Pixabay, 2016

In an effort to remain accountable to communities who have been negatively impacted by past and present medical injustices, the staff at Himmelfarb Library is committed to the work of maintaining an anti-discriminatory practice. We will uplift and highlight diverse stories throughout the year, and not shy away from difficult conversations necessary for health sciences education. To help fulfill this mission, today's blog post highlights transgender healthcare equity.

Author notes

The topics presented in this article may be difficult and/or retraumatizing for some readers. Subject matter includes medical neglect, transphobic harassment, usage of slurs, medical misdiagnosis, death of a Black transgender women by medical neglect, and cancer.

While some of the sources cited in this article are from over a decade ago and may use outdated terminology and may misgender the individuals discussed in them, this article was written by a transgender member of Himmelfarb staff, who has used appropriate language in the article itself.

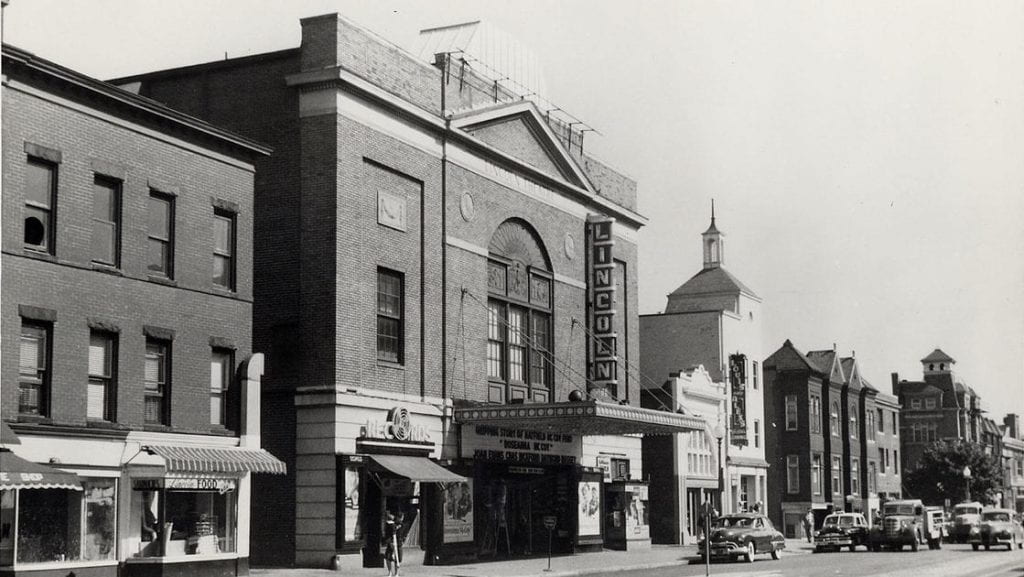

August 7th, 1995. Washington, DC.

A 24 year old woman named Tyra Hunter was critically wounded in a car accident when another driver ran a stop sign (Bowles, 1995). Once first responders came on the scene and assessed the situation, instead of treating her properly, they mocked and degraded her (Remembering Our Dead, 2019). When she was finally brought to the emergency room at DC General Hospital, she was given a paralytic and slowly bled out (Fox, 1998). The delay in treatment and degrading comments took place because she was a black transgender woman.

Tyra Hunter’s case is, perhaps, one of the more extreme instances of medical transphobia and healthcare inequity. That said, Tyra Hunter is one of many transgender people who have been victimized by anti-transgender prejudice – both personal and systemic – in healthcare.

From avoidance of medical care due to fear, to biased diagnoses from prejudiced professionals, to even the blatant transphobia that first responders directed at Tyra Hunter, transgender people – particularly for Black transgender women – frequently lack access to quality healthcare. In this post, we will review the most common ways prejudice and cultural incompetency impact transgender patients, and we will consider ways medical professionals can provide equitable healthcare to transgender individuals.

Medical transphobia can take many forms, and not all of them are as blatant as what Tyra Hunter experienced on the day of her death in 1995. Even microaggressions, when experienced over long periods of time, can cause transgender patients to avoid or delay seeking treatment. A study by Seelman et al. in the journal Transgender Health found that among transgender participants, “those reporting a noninclusive PCP or who delayed needed medical care because of fear of discrimination were less likely to have had a routine checkup in the past 2 years” (Seelman et al., 2017, p. 25). This is supported by a study by Jaffee et al., which found that “1 in 3 transgender respondents delayed needed medical care for an illness or injury due to discrimination” (Jaffee et al., 2016, p. 1012), and that “the odds of delaying needed care was approximately 4 times greater for those who reported having to teach their provider about transgender people” (Jaffee et al., 2016, p. 1012).

