By Kayla Malcy, MA International Affairs, 2022

The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir has existed since partition in 1947. Kashmir has precipitated 2 of the 3 Indo-Pakistani wars and a slew of militant groups and attacks on both sides of the line of control. Alongside the physical violence of the Kashmir conflict, there has been a clear formation of national narratives to suit each country’s objectives. If India and Pakistan plan to move towards sustained peace, they will have to reconcile their opposing identity narratives and repair their relationships with the Kashmiri people.

The conflict explained

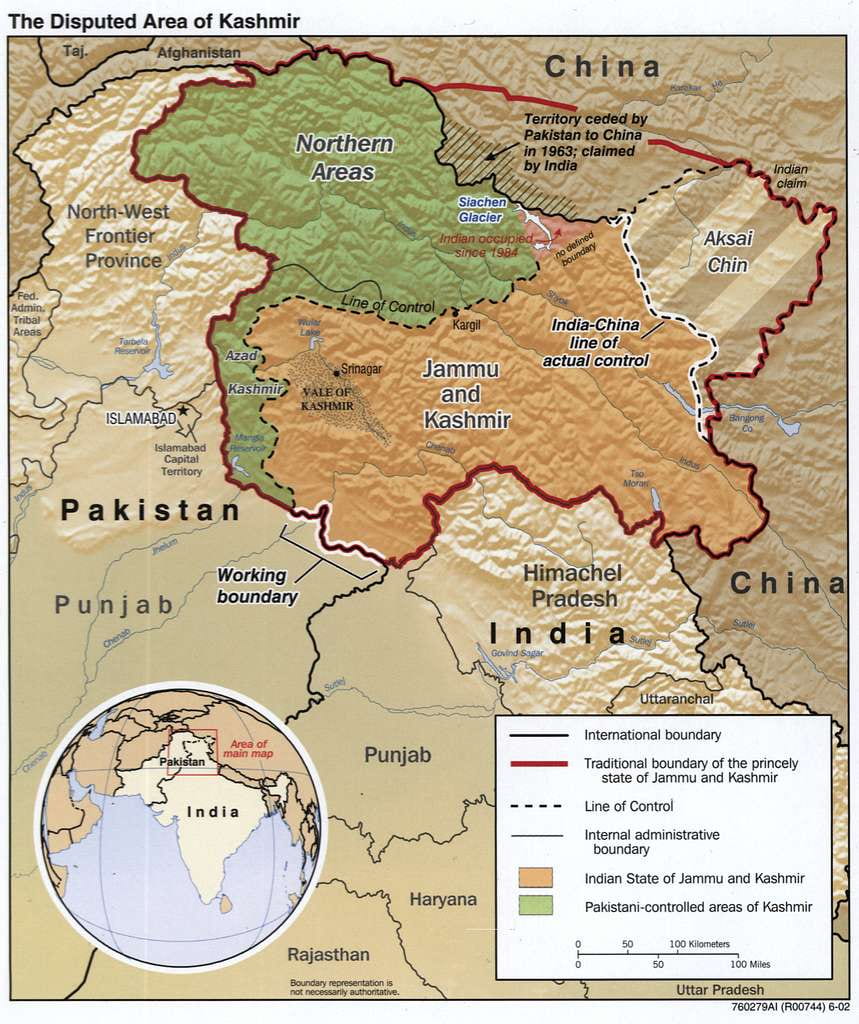

The partition of British India placed Kashmir in a nearly impossible position. While the Maharaja of Kashmir, part of the Hindu minority ruling a Muslim majority, wished for independence, both India and Pakistan wanted Kashmir within their own borders. The Maharaja agreed to join the Indian state in exchange for protection from Pakistani forces, instigating the first Indo-Pakistani war as well as the cascade of conflicts that followed. The current line of control divides the Kashmiri territory into Indian administered Kashmir and Pakistan administered Kashmir.

