U.S. public diplomacy campaigns can be even further enriched by integrating advertising audience targeting and engagement tactics into the existing diplomatic digital and social media strategy and execution. Tapping into these tactics will build on the strong foundation that is already set in the social media landscape by the U.S. Department of State in their current digital diplomacy strategy.

Certain online audience targeting tactics come to mind when reviewing current Embassy social media content. Digital diplomacy messages shared by the numerous U.S. Embassy accounts can be boosted with compelling visuals. Several posts contain visuals automatically selected by the Facebook algorithm from the website the U.S. Embassy is sharing in the post. These click through links all direct the audience to a Department of State website, and thus the visuals belong to the Department as well. The U.S. Embassy should consider uploading the visuals as part of the post directly, as the Facebook algorithm frequently does not select the best visual from the click through link for the purpose of the post. Selecting the visual and uploading it directly will give the U.S. Embassy the greatest amount of control with respect to what information the team is emphasizing to the audience. Posts with such visuals, whether photos, infographics or graphs, are proven to perform at higher engagement rates, no matter the industry, and the Embassies should share content with such compelling visuals in order to work on securing higher levels of engagement.

Next, a call to action (i.e. Learn More, Discover the United States, See Additional Photos, etc.) will naturally entice the audience to click through to the links provided and engage further with the content from the U.S. Government. The links should direct the audiences to more detailed information of the official position on the topics at hand. This is an opportunity to expand upon the content shared in a limited 140-character tweet or short Facebook post, and every effort must be made to motivate the audience to click on the link to continue the engagement past the initial post.

Finally, using varied language, or copy, with wording closely aligned to the Embassy’s goals and target audiences will speak volumes. While I am not in a position to know the exact target audiences of the Embassies, I take issue with the catchall approach the social content currently seems to employ. A foreign population is a challenging audience, and it would serve my presumed goal for the Embassy of increased engagement with social media content to segment and more specifically target the desired audiences. Several desired audiences that the Embassies might want to target in their communications include the educators, students, law makers/politicians, elites or societal influencers, and the general population of the country where the Embassy is hosted. Engagement happens when a member of the target audience is inspired by the message to respond. Doors open when strategies and tactics are used to speak directly to that target audience as opposed to an entire population.

Our U.S. Embassies around the world shared relevant and detailed information leading up to the historic U.S. Election in 2016 across their social media channels. Take the U.S. Embassy in South Africa as an example – several Facebook posts were publicly shared to explain more about the Electoral College, election vernacular, and voter fraud potential. These topics are all of interest to South Africans, particularly with the recent South African Municipal Election still fresh in their minds. Yet, this outsider believes the messages could be even further refined and targeted to different but equally important audiences for the U.S. Embassy, such as the lawmakers or the educators in country. Reworking the content in these posts is a relatively straightforward process, and one that can be easily incorporated into the ever-expanding analytics and graphics group at the Department of State.

The Embassy’s post about the Electoral College aims to share important information about the essential process by which the U.S. President is chosen. Unfortunately, the Facebook post has little energy and direction for the audience to grasp, particularly with the use of quote marks, which invite speculation into the interpretation of the statement.

Figure 1: Screenshot of U.S. Embassy South Africa Facebook post on November 8, 2016, captured on November 22, 2016 3:45PM ET

The leading question used in this post can be built upon by using more specific and varied language to align the post with the intention of reaching a certain target audience. Audiences need to be spoken to directly with appropriate vernacular and thought-provoking issues to entice engagement and understanding. The Embassy could rework the post to say, “Why does California have more Electoral College votes than Alaska? The Electoral College is at the heart of our democratic voting process, yet most Americans still need a refresher on the puts and takes of the system. Take a look at this post to gain deeper insight into the inner workings of American voting this election season: [link]” in order to accommodate this recommendation when looking to engage with a general population of local South Africans.

Secondly, this post’s image was selected by the Facebook algorithm from the link shared. It is a superb photo to use in the post – the iconic New York Rockefeller Center ice skating rink with the red Republican and blue Democrat map of the United States is a captivating visual for those interesting in learning more about the United States. However, this photo can be further emphasized by use of the direct image upload feature on Facebook to show the full visual and share an intentional emphasis of the photo.

