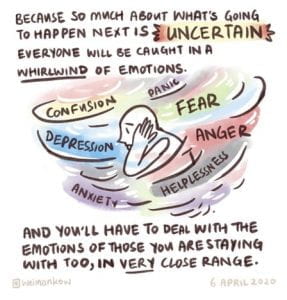

As Dr. James Griffiths noted in his recent Grand Rounds presentation, trauma shifts how the brain processes information, and we lose our capacities to reflect and to relate and to maintain our sense of identity. When faced with the fear and uncertainty of a medical illness - or a global pandemic - we lose our ability to concentrate. We cannot sit still to read the books we once loved. We pick up our pens and put them down again. Each time we try to explain what we are going through, it seems like we aren’t being clear enough, like there is no language adequate to encapsulate our experiences. Patients, family members, health care providers, we are, each of us and in our own ways, experiencing these strange times. Providers on the front lines - to whom we extend our sincere gratitude - may not be able to separate themselves from their work. Others of us, working from home for over a month now, may have established a schedule, but we still cannot bring ourselves to concentrate on the novel on our bedside table.

The New England Graphic Medicine conference was among the many that moved online this spring. The organizers added a COVID-19 comics panel discussion to the agenda. In this discussion, presenter Alice Jaggers described how the comics appearing - online, on social media channels, and via other platforms - provide a sampling of how graphic medicine is used [see: https://www.graphicmedicine.