Rising tensions

With talks coming to a standstill in 2016, Kashmir has seen a marked increase in violent conflict. Attacks by militant groups against the Indian military were seen in both 2017 and 2018. Indian security forces clashed with both militants and demonstrators. An attack on an Indian Army convoy by the terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammad, associated with the Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), killed 40 soldiers in February of 2019 reigniting the prolonged conflict between India and Pakistan.

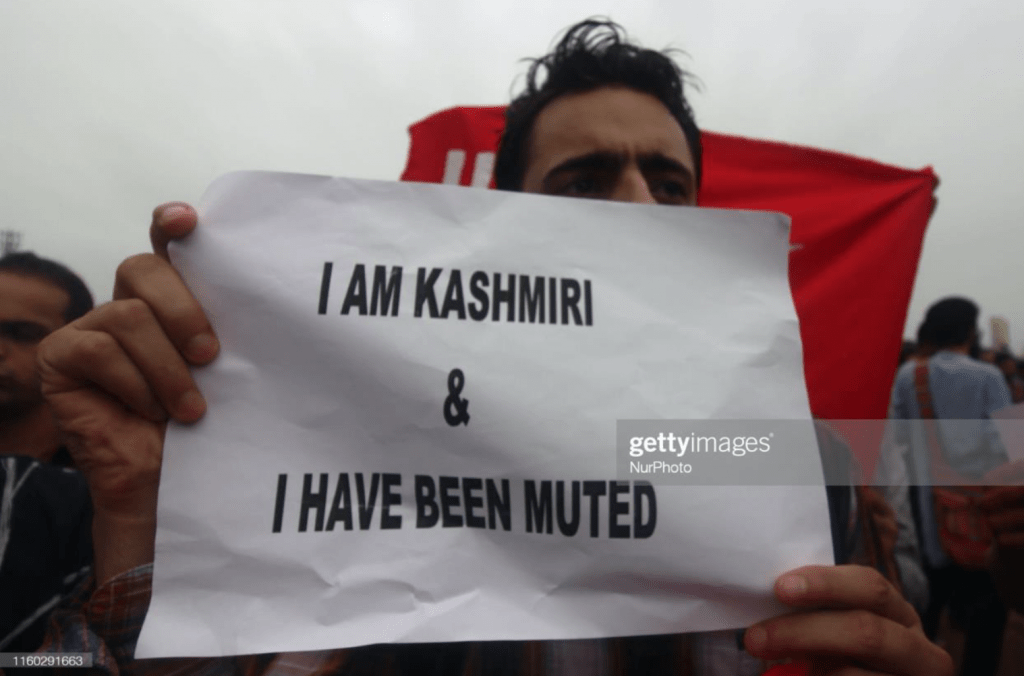

In August 2019, India moved thousands of troops into Kashmir. The Indian government then revoked Article 370, which gave Jammu and Kashmir its partial autonomy and statehood, and 35A, which provided residents privileges such as land ownership. Cellular and landline services were shut down to all of Kashmir and India imposed the longest ever internet shut down in a democracy.

Pakistani National Identity Narratives

Pakistan’s founding identity as a safe haven for Muslims reinforces the sentiment that Kashmir, with a population roughly 60% Muslim, belongs with it. Arguments over the meaning of Pakistan’s name also contribute to its identity. In Pakistan’s official language of Urdu, ‘Pak’ means pure. ‘Pak’ then combined with ‘-stan’ forms the meaning of ‘the land abounding in the pure’ or as it is often translated, ‘the land of the pure’. An alternate reading of Pakistan’s name is as an acronym for the four northern states of former British India: Punjab, Afghania, Kashmir, and Sindh. In both cases, the retention of Kashmiri territory is critical to the Pakistani national identity.

