An early Christmas present arrived in the mail today – a new book called Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism (Meg McLagan and Yates McKee, eds., Zone Books, 2012.)

The “visual culture of nongovernmental activism” seems like an important topic for U.S. public diplomacy practitioners to consider. Even though public diplomacy isn’t exactly nongovernmental, neither does it  represent the prevailing governing power of the countries in which public diplomats work. And in “making the case for America” in those foreign lands, we are very much activist, vying for attention along with non-governmental (and other-governmental) efforts of every stripe. We may ally ourselves enthusiastically with some causes, for example women’s empowerment. We may argue against others, for example restrictions on free speech deemed blasphemous. But we are always one voice among many, without the authority (however defined or felt) that a government body carries in its own country.

represent the prevailing governing power of the countries in which public diplomats work. And in “making the case for America” in those foreign lands, we are very much activist, vying for attention along with non-governmental (and other-governmental) efforts of every stripe. We may ally ourselves enthusiastically with some causes, for example women’s empowerment. We may argue against others, for example restrictions on free speech deemed blasphemous. But we are always one voice among many, without the authority (however defined or felt) that a government body carries in its own country.

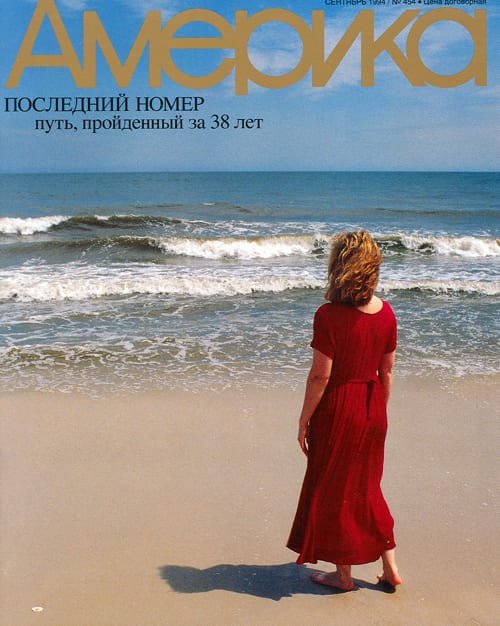

And of course, one of public diplomacy’s key resources is visual culture. From the first great expansion of  U.S. public diplomacy during the Cold War period, the U.S. looked for ways to make visual our ideas, our values, our culture. Jazz Ambassadors did not tour just so people could hear their music; these mega-stars were sent abroad so that their photos would be on the front page of every newspaper, perhaps shaking the hand of a prime minister or jamming with local musicians. Jeeps and trucks carried USIS officers to remote areas with movies and portable generator-run projectors. Every month USIS distributed glossy color-photo magazines in Russian, Arabic, Spanish, French, and other languages. U.S. cultural centers were and are full of posters, photographs – even décor – supporting our particular “cause,” i.e., America itself. With the advent of satellite television in the 1980’s, USIA under Charles Wick eagerly embraced the opportunity to engage via this new medium. Interestingly, the first and most prominent use of USIA’s “Worldnet” television was to bring together multi-country audiences in mutual discussion and debate.

U.S. public diplomacy during the Cold War period, the U.S. looked for ways to make visual our ideas, our values, our culture. Jazz Ambassadors did not tour just so people could hear their music; these mega-stars were sent abroad so that their photos would be on the front page of every newspaper, perhaps shaking the hand of a prime minister or jamming with local musicians. Jeeps and trucks carried USIS officers to remote areas with movies and portable generator-run projectors. Every month USIS distributed glossy color-photo magazines in Russian, Arabic, Spanish, French, and other languages. U.S. cultural centers were and are full of posters, photographs – even décor – supporting our particular “cause,” i.e., America itself. With the advent of satellite television in the 1980’s, USIA under Charles Wick eagerly embraced the opportunity to engage via this new medium. Interestingly, the first and most prominent use of USIA’s “Worldnet” television was to bring together multi-country audiences in mutual discussion and debate.

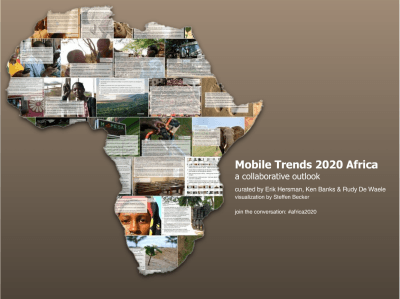

In the past couple of decades, non-governmental and civil society organizations have proliferated across the globe. In wealthier countries, philanthropy and sometimes government grants provided support. In the developing world, international donors channeled development assistance funds to and through such  groups. Even before the Internet became widely accessible, NGOs expressed their activism visually, via photography, posters, videos, theater. Some development agencies ventured deep into visual culture territory, funding local NGO partners to produce films and television programs designed to promote positive actions such as conflict resolution or combating HIV/AIDS. Non-governmental organizations around the world became sophisticated in working with visual culture. Under-funded public diplomacy organizations have felt the pressure.

groups. Even before the Internet became widely accessible, NGOs expressed their activism visually, via photography, posters, videos, theater. Some development agencies ventured deep into visual culture territory, funding local NGO partners to produce films and television programs designed to promote positive actions such as conflict resolution or combating HIV/AIDS. Non-governmental organizations around the world became sophisticated in working with visual culture. Under-funded public diplomacy organizations have felt the pressure.

Today, we all continue to be amazed at the impact and promise of digital media. Digital and social media  most certainly multiply our ability to communicate, but they expand the opportunity exponentially to those who may not have much in the way of funds, but who do have the passion, energy, and creativity to produce powerful images that draw us to their message. In this significantly more crowded visual-culture landscape, the U.S. will likely continue to focus on innovative ways to maintain our profile and to partner with other visual-culture organizations to tell America’s story. But this new book is a reminder that in the 21st century, communicating “who we are” is losing ground to communicating “what must change” — with real implications for public diplomacy.

most certainly multiply our ability to communicate, but they expand the opportunity exponentially to those who may not have much in the way of funds, but who do have the passion, energy, and creativity to produce powerful images that draw us to their message. In this significantly more crowded visual-culture landscape, the U.S. will likely continue to focus on innovative ways to maintain our profile and to partner with other visual-culture organizations to tell America’s story. But this new book is a reminder that in the 21st century, communicating “who we are” is losing ground to communicating “what must change” — with real implications for public diplomacy.

In any case, it’s exciting when a book provokes so much thought via the title alone. And now I see that already on p. 14 there’s a discussion of Walter Benjamin on the “’aestheticizing of politics’ by fascism” in the 1930’s, which somehow got me thinking about the global reach of U.S. consumer culture and how this also shapes the landscape in which we public diplomacy practitioners work. Sounds like a topic for a future blog post!

Keep this going please, great job!|