By Jowen H. Ortiz Cintrón, MA Media and Strategic Communication, 2022

Three Things that statehooders should fix in their narrative

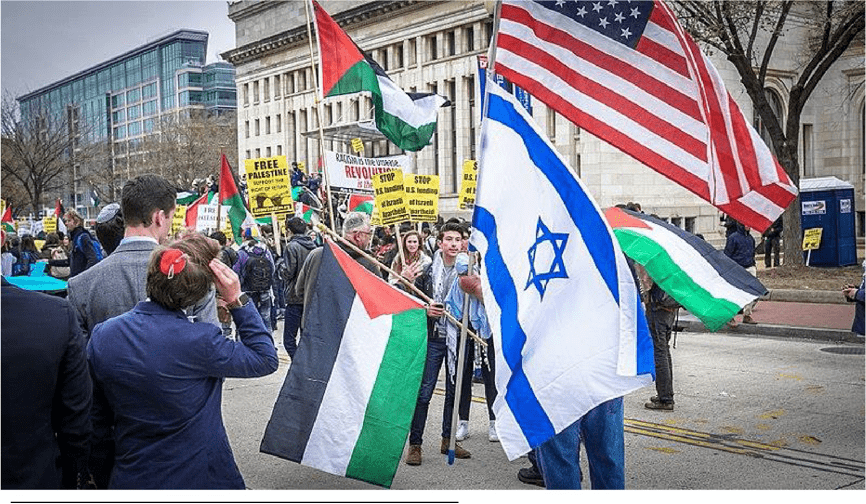

Puerto Rico is not legally a country but is the longest-standing colony in the world that has its own culture and national identity. Since 1898, it’s been a territory of the United States, as little has been done to change that at a federal level.

After plebiscites where Puerto Ricans asked for statehood, the New Progressive Party has built a narrative where Puerto Ricans have called on the United States, the banner of democracy, to allow Puerto Rico to join the United States as a state. They have appealed to the Republican’s patriotic sense, recalling the service of Puerto Ricans in the military and contributions to the victories and defense of the U.S.. For Democrats, they mention the commitment that the United States maintains with human rights, reminding them that respecting the democratic rights of Puerto Ricans is part of the human rights that the United States must defend.

While those factors are true, their narrative has big flaws that makes it difficult to garner support behind the cause from both sides of the aisle. Here are three aspects of the pro-statehood narrative that must repaired for a successful pro-statehood campaign.