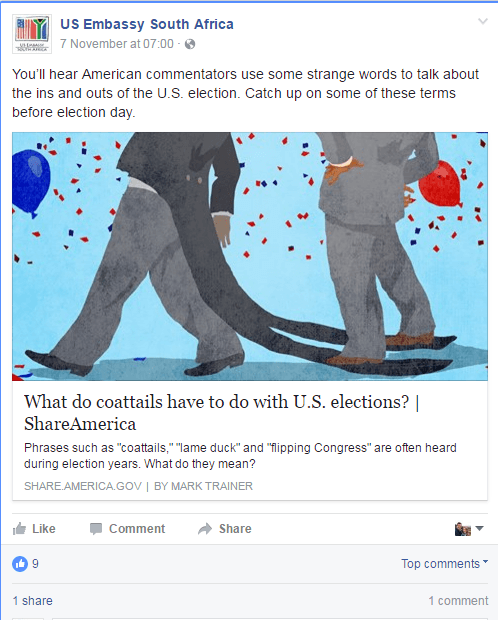

A second post by the U.S. Embassy in South Africa focused on the use of election vernacular and how foreign audiences should interpret the meanings of those terms within the context of the U.S. General Election.

Figure 2: Screenshot of U.S. Embassy South Africa Facebook post on November 7, 2016, captured on November 22, 2016 3:45PM ET

Again, the “coattails” visual contained in this post is dynamic and illustrative of the topic at hand, but the viewer is unable to enjoy the full effect as only two-thirds of the image is shown. By uploading the image directly into the post, the audience sees the entire image, including the full politicians with the election confetti and balloons, and knows that the visual directly corresponds to the post content.

Additionally, the topic of United States election vernacular could be an enjoyable educational experience, particularly for the audience of South African government workers and educators alike, yet the copy used in the second part of the post is devoid of excitement. The language is stiff in the opening sentence “You’ll hear American commentators use some strange words to talk about the ins and outs of the U.S. election,” as if it is being held back behind a wall that only cautious, appropriate copy is allowed to pass through. Injecting additional punctuation, adjectives and calls to action will jazz up the language and entice more readers to stop and read the post, and then perhaps even engage with the post to learn more. Careful selection of this language is of course required, but even a simple “Take a glance at this quick guide to the three most common phrases used by Americans around Election Day: [link]” would help to encourage additional engagement with the Embassy post, particularly with an elite or political audience short on time and needing a quick update on the latest U.S. Election slang.

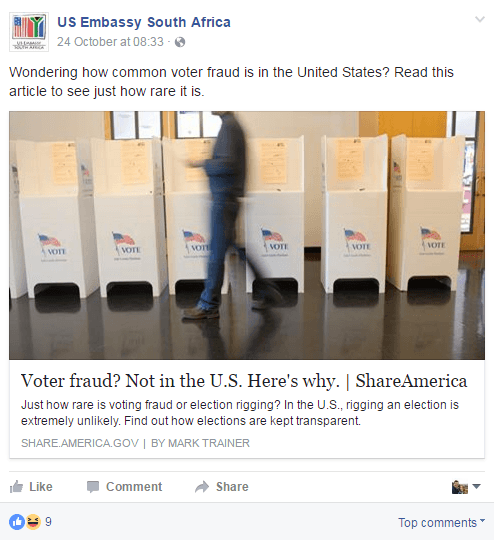

Finally, the third post I’ve selected from the U.S. Embassy in South Africa’s Facebook page centered on the potential for voter fraud.

Figure 3: Screenshot of U.S. Embassy South Africa Facebook post on October 24, 2016, captured on November 22, 2016 3:45PM ET

This post is perhaps the most in line with the recommendations I suggest for further enhancing the effectiveness of the posts. The language is more intriguing to the South African audience, given the direct connection to the current discussion revolving around fraud in South African government, and includes a direct call to action to read the article by clicking on the link to learn more.

All of these U.S. Embassy South Africa posts use click-throughs to the Share.America.gov, a website populated with State Department content which is “the U.S. Department of State’s platform for sharing compelling stories and images that spark discussion and debate on important topics like democracy, freedom of expression, innovation, entrepreneurship, education, and the role of civil society.”[1] This platform is an excellent representation of a dynamic, mobile-optimized website where the audience can expand their knowledge about official policy positions and current actions taken by the U.S. Government on the topics of the posts.

These three tactical approaches to refining social media content directly correlate to the strategy of furthering engagement with local populations and improving retention of U.S. policy positions. Each tactic can be further supplemented with the use of paid promoted posts in the social media platforms. A relatively small amount of dollars can go a long way to specify the audiences targeted by each message execution (certainly when compared to the cost of an exchange program or speaking tour, for example). The greatest measurements that would clearly portray an improvement in Embassy posts are engagement rates, impression numbers, click through measurements and the like, all of which are only available to the individual account managers and not this outsider. I urge the Department of State to consider these ideas in order to implement upgrades that further enhance audience targeting, segmentation, and resulting engagement throughout their online diplomatic strategy, including both paid and non-paid options.

