoven-was-black-why-the-radical-idea-still-has-power-today