- The claim: Puerto Ricans have democratically chosen statehood

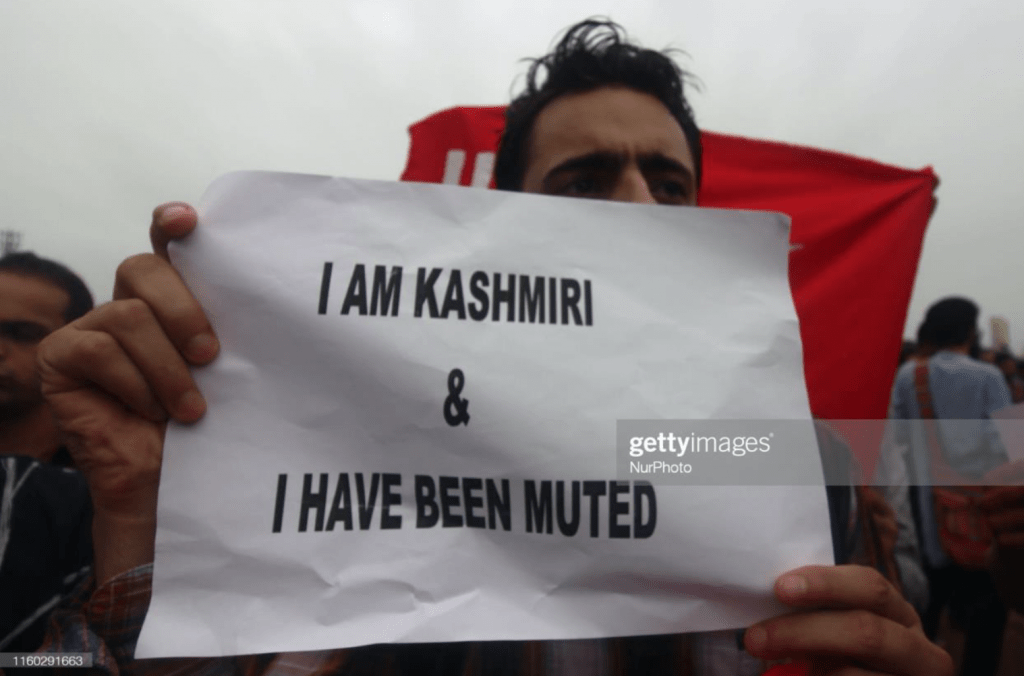

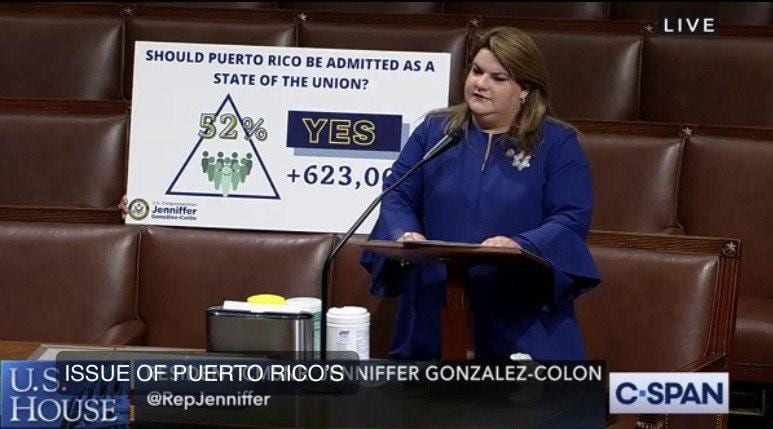

One important aspect of the pro-statehood narrative is that Puerto Ricans have asked for statehood in different plebiscites (2012, 2017, 2020). In those three democratic exercises, statehood has won the popular vote. In 2012, statehood won with 61%; in 2017, with 97.18%; and in 2020, with 52%. While it does seem like statehood enjoys wide support in Puerto Rico, the plebiscites have been ridden with controversy over the way the choices were phrased, and over the lack of participation.

This has led politicians, like Ocasio-Cortez and Velázquez, to not trust the results, because they question if it is truly democratic to let less than half of the population decide the future of an Island. In this way, questions are raised as to whether statehood is actually the desire of Puerto Ricans.

By not correctly acknowledging the lack of participation in the democratic process, the promoters of Statehood have allowed a narrative to be drawn where the low participation is attributed to a decline in support for statehood. This has distanced highly valued progressive Democratic voices from supporting statehood projects, and they have preferred to present the Self-Determination Act.

- The Messengers: NPP’s history of fraud and corruption

The supporters of statehood in Puerto Rico are aligned with the New Progressive Party (NPP). The party proved to be a political force. However, in recent years, support for the party has waned.

