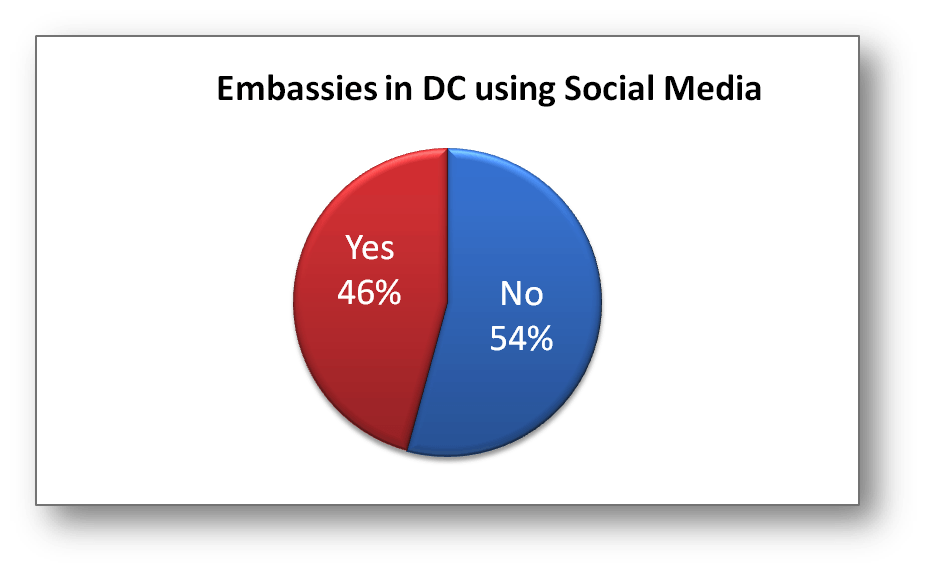

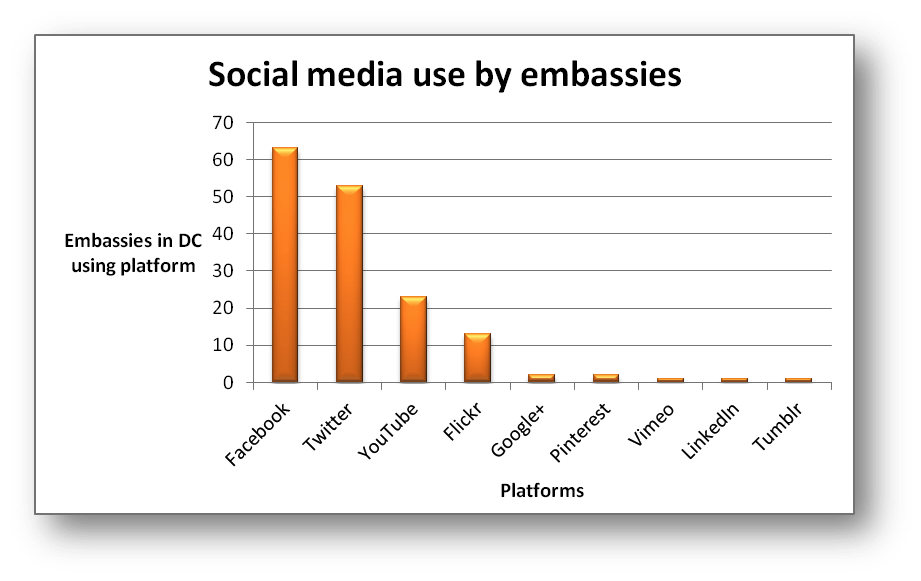

The first post in this series explained how many embassies based in Washington DC are using social media and which platforms embassies most frequently use.

After looking at embassy presence across all platforms, Facebook and Twitter proved to be the two most popular – over 50 embassies in Washington DC were identified as having Twitter accounts and 60 embassies had Facebook accounts

Of the social media platforms identified in our earlier piece, Twitter makes data most easily available and with least restrictions through their API (Automated Programming Interface). As a result, we have focused on Twitter rather than Facebook for this post, although we acknowledge the total number of DC Embassies using Facebook is slightly greater than those using Twitter.