A large facet of both the Pakistani and Indian identity narratives is opposition to the enemy. For Pakistan, riling up anti-Indian sentiment can distract from other political issues. In their view, India is a tyrant abusing the Muslim Kashmiris, which Pakistan, as a Muslim country, has the duty to protect. Additionally, the idea that India has never fully accepted partition and is simply waiting to take Pakistan back is thrown out to heighten Pakistani feelings of defensiveness.

Indian National Identity Narratives

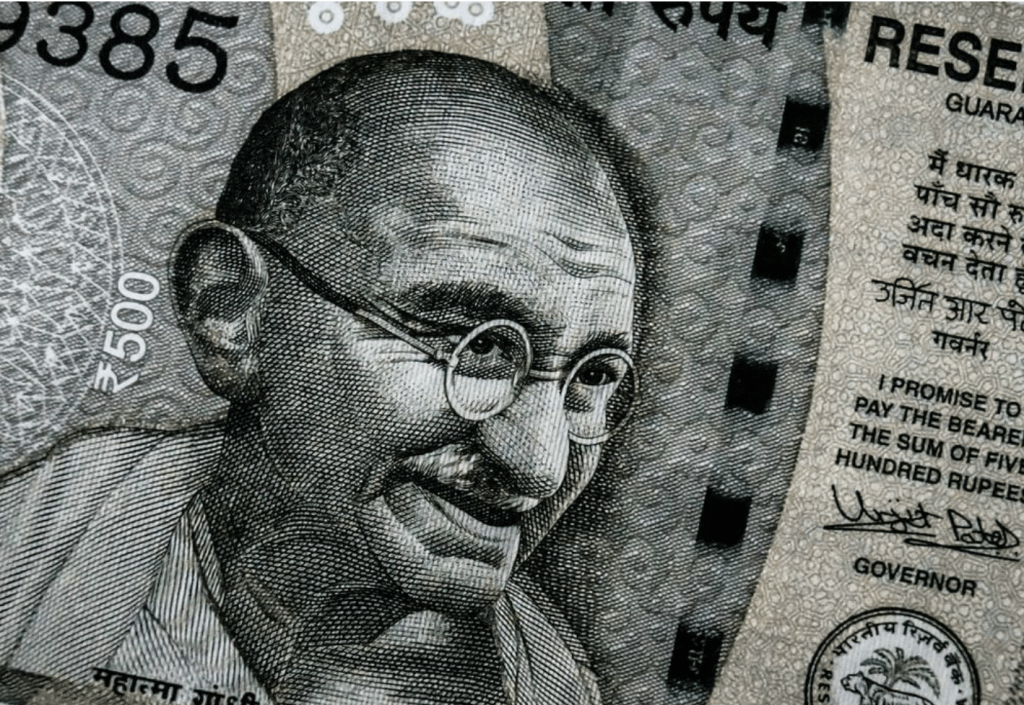

India’s population is majority Hindu and while the Indian constitution guarantees freedom of religion, the governing party, the BJP, is Hindu nationalist at its core. These ideals and the construction of Muslims as ‘the other’ puts Indian national identity in direct opposition to Pakistani national identity. India takes enormous pride in being world’s largest democracy. This narrative of democratic idealism has often shielded India from criticism among western powers. Another aspect of Indian identity is self-reliance which can be traced back to Gandhi. Even today PM Modi’s platform contains five pillars of self-reliance.

Just as Pakistani politicians use anti-Indian sentiment, Indian politicians use the same tactic of riling up anti-Pakistan sentiment in order to distract from other political issues. In fact, 2019 Pew Research surveys show that 76% of Indian’s see Pakistan as a threat; only 7% do not view Pakistan as a threat. Claims of Pakistani sponsored violence in Kashmir never fail to anger the populace of India and redirect attention from other issues. India sees itself as the rightful heir to Kashmir due to the Hindu Maharaja’s decision to join India. India focuses in on this claim in their attempts to delegitimize Pakistani claims to Kashmir.