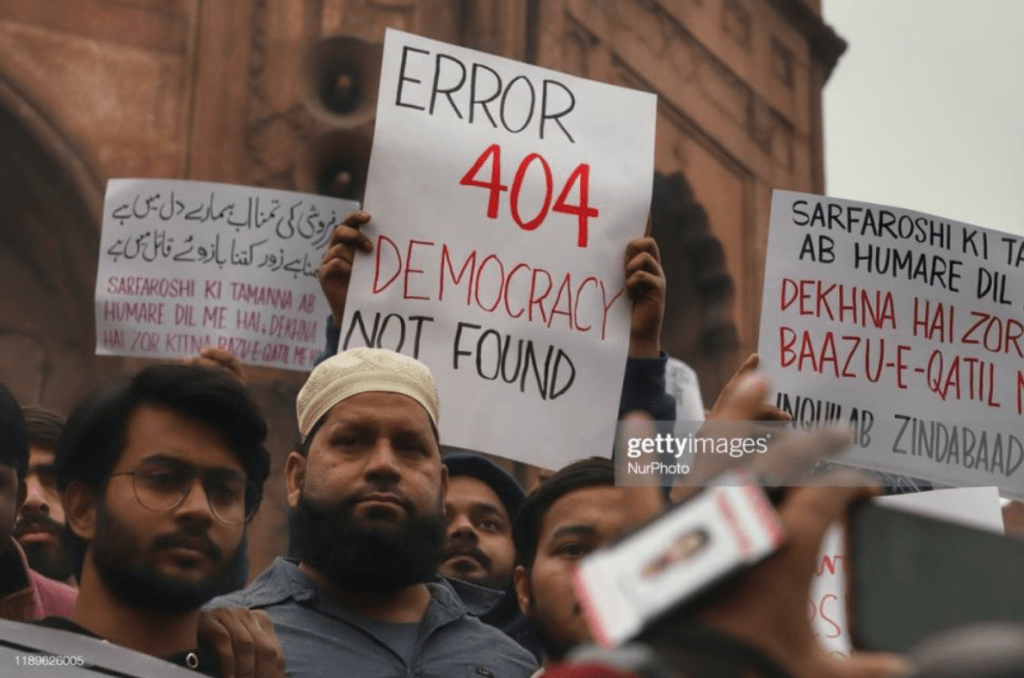

The history of corruption the party carries is a reason for the loss of support. The party has been marked by arrests of mayors, representatives, senators, heads of agencies, and other public employees accused and convicted of embezzlement, theft, and corruption of power. During the four years from 2016 to 2020, after Hurricane María and other crises in Puerto Rico, then-Governor Ricardo Rosselló was forced by the people to resign due to a large number of cases of corruption and nefarious handling of the country’s public funds and recovery aid, worsening the crisis that Puerto Ricans are experiencing, among other reasons.

Jorge de Castro Font is a former NPP senator arrested in 2008 on charges of fraud and conspiracy. The following year he pleaded guilty to 21 counts. He was sentenced in 2011. Source: Primera Hora

“Public corruption poses a threat to our democratic institutions and erodes trust in government.”

– US Attorney Stephen W. Muldrow about corruption in Puerto Rico.

The corruption and the great public debt of the archipelago have given Puerto Rican politicians a bad name at the federal level, in which it is questioned what could be the value of such a corrupt country to the democracy of the United States. This thought is shared by members of the Republican party mainly, who strongly oppose statehood for Puerto Rico3.

- Opposed Narratives: “More federal funds for Puerto Ricans”

A campaign promise by everyone running for office in the NPP is that, with Puerto Rico being a state, citizens would have access to more federal aid.

During the recent natural disaster crises in Puerto Rico, Governor Pierluisi, Resident Commissioner González and other statehood allies in Congress, have emphasized the importance of helping the American citizens on the island with statehood and more federal funds for education, Medicaid and crisis relief expenses.

While this narrative resides in the hope of appealing to the Democratic base, it further alienates Republicans. Publicly building a narrative in favor of increased federal funding has caused the “welfare queen” narrative to take a new angle against Puerto Rico and statehood. It had demonized the idea behind delivering more help to Puerto Ricans. Given the island’s history of embezzlement and poverty, Republicans have identified the island as a monetary burden and have repeatedly opposed the idea of giving more funds to the island.

The call to solve Puerto Rico’s status situation has been long and overdue. To solve it, political leaders should present a narrative strong enough to appeal to United States’ politicians. Nonetheless, the supporters of statehood haven’t been able to build a cohesive narrative that delivers a proper claim, with a credible messenger, and that coexists with the narratives of the United States. The narrative fails to appeal to Democrats and Republicans alike, creating riffs in what is supposed to be a human rights decision.

For a detailed analysis by the author on the subject, Click Here.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.