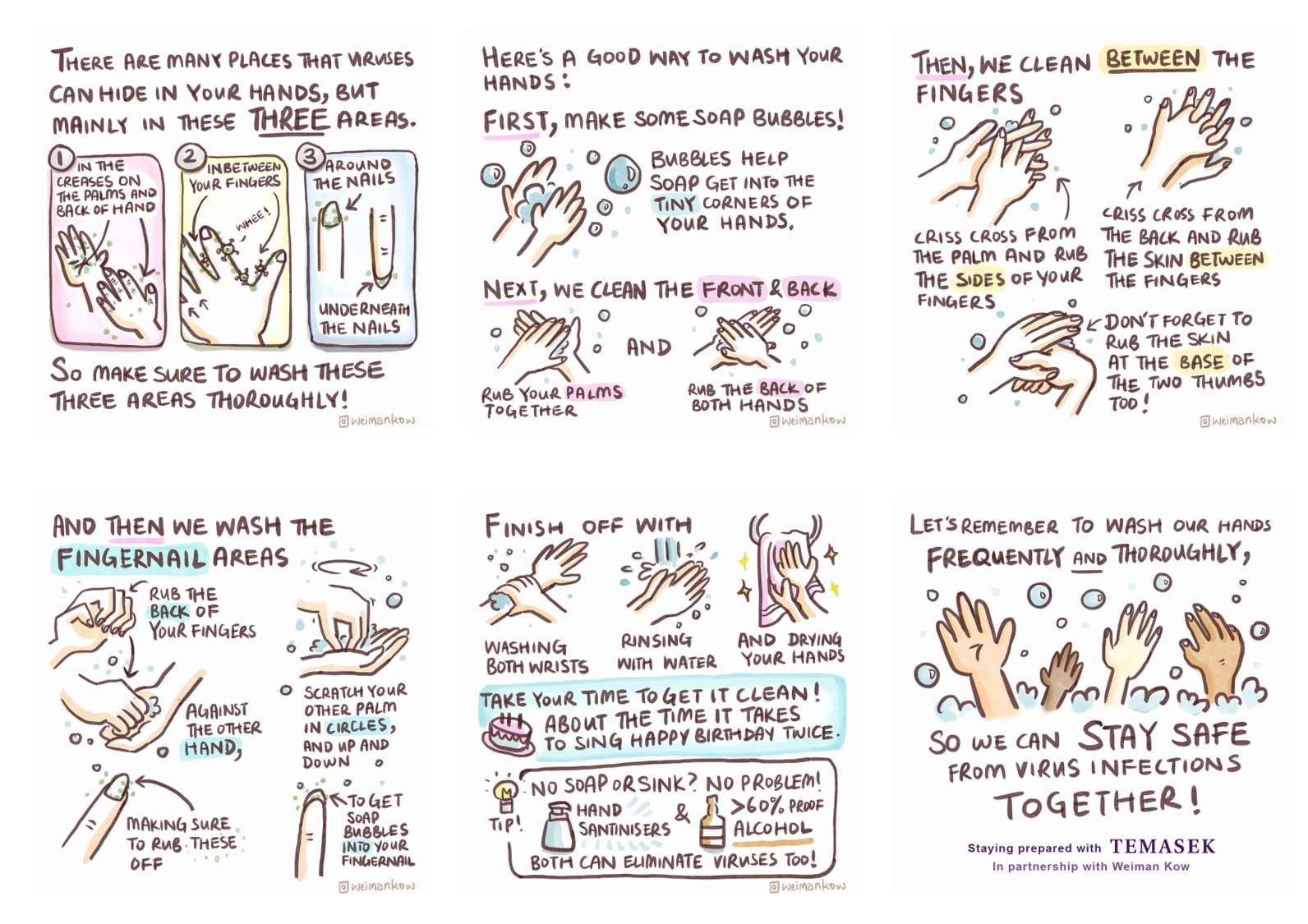

Even when we cannot focus, especially when we cannot or do not want to focus, this rich medium, with all its layers, accomplishes through the synergy of drawing, words, and dialogue, that feat of connecting us. The space between the comic panes allows us to pause and process as we encounter traumatic events and difficult emotions on the page or screen (Williams, 2012).

Graphic medicine has been accepted and embraced by long-standing institutions and publishers. The Annals Graphic Medicine Channel includes comic strips that bring to the surface struggles healthcare professionals face. In comic format, these stories are human, relatable, and non-threatening. Since 2016, JAMA has issued an annual “Best Of” list for graphic medicine. (remember to access JAMA via the Himmelfarb Library’s website; check out their medical humanities section for articles about graphic medicine and more).

A search for “Graphic medicine” in PubMed returns 155 results, with most appearing within the last 5 years. Recognizing the growth in this area, two MeSH terms were added: in 2016, Graphic Novel as a publication type was introduced and, in 2018, “Graphic Novels as Topic” with the entry term “Graphic Medicine as Topic” was added. This is defined as “Works about book-length narratives told using a combination of words and sequential art, often presented in comic book style.” Graphic medicine is a diverse and growing field, with, as described, a broadly inclusive definition. Graphic medicine is at the intersection of the already blurry spheres of health and medicine and comic style. Graphic medicine can come in the form of an Instagram post or a strip on the Annals Graphic Medicine channel or a 200-page graphic novel. The topics range from anxiety to spanish flu (both pertinent to these times). The perspective may be that of the patient or provider or the family members and friends of those affected.

The National Library of Medicine collects graphic medicine materials for several reasons, including to “record progress in [medical] research, especially from the perspective of the patient patient”, contribute to medical education, describe “policies that affect the delivery of health services” in a straightforward manner, and depict “the public’s perception of medical practice” (Tuohy & Eannarino, 2018) As they go on to state, the perspectives and stories found in graphic medicine are unique from those found in technical and research literature.

According to Dr. Griffiths, to be resilient, we must step into adversity. We can use graphic medicine to reflect, cope, and connect and to ultimately help us step into adversity.

References:

Myers, K. R., & Goldenberg, M. D. F. (2018). Graphic Pathographies and the Ethical Practice of Person-Centered Medicine. AMA Journal of Ethics, 20(2), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1001/

Tuohy, P., & Eannarino, J. (2018). Reading graphic medicine at the National Library of Medicine. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 106(3), 387–390. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.

Williams, I. C. M. (2012). Graphic medicine: comics as medical narrative. Medical Humanities, 38(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1136/