By Adeniyi Funsho, MA Media and Strategic Communications ’22

The latest bombing attack of the Abuja-Kaduna bound train by Boko Haram speaks to the continuous reign of terrorism, and extremist narratives against Nigeria. The latest attack is coming off the back of countless others that spread from the northeast to as far as the south of Nigeria. Nigeria, a former British colony has gone through several turbulent moments in its history as a nation leading to it becoming a democratic state, running a democratic system. As a nation, its master narrative is rooted in its diverse culture, tribes, religions, and hard-fought democracy. One threat to Nigeria’s master narrative is Boko Haram, an Islamic group founded by Mohammed Yusuf, which grew out of a cell of Muslim clergies and followers in Maiduguri, a state in the northeastern region of Nigeria. Since 2009, Boko Haram has been disrupting both the economic, and social life of Nigerians with a total of over 34,000 deaths, the latest killing of passengers traveling in a train bound for Kaduna adds to the increasing number of deaths by the terrorist group.

Courtesy of Vanguard News: Abuja-Kaduna bound train attacked by Boko Haram killing over 15 passengers and over 200 wounded.

Boko Haram translates to ‘no to western education,’ and western ideologies describe the archetype of its master narrative as a group that is completely opposed to westernization. Unlike other ethnic militias, Boko Haram does not appropriate its ethnic Kanuri nationalist rhetoric to demand national representation for the northeast region within the Nigerian democratic system; instead, Boko Haram’s goal is the pursuit of an Islamic caliphate, a political structure, and a system of government based on Tawid ‘God’ law. Boko Haram is in opposition to what it calls ‘man-made’ laws of western democracy and the westernized culture under which the Nigerian system operates. Most importantly, however, we need to understand that Boko Haram’s narratives are founded on the “Salafi-jihadi” movement of Islam, a modern-day movement traceable to the middle east which developed roots connecting it to northern Nigeria. Their beliefs are predicated on a “Quran-only” doctrine, that strongly rejects westernized culture, and systems, owing to that reason the earliest people that first came into contact with the group branded them ‘Boko Haram’ a narrative that describes their utopia of ‘no to education’.