The views expressed within are solely the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of George Washington University.

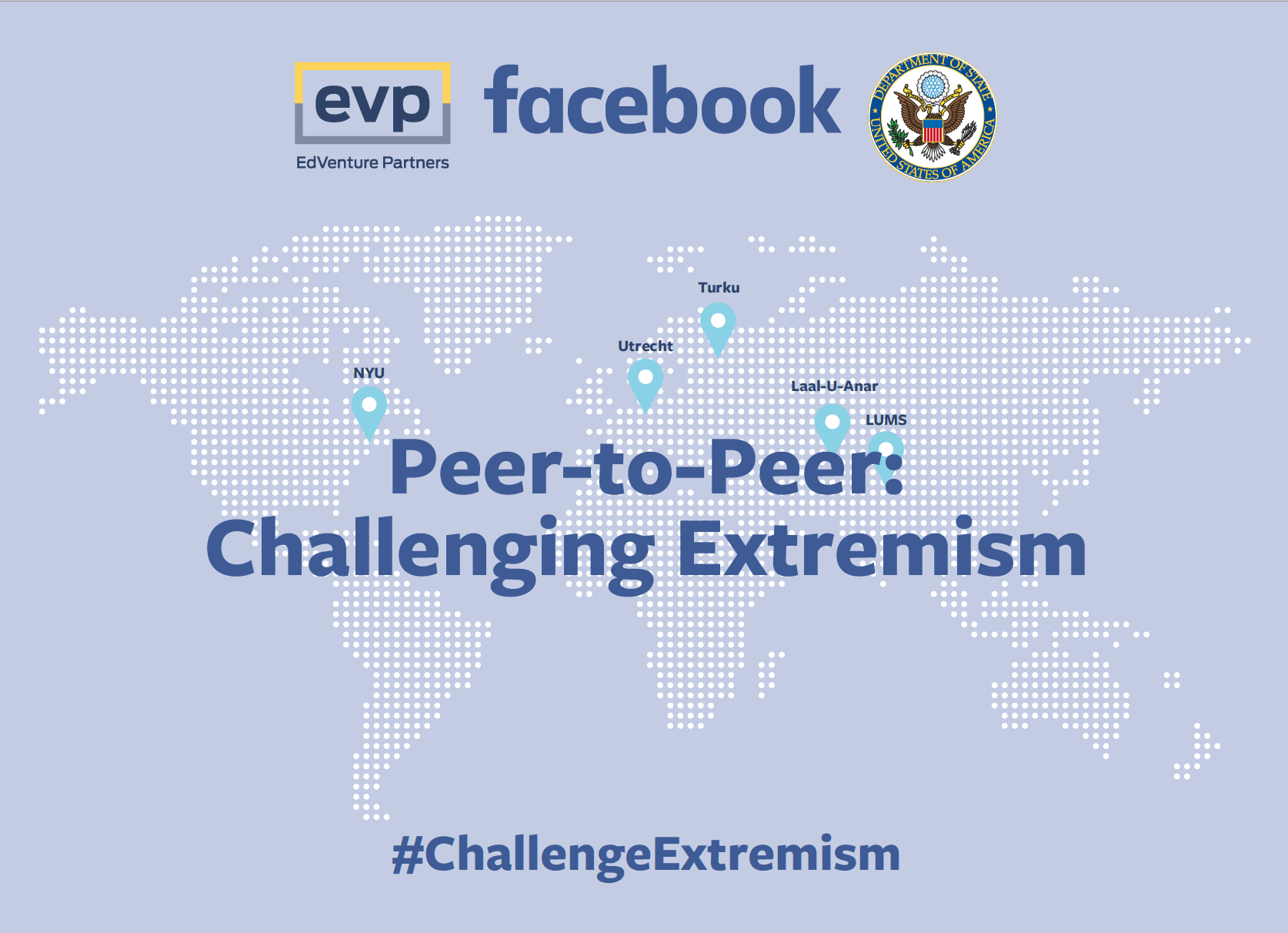

The U.S. State Department has developed several programs, which have revolutionized traditional diplomacy; among them is

The U.S. State Department has developed several programs, which have revolutionized traditional diplomacy; among them is