Battle of the Narratives

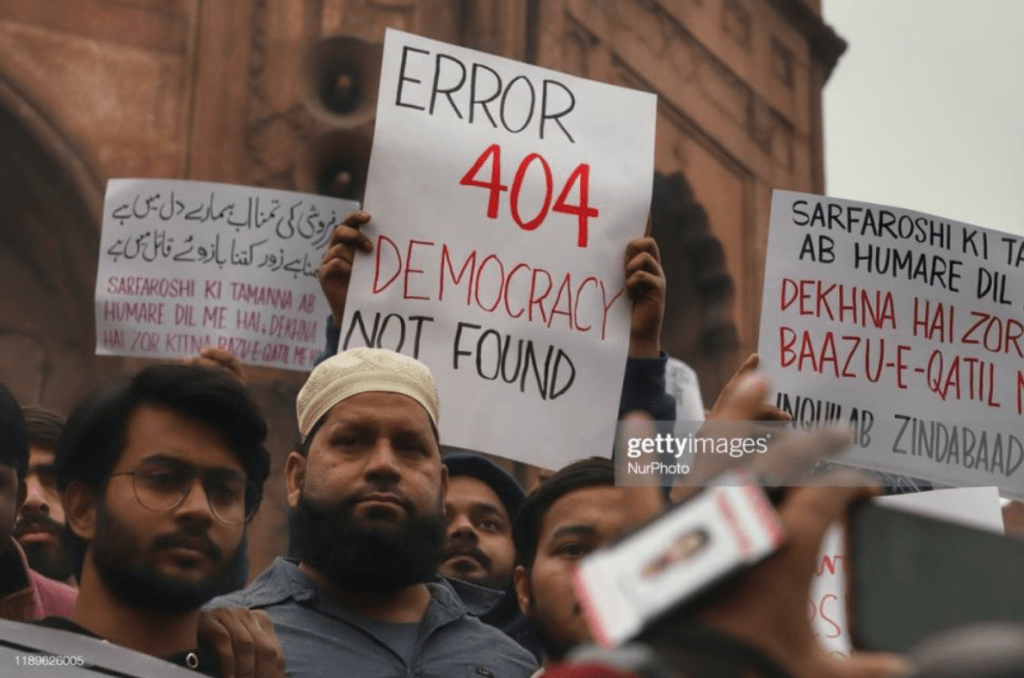

These conflicting identity narratives play out in Kashmir, especially the religious ones. Pakistani claims that India’s recent actions are proof of India targeting Muslim populations in Kashmir and stripping them of their rights. India claims that Pakistan is a hotbed for Islamic terrorism and is directly responsible for militant attacks against Indian security forces in Kashmir. Calling out the other’s actions in this way only serves to increase blame and widen the gap in dialogue.

The weight of both narratives changed with the 2019 events and the release of the 2019 UNHCR report on Kashmir, which concerned abuses by security forces on both sides of the line of control. With the repeal of Article 370 and subsequent shutdown of internet services and Kashmir lock down, India has lost some of the legitimacy its democratic narrative carried before. Revoking Article 35A has also caused concerns that the BJP is attempting to change the religious demographics of Kashmir by opening up property ownership to the non-Kashmiri Hindu majority in India. These actions coupled with recent announcement of India’s democratic backsliding further solidified the Pakistani narrative of an unjust India with no respect for Muslims as an occupational force, not a rightful ruler.

While opinions within Kashmir remain divided as to whom Kashmir belongs, if anyone at all, movements to reinstate Article 370 and, alternatively, to separate from India continue in Kashmir. The Indian and Pakistani focus on messaging to the opposing government has long sidelined the Kashmiri people leaving their voices unheard. If any progress is to be made both India and Pakistan will need to address, at a minimum, the aspects of their identity narratives based on the fear of the other.

For a detailed analysis by the author on the subject, Click Here.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

Main photo: Authorities clash with demonstrators, provided by Kashmir Global