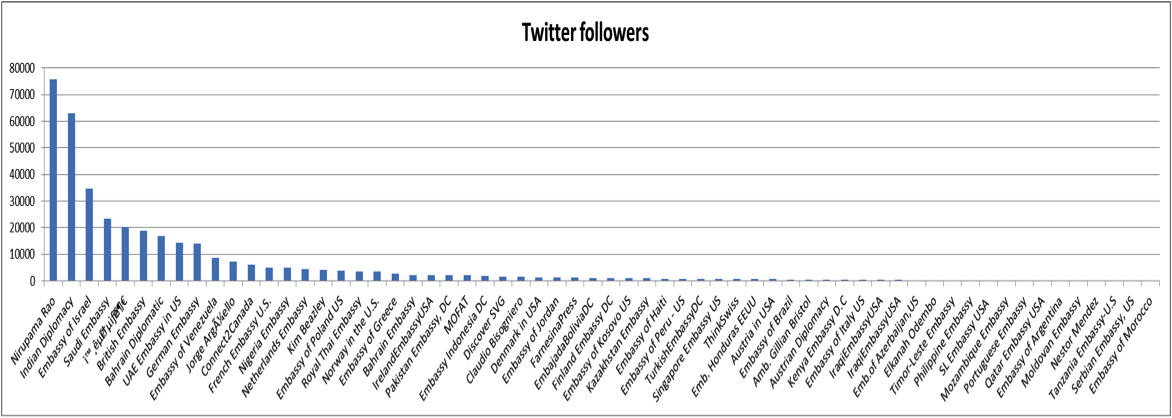

When social media and twitter specifically are discussed within the context of Public Diplomacy, one of the frequently cited metrics is the number of followers. While this is a frequently stated metric, when stated about a single Twitter account it is at very best a tactical question, rather than an indicator of a successful strategy – unless getting followers is the end goal of using a Twitter account for Public Diplomacy. One way this metric can be a little more useful is to put it in the context of others in the same field, or in this case other Embassies in DC. While this is still relatively limited in its utility, there is at least a comparative element.

The above chart shows the number of followers for all the Twitter accounts that were found during the initial research phase. As noted on the chart, the Twitter account for Nirupama Rao, India’s ambassador to the U.S.- @NMenonRao, has the most followers. At the time of the making of the chart, she had around 75,000 followers. At the time of writing this post, about six weeks later, her followers were close to 92,000. Clearly she is doing something right on Twitter that she was able to gain that many followers in such a short amount of time. A quick glance at her account shows that she tweets consistently, which is crucial to acquiring and maintaining followers, and that she was on Foreign Policy Magazine’s list of 100 Womerati which is a list created after there was a lack of women in Foreign Policy’s list of 100 Twitterati.

The 100 Womerati list is a group of women that are deemed by Foreign Policy as “100 female tweeters around the world that everyone should follow.” This could explain the extraordinarily high number of followers that she has, but is probably not the entire reason. The next highest number of followers is the Indian Diplomacy Twitter account (@IndianDiplomacy) which is the dedicated Twitter account of the Public Diplomacy sector of India’s Foreign Ministry. The fact that they have a dedicated account for public diplomacy demonstrates just how devoted they are to using social media to engage international audiences. This account is not directed solely at the United States which may account for its high number of followers in relation to the other accounts on this chart. On the other side of the chart, we see several embassy Twitter accounts that have few to no followers. This is caused mainly by two problems: no one knows the account exists (i.e. it’s not linked to the embassy’s web site) or the account is not maintained (i.e. no one is sending tweets).

Which embassies follow each other?

Moving away from a direct comparison of follower numbers, another indicator to consider is whether others in the same field think an account is worth following. This might give a comparative sense of authority around a particular issue or area of activity. In this case, while Embassies may at some level compete to represent their respective national interests, it is rarely a zero-sum proposition. As a result, there are many opportunities to collaborate and where a positive outcome for one Embassy is equally positive for another.

