In an effort to remain accountable to communities who have been negatively impacted by past and present medical injustices, the staff at Himmelfarb Library is committed to the work of maintaining an anti-discriminatory practice. We will uplift and highlight diverse stories throughout the year, and not shy away from difficult conversations necessary for health sciences education. To help fulfill this mission, today's blog post highlights transgender healthcare equity.

Visibility. What does it mean to you? Does it mean being seen or acknowledged? If something or someone is visible are they not only ‘seen’, but also understood? When someone is seen, is it the individual that is seen or is it a label ascribed to them that is seen? A fuller understanding of what it means to be transgender and the issues transgender people face within the current healthcare climate is the first step in changing the system towards a more equitable healthcare system for transgender people.

On March 31, 2022, International Transgender Day of Visibility, the United States is set to to break its all-time record for the introduction of anti-transgender legislation. While anti-transgender legislation covers a vast array of human activities – from using the restroom to participating in sports – the impact this kind of legislation has or may have on healthcare is not something to be ignored. Around the United States, transgender people, their families, and their healthcare providers are at risk of severe punishment for trans-affirming care.

In Texas, transgender rights came into the spotlight recently when Gov. Greg Abbott instructed health-related agencies in the State of Texas to treat gender-affirming care provided to transgender minors as “child abuse” and that anyone could and should report transgender individuals, their families, and their healthcare providers under that definition (Ghorayshi, 2022; Goodman, 2022). Despite having no legally binding authority and being temporarily blocked by Judge Amy Clark Meachum, this order has already forced many families to face investigations that threaten to separate them from their transgender children. (Klibanoff & Dey, 2022)

In Idaho, HB675 seeks to group a variety of medical procedures under the definition of “genital mutilation” and was introduced in late February. Should this bill pass, medical service providers who administer medications or procedures in order “to change or affirm the child's perception of the child's sex if that perception is inconsistent with the child's biological sex, shall be guilty of a felony” (H.B. 675, 2022). This excludes procedures such as circumcision and controversial and often medically unnecessary surgeries performed on intersex children (Ejiogu, 2020), but includes the use of puberty blockers (also known as GnRHas) to delay puberty until a child comes of age and has the ability to consent to hormone replacement therapy if they so choose. A healthcare provider convicted of a felony under this proposed legislation would “be imprisoned in the state prison for a term of not more than life” (H.B. 675, 2022). This bill passed the House, but the Idaho Senate Majority Caucus released a statement against HB675, so it is unlikely that it will become law (Russell, 2022).

In Louisiana, bill HB570 functions similarly to Idaho’s HB675, with a few slight changes. Rather than a felony charge, healthcare providers would “be subject to discipline by the licensing entity with jurisdiction over the physician, mental health provider, or other medical healthcare professional” (H.B. 570, 2022). Healthcare providers might also be liable for compensation should the patient file a claim, or should their parents do so in the patient’s stead. In addition, HB570 includes sections that would restrict usage of public funds that might be used for gender affirming care (H.B. 570, 2022). This bill is currently awaiting review by the Louisiana House Committee on Health and Welfare.

In Tennessee, bill HB2835 is similarly structured. This bill includes restrictions regarding public fund usage, but medical service providers would be “subject to revocation of licensure and other appropriate discipline by the medical professional's licensing authority. The medical professional will be subject to a civil penalty of up to $1,000 per occurrence” (H.B. 2835, 2022). HB2835 also includes provisions that would require any individuals employed by the state to “immediately notify, in writing, each of the minor's parents, guardians, or custodians” of a minor’s transgender identity upon learning of it (H.B. 2835, 2022). The bill does not include any exceptions regarding this requirement should there be reason to believe that the parents, guardians, or custodians would react to the news violently. TN HB2835 was moved to the Tennessee House Health Committee for review on March 22, but was taken off notice and is unlikely to continue through any future voting procedures. (H.B. 2835, 2022)

These are only a few of the many parallel legislations raised in the last few months that have framed transgender-related care as abuse and mutilation. New Hampshire, Arizona, and Wisconsin have seen similar legislative proposals. That said, regardless of whether or not this kind of proposed legislation is passed, they raise a startling concern: how can healthcare providers care for their transgender patients should state laws subject those involved to harsh punishments?

