By Colleen Calhoun, Mary Anne Porto and Libby Schiller

Exotic animals have long been seen as symbols of power and democracy. Dating back to the times of Ancient Rome and Emperor Octavius, large animals such as lions, rhinoceroses, etc. have been used as leverage in bureaucracy.

Animal diplomacy is not exclusive to the Chinese. In the era of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, Egypt gave Giraffes to foreign nations. Queen Elizabeth II gave two black beavers to Canada in 1970. The Chinese originally gave Pandas away as gifts, but in 1984 the government decided to begin a 10-year loan system with annual payments.

Today, there are more than 25 zoos worldwide that have Pandas.

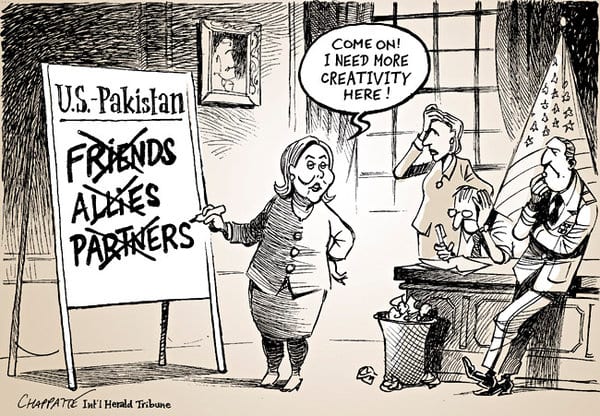

With the new loan system, China has reached out to countries in an attempt to foster relationships. More so now, China has been using Panda diplomacy to pursue economic and political ambitions as well. The Edinburgh Zoo received its pandas in 2011, setting up a deal to pay an annual fee to the Chinese government to help giant panda conservation projects in the wild. Not only is China reaching out to countries using Pandas, they are benefiting from the relationships as well. Similarly, Japan also received two pandas in 2011, and the two countries hoped it would improve relations caused by dispute over islands and their sovereignty.

China has been successful in their efforts because Pandas are very cute and many

countries would like to have them in their zoos. Pandas are a soft power tool that the Chinese have been using to increase their scope around the world. More so than diplomatic relationships, China has seen more growth in economic relationships with Panda diplomacy.

According to a BBC article, Scottish exports to China have almost doubled in the past five years. Similarly, Panda loans in Canada, France and Australia coincided with trade deals for uranium. The article also said, “If a panda is given to the country, it does not signify the closing of a deal – they have entrusted an endangered, precious animal to the country; it signifies in some ways a new start to the relationship.” This shows that China is not looking to give countries Pandas and complete a one time deal. They are looking to foster long-term relationships, especially regarding economics.

As a soft power tool, the Chinese government can use cute, cuddly Panda to increase economic growth, not only for the time-being, but over an extended period of time.

There are many challenges facing those who wish to replicate animal diplomacy efforts of the past. Animal advocates have challenged the practice as they say it commercializes animal lives and puts stressors on already vulnerable endangered species. Others want more transparency about where fees for loans go. Countries who choose to do so should consider making their funding more transparent and perhaps shifting away from a funding model all together, instead focusing on just awareness, to reduce criticism.

Countries should also consider the logistics of their animals, making sure the animals are able to travel and not endangered. They should also ensure that the animals are representative of their countries and reflect positively on them.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author(s). They do not necessarily express the views of either The Institute of Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or The George Washington University.