This fear of medical discrimination is by no means irrational. A study by Rodriguez et al. analyzing data from the National Transgender Discrimination Survey which included over 6000 participants, found that “more than one-third of transgender participants reporting having experienced discrimination in health-care settings” (Rodriguez et al., 2017, p. 980), wherein discrimination was defined as, “physical abuse, verbal harassment, and/or denied equal treatment” (Rodriguez et al., 2017, p. 975). Of note here is that this number parallels Jaffee et al.’s reported 1 in 3 transgender respondents delaying treatment.

Transgender patients’ lack of trust is also attributed to “Transgender Broken Arm Syndrome,” which occurs when healthcare providers attribute unrelated medical issues to a patient’s transgender identity or transition-related care. The colloquial term comes from the scenario where a transgender patient might go into the doctor for a broken arm, but the healthcare provider questions to the patient about their gender instead. Jennifer Kelley describes this kind of scenario with a patient named Cam in the article, Stigma and Human Rights: Transgender Discrimination and Its Influence on Patient Health. Cam wanted to see the doctor about a chronic issue unrelated to her transness, and perhaps discuss hormone replacement therapy, but the provider instead questioned her about her identity, gave her a pamphlet on HIV, and told her to find a specialist (Kelley, 2021).

Another example of a transgender patient who was not able to access appropriate quality healthcare occured when Jay Kallio, a transgender man in his 50s living in New York, was discovered to have an aggressive form of breast cancer (Buxton, 2015). After receiving a mammogram and a biopsy, Kallio did not hear from his physician for many weeks. When he finally heard about his diagnosis, it was from the medical professional who performed the biopsy, who was shocked to hear that Kallio’s physician, a surgeon at a major New York hospital, had not informed him of the swiftly-worsening cancer. Kallio struggled to get in contact with this physician, and when he did, the surgeon began the conversation by stating that he wanted to send Kallio to a psychiatrist for his identity. Eventually, Kallio was thankfully able to transfer his case to another surgeon, and even beat the cancer in 2008, though he later succumbed to lung cancer in 2016. (Jay Kallio, n.d.) Ultimately, Kallio’s case is one that serves as a reminder of the very real potential consequences for medical transphobia.

There are, however, some of the most wretched instances of transphobia that involve harassment and blatant cruelty, such as what happened to Tyra Hunter. Another such case is that of Robert Eads, a transgender man who was taken to the emergency room in Georgia in 1996 after passing out. When he was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, he was refused treatment by more than a dozen medical practitioners. By the time he was accepted by the hospital of the Medical College of Georgia in 1997, the cancer had metastasized, and no treatment would have been able to save his life (Ravishankar, 2013). He died in 1999, and his story is told in the 2001 documentary, Southern Comfort, named after a popular transgender gathering that he spoke at after his prognosis (“Robert Eads”, 2007). His case is more similar to that of Jay Kallio than Tyra Hunter’s, but Eads’ slow and painful death was the result of medical transphobia in action.

Even the late transgender activist and author of the well-revered Stone Butch Blues, Leslie Feinberg (who used the neopronouns ze/hir), has discussed the transphobia ze faced after seeking treatment. In zir 2001 work, “Trans Health Crisis: For Us It’s Life or Death”, ze detailed how hospital staff gathered around zir, calling Feinberg “it” and “martian”. Feinberg chose to leave the hospital in question without being treated, and thankfully the illness ze had was not life-threatening, as it had been for Tyra Hunter and Robert Eads (Feinberg, 2001).

Knowing what we do about medical transphobia, how can healthcare professionals enact change within the healthcare system, ensure that transgender patients are treated equitably and ethically, and rebuild trust with the transgender community?

Leslie Feinberg urges in zir aforementioned work that decisions related to transgender patients involve transgender and gender variant people of all kinds. Ze made recommendations large and small, some of which have been implemented already. One of the simplest, which has been picked up by quite a few healthcare professionals, is to “refer to patients by their first and last names, not Mr. or Ms., sir or ma'am.” Another is a call for institutional standards (Feinberg, 2001), such as the Standards of Care developed by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH). This comprehensive document acts as a guideline for health care professionals “to provide clinical guidance for health professionals to assist transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people with safe and effective pathways to achieving lasting personal comfort with their gendered selves, in order to maximize their overall health, psychological well-being, and self-fulfillment.” (Standards of Care, 2012, p. 1)

Medical education has also been shown to have significant gaps in coverage of transgender healthcare. Fung et al. performed a qualitative review of Toronto medical residents’ knowledge and confidence in transgender care in 2016. The results indicated that residents had limited exposure to formal training in transgender medicine, as well as few mentors within their specializations who had enough knowledge to confidently educate or advise on such topics (Fung et al., 2020). If you’d like to learn more about the gaps in transgender health education, Korpaisarn et al.’s Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers reviews a number of studies on the subject and follows with a section on effective interventions, including the use of WPATH’s Global Education Initiative (GEI), which offers training and certification courses on transgender healthcare (Kopaisarn et al., 2018).