The truth is that visibility alone does not protect transgender individuals who would be impacted by such legislation. Healthcare providers can update their knowledge regarding legislation that targets gender affirming care. Freedomforallamericans.org features up to date information on all current anti-transgender bills, many of which are healthcare related. The Transgender Law Center’s National Equality map tracks legislation that impacts LGBTQIA+ individuals and includes healthcare as one of the major legislative categories.

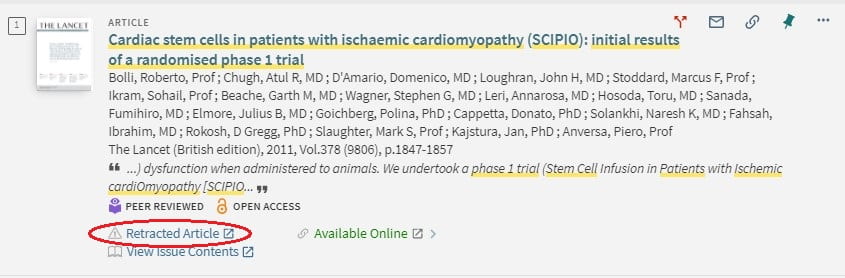

Healthcare providers can access resources to update their knowledge and to support high-quality care for transgender individuals via multiple resources available in Himmelfarb Library’s collections including:

- Keuroghlian, A. S., Potter, J., & Reisner, S. L. (2022). Transgender and gender diverse health care : the Fenway guide. McGraw Hill.

- LGBTQ+ : support and care. Part 3, Caring for transgender children (2021). American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Ferrando, C. A. (2020). Comprehensive care of the transgender patient. Elsevier.

- Forcier, M., Van Schalkwyk, G., & Turban, J. L. (2020). Pediatric gender identity : gender-affirming care for transgender & gender diverse youth. Springer.

- Hardacker, C., Ducheny, K., & Houlberg, M. (2019). Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Health and Aging. Springer. Himmelfarb Library Book Stacks: Book Stacks HQ77.9 .T73 2019

The Whitman Walker clinic has a Cultural Competency toolkit that focuses on practices you can provide to all LGBTQIA+ patients. Other helpful associations include:

- The DC Center for the LGBTQ Community aims “to promote health equity in our local LGBTQ Community'' with programs such as free at-home STI & HIV testing kits, the binder donation project, trauma-informed mental health support groups, and more.

- The DC Trans Coalition “is a volunteer, grassroots, community-based organization dedicated to fighting for human rights, dignity, and liberation for transgender, transsexual, and gender-diverse (hereafter: trans) people in the District of Columbia.” (“About DCTC”) The DC Trans Coalition has a transgender healthcare resource list, as well as a guide to educate transgender DC residents on their rights.

- The Fenway Institute has a sub-organization known as The National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center, which focuses on producing seminars and guides to educate health service providers. These resources cover gender-affirming surgeries, HIV and PrEP, research and data collection, and more.

Nationally, transgender individuals can find healthcare-related support through a variety of organizations. Healthcare providers can share the following resources with their transgender patients in order to improve patient education, particularly since generalized healthcare is often not suitable for transgender individuals:

- The National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) aims “to change policies and society to increase understanding and acceptance of transgender people,” by way of legal support, news involving transgender rights, and guides for a variety of transgender-related topics”. (“About Us”, transequality.org) The topics of those transgender-specific guides include general healthcare, COVID-19, and health coverage. NCTE also has a page dedicated to mutual aid and emergency funds in the event that a transgender individual needs legal support when facing discrimination in a variety of spheres of life, including healthcare.

