Washington D.C. has been home to many influential and powerful women. Whether they were born in the city or moved to the capital during the course of their lives, many women who helped shape the country lived in and formed communities in D.C. The stories of the following three women provide a glimpse into the ways in which women contributed to the well-being of the city and the broader country!

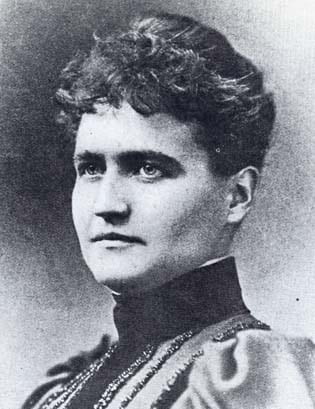

Charlotte Dupuy:

Born on the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Rachel and George Stanley, Charlotte Dupuy (nee Stanley) was an enslaved woman who petitioned the U.S. Circuit Court of the District of Columbia for her freedom. When Charlotte was a child, she, her mother and two siblings were enslaved to Daniel Parker of Dorchester County, Maryland. While Charlotte’s father was able to eventually secure freedom for his wife and two children, for unknown reasons, Charlotte was still enslaved to the Parker household. At the age of nine, Charlotte was then sold to James Condon, a local tradesman. While working for this new household, Charlotte maintained contact with her own family, but several years later, Condon moved his family from Maryland to Lexington, Kentucky, separating Charlotte from her relatives.

While living in Lexington, Charlotte eventually met and married Aaron Dupuy, an enslaved man who worked at Ashland, the estate for Whig politician Henry Clay. After Charlotte and Aaron’s marriage, Henry Clay purchased Charlotte and she worked as a domestic servant for the Clay estate. Clay was a politician, serving in the House of Representatives in 1810 before becoming the Speaker of the House in 1817 or 1818. Clay moved his household, including Charlotte, Aaron Dupuy and their two children, to Washington D.C. When Henry Clay was appointed to the Secretary of State for the Adams administration, he once again moved his family, this time settling in the house across from the White House, now known as the Decatur House. While living in Washington D.C., Charlotte Dupuy was able to frequently visit her extended family and when Henry Clay sought to return to Kentucky years later, Charlotte resisted. A local lawyer filed a petition on Charlotte’s behalf as she attempted to seek her freedom through legal action. Charlotte Dupuy was one of many enslaved people who petitioned the courts and attempted to use legal precedents to gain their freedom. In Charlotte’s case, she argued that because her grandmother and mother were both free women, this entitled Charlotte to her freedom as well.

Unfortunately, the Circuit Court ruled against Charlotte and while she resisted returning to Henry Clay’s estate, she eventually was transported to New Orleans where she worked for Clay’s daughter. Charlotte Dupuy and her daughter gained their freedom in 1840 and while records are sparse, it seems likely that she continued to live in Kentucky to remain close to her husband and other children. Charlotte Dupuy’s story is a reminder of the ways in which enslaved people actively resisted their enslavement and her story is still told to modern day visitors of the Decatur House.

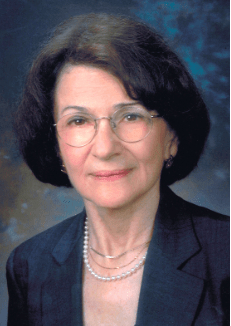

Eliza Scidmore:

This week the cherry blossom trees located on the Tidal Basin and around D.C. are predicted to hit peak bloom. There are countless people to thank for bringing cherry blossoms to Washington D.C. and one figure who was most influential in the beautification process was Eliza Scidmore!

Born in Iowa in 1856, Eliza Scidmore was an explorer, writer and editor who traveled through the Alaska Inside Passage and published the first Alaska travel guide which sparked tourism in the state. Scidmore also was a member of the National Geographic Society and sat on their Board of Managers. While she is remembered for her travel writing, one of her most lasting impacts is felt every spring when the cherry blossoms bloom.