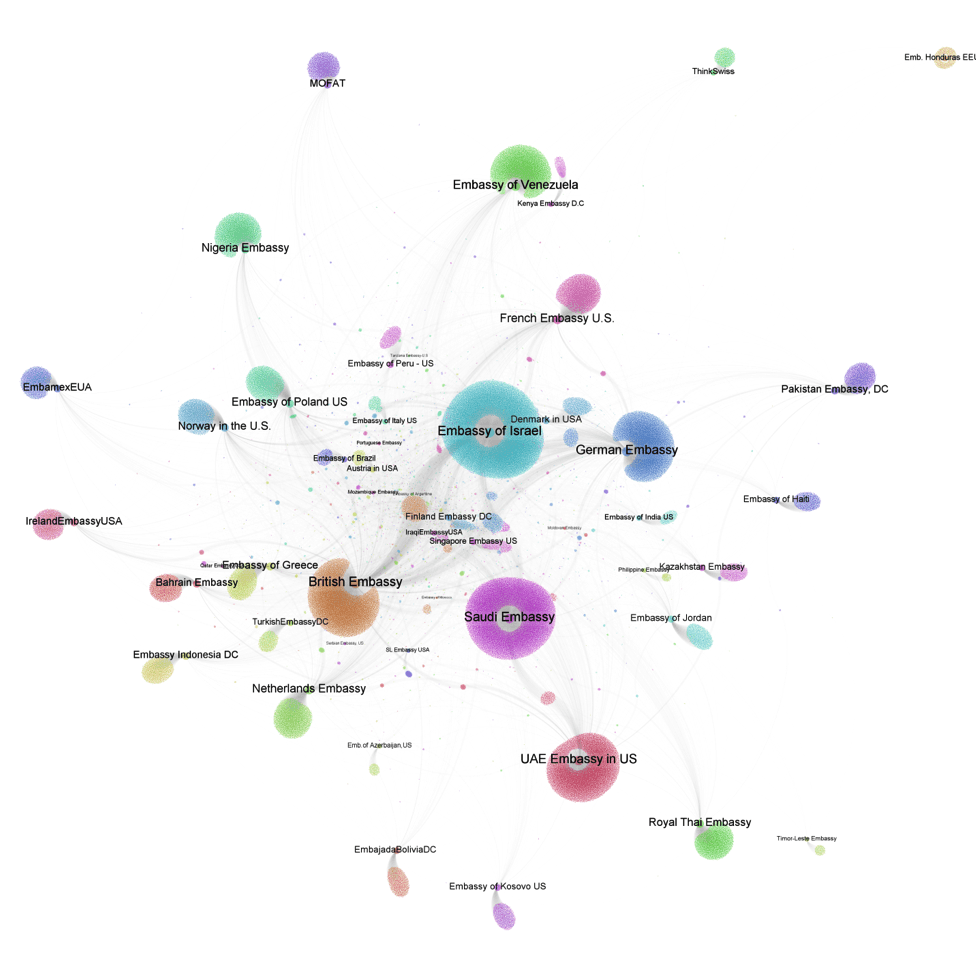

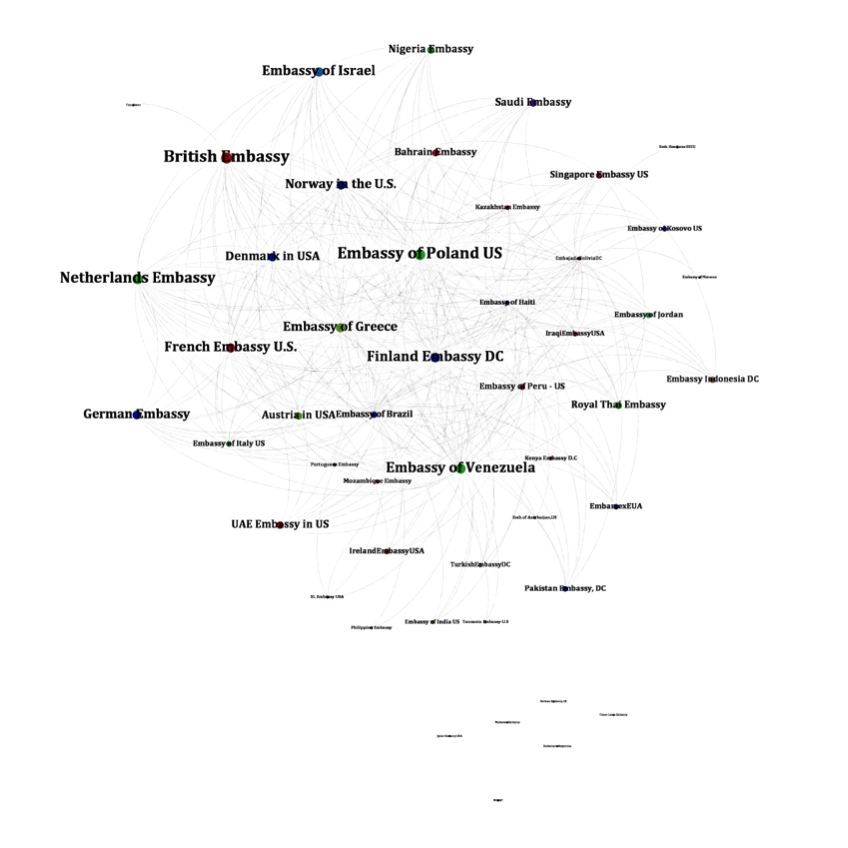

From this perspective, a very low level collaborative approach to public diplomacy could be to follow other Embassies on Twitter. The following graph represents the e-diplomacy network which exists between Embassies which are active on social media in Washington DC. Lines between nodes represent the follower / following relationships between Embassies in DC. Those represented by larger nodes and with larger labels are followed by the greatest number of other embassies in DC, and the smallest nodes are followed by the fewest embassies.

The data represented in this graph shows which embassies are considered important to follow by other Embassies. In simple terms, being followed by the greatest number of other Embassies could be a measure of importance. An alternative, Eigenvector centrality, provides a slightly more complex method of calculating importance within a network. This method gives greater value to connections from other important nodes than an equal number of connections from less important nodes. Using this method, the top ten influential embassies, amongst other DC based embassies, are shown below.

- British Embassy

- Embassy of Poland US

- Netherlands Embassy

- Finland Embassy DC

- Embassy of Israel

- French Embassy U.S.

- German Embassy

- Embassy of Greece

- Embassy of Venezuela

- Norway in the U.S.

For those seeking to collaborate with other embassies, or develop strategies to engage the diplomatic community in DC this may be a useful starting point.

In addition to the relationships with other embassies, the Twitter data allows us to analyze all the users who choose to follow the Embassies in DC that have Twitter accounts.

The above picture shows the network created by individuals following different embassy accounts. The larger the circle, the more followers the account has. The lines connecting the nodes show the number of people that follow both the accounts on each side of the line. As seen in the graphic, the Embassy of Israel, the British Embassy, the Saudi Embassy, the UAE Embassy and the German Embassy are the top five embassies followed in this network. This graphic gives us a tangible idea of just how everyone is connected in the social media world which often seems abstract and difficult to comprehend.