- In addition to legal support in defense of transgender individuals facing discrimination, Lambda Legal, which boasts “the oldest and largest national legal organization whose mission is to achieve full recognition of the civil rights of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people and everyone living with HIV” (“About Us”, Lambda Legal) has a downloadable Transgender Rights Toolkit to support transgender individuals facing any number of discriminatory matters, including health care discrimination. Lambda Legal also has a LGBT rights by state tool to help find information about local legislation, including healthcare-related legislation.

- The Transgender Law Center (TLC), a trans-led advocacy organization, hosts a page of health resources. This includes a guide for transgender patients on how to negotiate for more inclusive coverage, as well as a guide that explains nondiscrimination rights under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

- The Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund, which offers legal services and public policy education, also manages the Trans Health Project. This program includes insurance tutorials, statements from major medical organizations in recognition of the medical necessity of treatments for gender dysphoria, literature reviews to support appeals that require proof of medical necessity, and more.

- Anti-transgender discrimination can also be reported through the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which has a page dedicated to transgender health. This page regularly updates with press releases and news analyses.

Visibility is important, and at Himmelfarb we believe that it is a human right to be acknowledged for who you are. While transgender healthcare has come a long way, there are still ways that we can improve our care and protect our patients, particularly those who live in states with anti-transgender legislation on the rise. We hope that the resources in this piece will help medical professionals, transgender patients, and allies to take action and defend transgender people so that they can be visible.

References

“About DCTC.” DC Trans Coalition. https://dctranscoalition.wordpress.com/about-dctc/. Accessed March 30, 2022.

“About Us.” Lambda Legal. https://www.lambdalegal.org/about-us. Accessed March 30, 2022.

“About Us.” National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/about. Accessed March 30, 2022.

Ejiogu, N. I. (2020). Conscientious Objection, Intersex Surgeries, and a Call for Perioperative Justice. Anesthesia and analgesia. Vol. 131 (5), 1626-1628. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004946

Feinberg, L. (2013). Transgender liberation: A movement whose time has come (pp. 221-236). Routledge.

Ferrando, C. A. (2020). Comprehensive care of the transgender patient. Elsevier.

Forcier, M., Van Schalkwyk, G., & Turban, J. L. (2020). Pediatric gender identity : gender-affirming care for transgender & gender diverse youth. Springer.

Ghorayshi, A. (2022, February 23). Texas Governor Pushes to Investigate Medical Treatments for Trans Youth as ‘Child Abuse’. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/23/science/texas-abbott-transgender-child-abuse.html

Goodman, J. D. (2022, March 11). How Medical Care for Transgender Youth Became ‘Child Abuse’ in Texas. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/11/us/texas-transgender-youth-medical-care-abuse.html

Hardacker, C., Ducheny, K., & Houlberg, M. (2019). Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Health and Aging. Springer.

H.B. 570, House of Representatives, 2022 Reg. Sess. 397. (Louisiana 2022). https://www.legis.la.gov/legis/ViewDocument.aspx?d=1256678

H.B. 675, House of Representatives, 2022 2nd Reg. Sess. (Idaho 2022). https://legislature.idaho.gov/sessioninfo/billbookmark/?yr=2022&bn=H0675

H.B. 2835, House of Representatives, 2022 Health Subcommittee. (Tennessee 2022). https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/Billinfo/default.aspx?BillNumber=HB2835&ga=112

Keuroghlian, A. S., Potter, J., & Reisner, S. L. (2022). Transgender and gender diverse health care : the Fenway guide. McGraw Hill.

Klibanoff, E., & Dey, S. (2022, March 11). Judge temporarily blocks Texas investigations into families of trans kids. Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2022/03/11/transgender-texas-court-hearing/

LGBTQ+ : support and care. Part 3, Caring for transgender children (2021). American Academy of Pediatrics.

Russell, B. (2022, March 15). Senate GOP releases statement on its opposition to HB 675 on trans youth care. Idaho Press. https://www.idahopress.com/eyeonboise/senate-gop-releases-statement-on-its-opposition-to-hb-675-on-trans-youth-care/article_5c5305d4-9854-568f-b27a-76865a04b75c.html