During a visit to Japan, Scidmore was deeply impressed with the Japanese cherry trees and their flowers. When she returned to the United States, she immediately began to work to bring the trees to the States in an effort to beautify the Capital. Her efforts were initially rebuffed by the Superintendent of Public Buildings and Grounds. But this did not stop Scidmore. She eventually met and partnered with Department of Agriculture Plant Explorer David Fairchild who was actively engaged in his own work with the cherry blossoms. Scidmore also wrote a letter to First Lady Helen Taft who was also keen to improve the city. Scidmore’s original idea was to raise money to purchase a hundred trees each year for several years. But a Japanese chemist, Dr. Jokich Takamine, heard about Scidmore’s letter to First Lady Taft and this spiraled into multiple political and influential leaders working together to bring cherry blossom trees to the United States.

The Japanese government first donated a shipment of about 2,000 trees but unfortunately the trees were diseased and contained bugs that American scientists feared would be harmful to native plants. The first shipment of trees were burned as a result. The Japanese government then sent another shipment of 3,020 trees and once they were approved by scientists, the trees were planted around the Tidal Basin and throughout the city. Today, less than one hundred of these original trees are still on display. But the annual blooming of the cherry blossoms serves as a reminder of Eliza Scidmore’s dedication to beautifying Washington D.C.

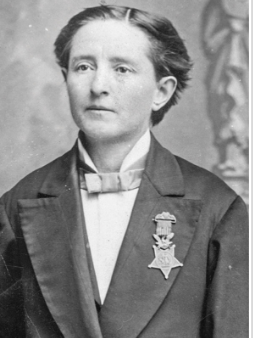

Mary Ann Shadd Cary:

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was a major figure in the women’s suffrage movement and spent years fighting for the expansion of voting rights.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was born in 1823 in Delaware to a family who actively participated in the Underground Railroad and assisted people who sought to claim their freedom. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, Mary Ann Shadd Cary and her family moved to Ontario, Canada. While living abroad, Cary opened her own schoolhouse where she taught both white and black children. She eventually married Thomas J. Cary and together they had two children.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Cary returned to the United States and assisted the war effort by recruiting soldiers to join the Union Army. When the war ended, she moved to Washington D.C. and enrolled in Howard University’s first law school cohort. She was politically active at this time; she wrote articles for the African-American newspaper, The New National Era and encouraged Black Americans to work together to recover after the end of slavery.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was passionate about voting rights. During the congressional committee meetings about the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Constitutional Amendments, Cary spoke before the House Judiciary Committee and encouraged congressional leaders to ratify the amendments. She was critical of the fact that the Fifteenth’s Amendment didn’t also extend voting rights to women, but she argued that voting rights should be granted to African-American men. Cary was a member of the National Woman Suffrage Association and continued to fight for the right for women to vote, hoping to one day see voting rights be given to women.

She lived in a brick row home located on W Street Northwest. The home is now a historic landmark, though it is not currently open to the public. A plaque outside the home shares a more detailed history about Mary Ann Shadd Cary and her efforts to uplift people within her community.

The Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum:

Charlotte Dupuy, Eliza Scidmore and Mary Ann Shadd Cary are just a few of the many women who lived in and left their mark on Washington D.C. Landmark plagues and historical sites share stories of other women such as suffragist Lucy Burns, entrepreneur Cathy Hughes, educator Mary McLeod Bethune and more. In a few years, Washington D.C. will also be home to the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum!

“With a digital-first mission and focus, the Smithsonian amplifies a diversity of women’s voices in a new museum and through the Smithsonian’s museums, research centers, cultural heritage affiliates, and anywhere people are online.” (About, n.d., para. 2) .

While the physical building is not projected to open until the 2030s or later, visitors can explore their digital exhibits, collections and collection items such as ‘In Her Words: Women’s Duty and Service in World War I’, ‘Women of Public Health’ and ‘American Women Athletes’. The Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum will be an essential resource for people interested in learning more about American Women’s History and the contributions women made to the United States.

There is a long history of women investing time and energy into improving Washington D.C. and the United States as a whole. If there is a local figure you’d like to highlight during Women’s History Month, we’d love to read about it in the comments!

References:

- About. (n.d.). Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://womenshistory.si.edu/about

- Eliza Scidmore. (2020). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://www.nps.gov/articles/eliza-scidmore.htm

- Eliza Scidmore’s Faithful Pursuit of a Dream. (2019). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://www.nps.gov/articles/scidmore.htm

- Jones, A.J. (n.d.). Stories/Charlotte Dupuy. Enslaved | Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade. https://enslaved.org/fullStory/16-23-126819/

- Mary Ann Shadd Cary. (2019). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://www.nps.gov/people/mary-ann-shadd-cary.htm