Group of followers that follow more than 10 embassies

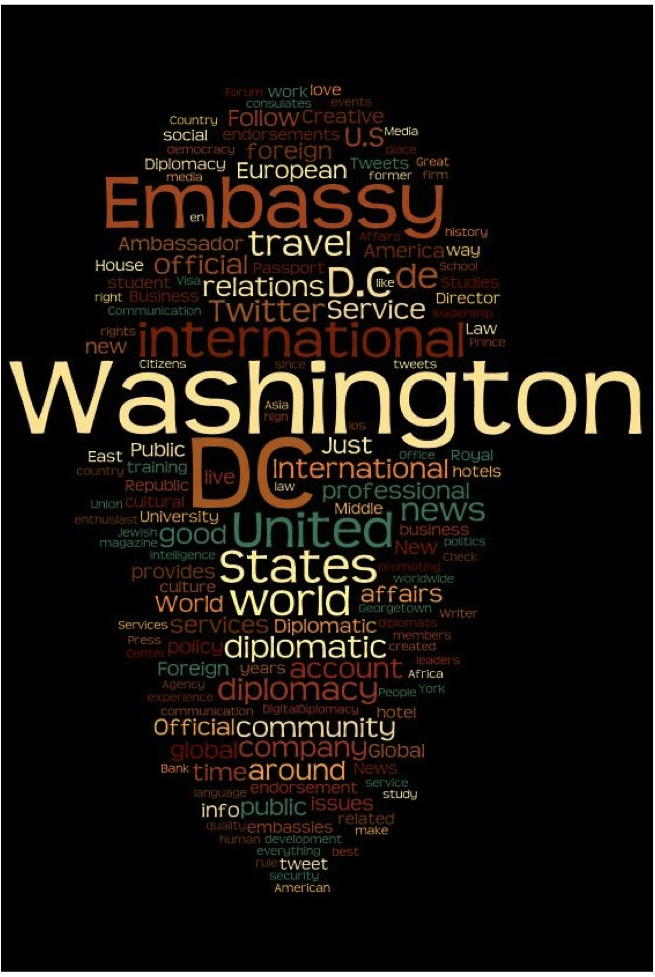

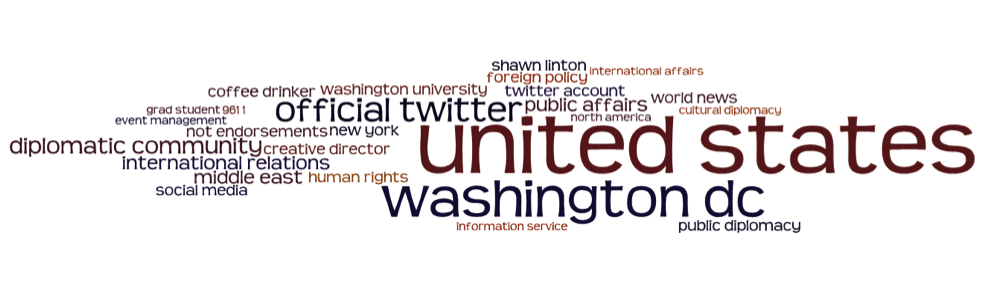

Within this network of followers, there are approximately 280 Twitter accounts that follow more than 10 embassies. Looking at this group, we can make some observations about who follows embassies. Of these 280, 22 are embassy-affiliated accounts, 13 are diplomacy non-profits and media outlets such as Meridian International and the Diplomatic Courier, and 65 of the accounts are for hotels, passport services, and strategic communications firms that would be of service to diplomats and embassies. There are also 10 accounts from users who work in the diplomatic community and 8 accounts of students studying international affairs and related fields. Glancing at the profile data of this group, we can see that the majority of these accounts are based in Washington, DC and are interested in international affairs and diplomacy. A Wordle (right) shows the most popular words in the profile data. Put in the context of a two word semantic concept wordle, some familiar phrases appear – some coffee drinkers and grad students appear alongside the diplomatic community, international affairs cultural diplomacy and foreign policy.

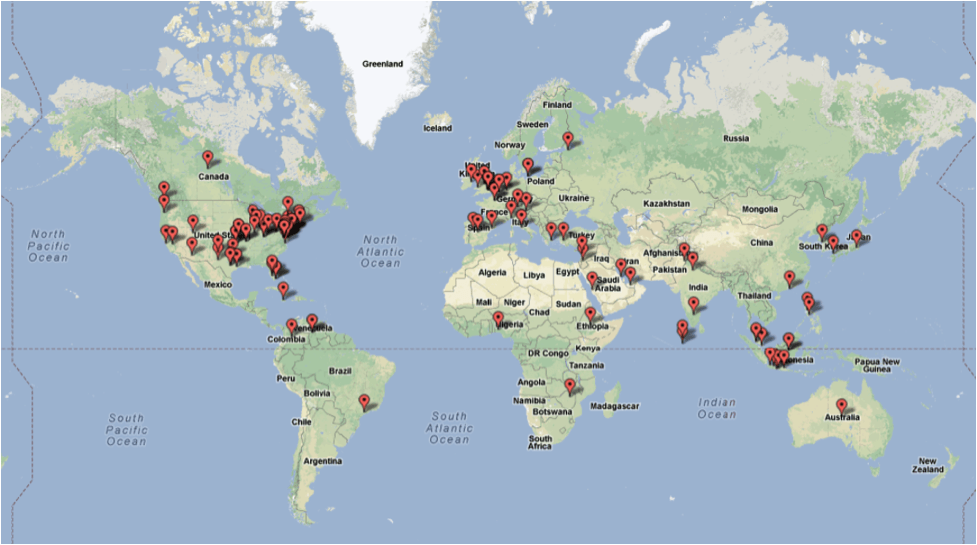

The stated location of users who follow more than ten embassies provides another perspective. Washington DC is the most common location, but as the image below shows, users following more than 10 embassies claim to be located across the world. This speaks to one of the key challenges for any embassy engaged in e-diplomacy – How to optimize their engagement when their remit is frequently focused within geographic boundaries but the uses with which they engage are spread beyond those boarders.

So What Does This All Mean?

In the first post we saw which embassies were using social media. In this post we have identified those with which embassies engage, providing information which could be useful in development of e-diplomacy strategy and, if gathered over time, evaluation.

First, we asked how many users embassies engage and looked at which the most followers. Knowing the number of followers of an account, by itself, is relatively low value tactical data. However, the comparison with other accounts in a similar position or fulfilling a similar role can at least give some context to the number.

Second, we have looked at those accounts run by embassies which are followed by the accounts of other embassies. When an embassy creates its list of priorities, the individual responsible for managing the Twitter account at another embassy may not initially be considered a key individual with which to engage. However, these embassy accounts can act as reach multipliers, facilitating the flow of information to users with an interest in international affairs (and related fields). As a result, building relationships with the other embassies via social media can allow both embassies to benefit from collaboration rather than adopting a competitive stance toward other.