Healthcare professionals should stay up to date on legislative matters. Our previous article for Transgender Day of Visibility discussed this at length and included a number of resources for education and for action. If you would like to learn more about the legal side of transgender health, that piece would be a good starting point. Likewise, if you would like to learn more about some terminology related to transgender individuals in a healthcare setting or about how to build rapport with transgender patients or otherwise equitably treat transgender patients, Klein et al.’s Caring for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Persons: What Clinicians Should Know, is another useful resource.

Unfortunately, transphobia may persist in society and healthcare. It is unfortunately not enough to educate ourselves alone on matters of inequity and bias; the best way to support transgender patients is to speak out against transphobia when you see it. There will be times when speaking out is difficult, but when those moments happen, please remember that if even a single person had taken action, Tyra Hunter may have survived.

References

Bowles, S. (1995, December 10) A Death Robbed of Dignity Mobilizes a Community, Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1995/12/10/a-death-robbed-of-dignity-mobilizes-a-community/2ca40566-9d67-47a2-80f2-e5756b2753a6/

Buxton, R. (2015, June 15) This Trans Man's Breast Cancer Nightmare Exemplifies The Problem With Transgender Health Care, HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/transgender-health-care_n_7587506

Feinberg, L. (2001) Trans health crisis: For us it's life or death, American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), p. 897-900. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.6.897

Fox, S. D. (1998, December 12) Damages Awarded after Transsexual Woman's Death. Polare. Internet Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/20140324052938/http://www.gendercentre.org.au/resources/polare-archive/archived-articles/damages-awarded-after-transsexual-womans-death.htm

Fung, R., Gallibois, C., Coutin, A., & Wright, S. (2020) Learning by chance: Investigating gaps in transgender care education amongst family medicine, endocrinology, psychiatry and urology residents, Canadian Medical Education Journal, 11(4), p. e19-e28. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.53009

Jaffee, K. D., Shires, D. A., & Stroumsa, D. (2016) Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men, Medical Care, 54(11), p. 1010-1016. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000583

Jay Kallio. (n.d.) Compassion and Choices. https://compassionandchoices.org/stories/jay-kallio/

Kelley, J. (2021) Stigma and Human Rights: Transgender Discrimination and Its Influence on Patient Health, Professional Case Management. 26(6), p. 298-303. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCM.0000000000000506

Klein, D. A., Paradise, S. L., & Goodwin, E. T. (2018) Caring for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Persons: What Clinicians Should Know, American Family Physician, 98(11), p. 645-653.

Korpaisarn, S., Safer, J. D., & Tangpricha, V. (2020) Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: A major barrier to care for transgender persons, Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders, 19(3), p. e271-275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-018-9452-5

Main Page. (n.d.) Global Education Institute. WPATH. https://www.wpath.org/gei

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2007, January 16) Robert Eads, National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/blog/robert-eads

Ravishankar, M. (2013, January 18) The Story About Robert Eads, The Journal of Global Health. https://archive.ph/20130914005716/http://www.ghjournal.org/jgh-online/the-story-about-robert-eads/

Rodriguez, A., Agardh, A., & Asamoah, B. O. (2017) Self-Reported Discrimination in Health-Care Settings Based on Recognizability as Transgender: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Transgender U.S. Citizens, Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), p. 973-985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1028-z

Seelman, K. L., Colón-Diaz, M. J. P., LeCroix, R. H., Xavier-Brier, M, & Kattari, L. (2017) Transgender Noninclusive Healthcare and Delaying Care Because of Fear: Connections to General Health and Mental Health Among Transgender Adults, Transgender Health, 2(1), p. 17-28. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0024

Transgender Day of Rememberance. (2019, February 17) Remembering Our Dead: Tyra Hunter, https://tdor.translivesmatter.info/reports/1995/08/08/tyra-hunter_washington-dc-usa_04a01786

World Professional Association for Transgender Health. (2012) Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. 7th ed. https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/SOC%20v7/SOC%20V7_English.pdf