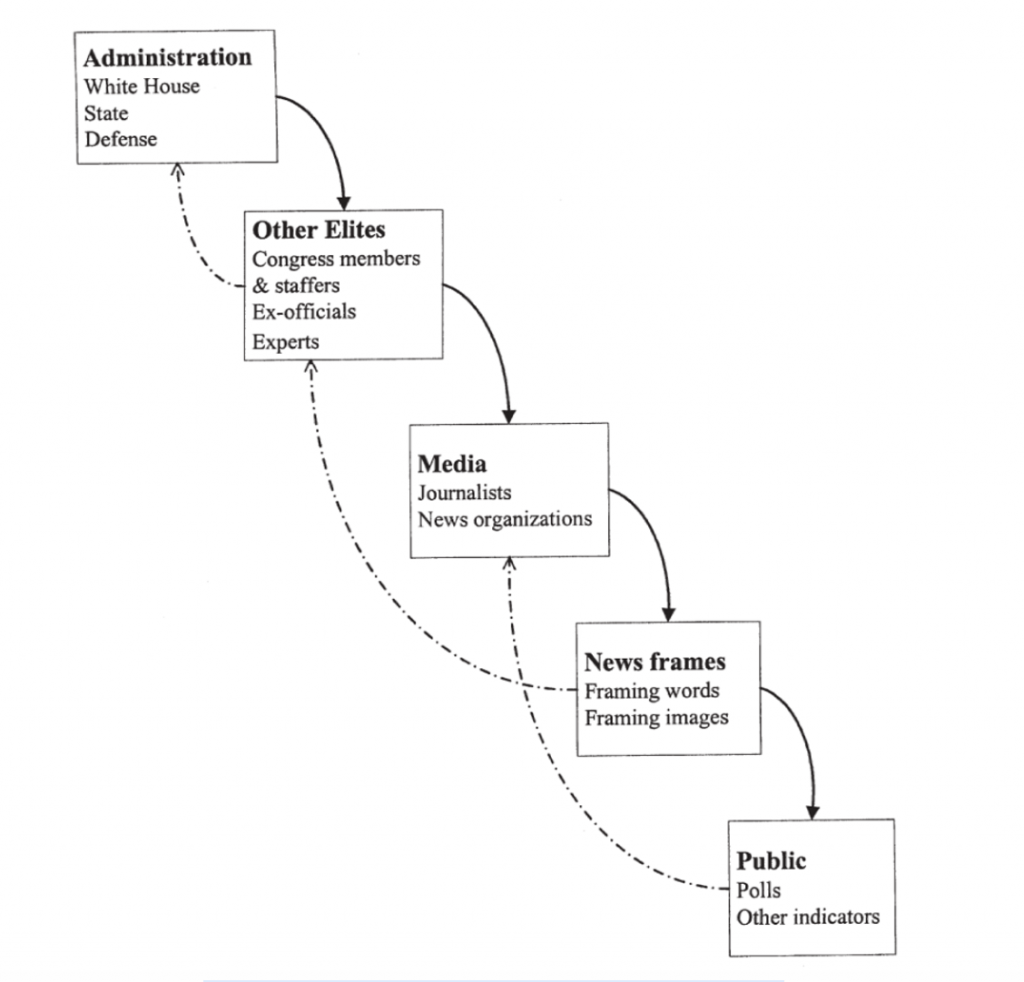

Specifically, Boko Haram’s Salafi-jihadi “Quran-only” identity reveals the ‘Islamist extremism’ ideology of the group, how they think, how they organize, the goals they pursue, and the reason why their narrative and activities are engrained in tough-talk and violent videos laundered through the media ecology. We get an understanding of their strategic narrative and the reason why they see an Islamic state as jihadism, and the only solution to resolve their issues with Nigeria. Boko Haram’s narratives for an Islamic state which previously appeared to have been ignored by the Nigerian state and international audiences got international attention when in April 2014, it ransacked the small town of Chibok, Maiduguri, and kidnapped 276 Chibok schoolgirls returning from school. In its messaging to Nigeria and the rest of the world, Boko Haram released a video via YouTube showing the girls as a ransom for the release of its members, and demands for an Islamic state. Nigeria’s counternarrative of peace and the use of Islamic commands on education as an appeal to Boko Haram to release the girls failed. However, it succeeded in destroying the conditions that make Boko Haram’s narratives plausible, communicable, and intelligible. It galvanized international and local nonstate actors, and media to frame the counternarrative of #BringBackOurGirls emphasizing the urgency for their unconditional release and their immutable right to education.

Courtesy of Channels News: Images of Chibok Schoolgirls that escaped from Boko Haram’s Kidnapping Camp

In order for Nigeria to counter Boko Haram’s extremist narratives, it should frame Boko Haram in a way that counters the group as following a false narrative of the ideology of true Islam. Framing should be crafted on peace and not violence, and Nigeria should heighten its frames on Islam as a religion that entertains peace ‘salam’ as its identity and one that abhors violence. Most importantly, Nigeria’s frames should heighten the sayings of the Islamic prophet on education and the ones whereby he implored its followers to live in peace and tolerance with their neighbors.

This should be supported by strategic use of the media ecology to counter the Boko Haram identity narrative of ‘no to education’. Nigeria’s counternarrative to Boko Haram should be based on the true Islamic authority of the prophet of Islam as he expressed his love for knowledge and enjoined his followers to seek education even if it were to be as far as China!

For more on the topic by the author, please click here.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

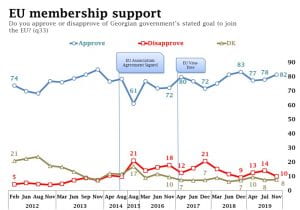

This perspective feeds into Georgian identity narratives, which are those that describe Georgia’s identity as a country. These identity narratives depict Georgia as a strong, independent, and unified state which governs itself. Identity narratives can also constrain a nation’s behavior. Georgia, for example, values self-governance and is a nascent democracy, and thus is expected to behave as such. Additionally, Georgian nationalism has become increasingly important since it seceded from the Soviet Union in the 1991 referendum. This helps to explain why Georgia views the Abkhazia and South Ossetia controversy as an occupation of their territories, rather than accepting Russia’s narrative of support for independent states.

This perspective feeds into Georgian identity narratives, which are those that describe Georgia’s identity as a country. These identity narratives depict Georgia as a strong, independent, and unified state which governs itself. Identity narratives can also constrain a nation’s behavior. Georgia, for example, values self-governance and is a nascent democracy, and thus is expected to behave as such. Additionally, Georgian nationalism has become increasingly important since it seceded from the Soviet Union in the 1991 referendum. This helps to explain why Georgia views the Abkhazia and South Ossetia controversy as an occupation of their territories, rather than accepting Russia’s narrative of support for independent states.