Third, we looked at the extent to which followers of one Embassy account also followed other the accounts run by other embassies. Most individuals followed only one embassy, emphasizing the importance of the collaborative strategy above as a way of multiplying reaching. Their state location, along with one and two word, word clouds highlights the profile of those following ten or more embassies. Embassies may consider some of these groups or individuals as users to engage more frequently online or offline, where there is, for example, a common area of interest. This is not to say all these individuals that have shown some form of affiliation or affinity with the diplomatic community would be appropriate for all Embassies nor that embassies should charge ahead without further consideration of who they are engaging. It merely highlights that these individuals have expressed a specific interest and an embassy may benefit from further engagement activity or collaboration (online or offline) with some of these social media users.

Those familiar with Twitter know that the amount of messages or links tweeted can be overwhelming depending on how many people a user follows and how often those accounts tweet. As a result, data on followers is very interesting data that shows us how people are connected on Twitter, but still leaves some questions to be answered.

For example,

- Do the people that follow each other actually interact or is it simply a matter of following?

- Are followers impacted by the messages from the people they follow?

- Are followers actually even reading anything that is tweeted from these accounts?

- Would it have greater meaning to consider only information that is re-tweeted or contains an @mention, as these at least indicate a level of interaction (however small)?

- How can the activity of an embassy be analyzed across multiple platforms?

A lot of the messaging is probably missed and the probability of interaction between embassies and their followers is slim as people generally do not tweet directly at the embassy, and even if they do, the chance that the embassy tweets back and starts a conversation is slim based on a quick glance of the most recent tweets from each of the embassy accounts.

This type of disruptive metric is becoming an increasingly important part of diplomacy, through both strategy and evaluation. There is still a lot of research to be done regarding impact and strategy, but the above observations provide a basic landscape through which to understand how the platform is being used by those working in Washington DC. Further research will delve into the activities of a few specific countries across multiple platforms.

On January 5-6, while India and Pakistan faced each other on the cricket pitch, teams of exchange program alumni from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh engaged in

On January 5-6, while India and Pakistan faced each other on the cricket pitch, teams of exchange program alumni from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh engaged in  secured the first live phone interview with a Malawian president as a result of his U.S. program experience. In his words: “one thing I learned while covering the elections is that the American President is always scrutinized by the public. Immediately I arrived home I got in touch with our ‘White House’ to have the President answer questions from the public. I am proud to announce that on December 31, I was the first Malawian journalist to have a live phone interview with the President where people posed questions to [him], a thing that has never happened before in my country.”

secured the first live phone interview with a Malawian president as a result of his U.S. program experience. In his words: “one thing I learned while covering the elections is that the American President is always scrutinized by the public. Immediately I arrived home I got in touch with our ‘White House’ to have the President answer questions from the public. I am proud to announce that on December 31, I was the first Malawian journalist to have a live phone interview with the President where people posed questions to [him], a thing that has never happened before in my country.” Jerusalem: The board game Monopoly has proven a potent tool in fostering the entrepreneurial spirit among Palestinian youth, while simultaneously introducing a mainstay of American culture.

Jerusalem: The board game Monopoly has proven a potent tool in fostering the entrepreneurial spirit among Palestinian youth, while simultaneously introducing a mainstay of American culture.  In the lead-up to the U.S. Presidential Inauguration, Consulate Hong Kong began a social media project that included photos, videos and travelling cardboard cutouts of President Obama and the First Lady.

In the lead-up to the U.S. Presidential Inauguration, Consulate Hong Kong began a social media project that included photos, videos and travelling cardboard cutouts of President Obama and the First Lady.  The U.S. Consul General in Munich spoke to students and faculty of “Berufsschule 4,” an off-the-beaten-track school in Nuremberg. He addressed U.S.-German relations, the U.S. presence in Bavaria, and economic and commercial ties, and tackled tough questions about car emissions, Guantanamo, gun control, and social media topics. The

The U.S. Consul General in Munich spoke to students and faculty of “Berufsschule 4,” an off-the-beaten-track school in Nuremberg. He addressed U.S.-German relations, the U.S. presence in Bavaria, and economic and commercial ties, and tackled tough questions about car emissions, Guantanamo, gun control, and social media topics. The