By Jenna Presta, BA in Political Communication ’19, MA in Media & Strategic Communication ‘21

In the 1990s, the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia declared their independence and intentions to secede from Georgia. Neither of these territories is widely internationally recognized as an independent state. However, in 2008 Russia moved troops into the regions, declaring them to be independent. Georgia, backed by most Western nations, declared Abkhazia and South Ossetia to be occupied territories. Russia’s destabilizing moves point to more than a display of dominance. They have consequences for Georgia’s larger place in the international system and its identity as a nation. These are shaped by and build upon strategic narratives.

There are several layers of narratives that grant this territorial standoff a greater meaning. Narratives are the frameworks by which we understand the world around us. When it comes to international affairs, narratives can describe and shape a particular issue, the identity of a nation, or even the international system itself. These all help to shape and explain Georgia’s resistance to Russia’s occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Also relevant to this issue are master narratives, which are those embedded within the historical memory of a nation or people. Master narratives do not have to be taught; they are passed down through a culture. Two of Georgia’s most salient master narratives are (1) the struggle for sovereignty against an imperial power and (2) the rebirth of Georgia as an independent, self-governing state. These narratives often operate in tandem; rebirth following struggle. These master narratives explain why Georgians perceive Russia’s presence within its internationally recognized borders as a continuation of the historical aggression the Georgian state has experienced from Russia and the Soviet Union. Georgia’s historical memory catalogues the occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as an affront to its sovereignty, rendering Russian narratives ineffectual.

This perspective feeds into Georgian identity narratives, which are those that describe Georgia’s identity as a country. These identity narratives depict Georgia as a strong, independent, and unified state which governs itself. Identity narratives can also constrain a nation’s behavior. Georgia, for example, values self-governance and is a nascent democracy, and thus is expected to behave as such. Additionally, Georgian nationalism has become increasingly important since it seceded from the Soviet Union in the 1991 referendum. This helps to explain why Georgia views the Abkhazia and South Ossetia controversy as an occupation of their territories, rather than accepting Russia’s narrative of support for independent states.

This perspective feeds into Georgian identity narratives, which are those that describe Georgia’s identity as a country. These identity narratives depict Georgia as a strong, independent, and unified state which governs itself. Identity narratives can also constrain a nation’s behavior. Georgia, for example, values self-governance and is a nascent democracy, and thus is expected to behave as such. Additionally, Georgian nationalism has become increasingly important since it seceded from the Soviet Union in the 1991 referendum. This helps to explain why Georgia views the Abkhazia and South Ossetia controversy as an occupation of their territories, rather than accepting Russia’s narrative of support for independent states.

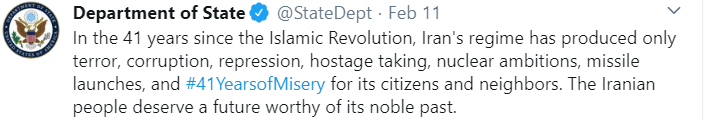

Narratives related to the international system are especially important in this situation as they demonstrate the aforementioned line between “occupation” and “independent states.” Georgia and most of the West have invested in narratives which demonstrate the importance of international institutions. They argue that the international community should be the forum for recognizing nations, and that, therefore, Russia’s occupation of Georgian territory violates international norms. This further influences the perspective of Georgians by characterizing Russia’s moves as an infringement, thereby decreasing the power of their narratives. These separate narratives all come together to emphasize the sovereignty and independence of Georgia as a self-governing state, in turn shaping Georgia’s – and most of the West’s – response to Russian troops in Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

This situation further impacts Georgia’s larger place in the international system. As a relatively young democracy, Georgia is seen by many as torn between allying itself with the West and with Russia/Eurasia. Where Georgia chooses to align itself has real consequences, as narratives do shape and constrain behavior. A Georgia in a Western alliance may behave quite differently than a Georgia in a Russian alliance. In the fight for Georgia’s allegiance and national identity, Russia attempts to cast a shadow on partnership with the West in order to bring Georgia into the sunlight of a Eurasian bloc. Its presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia is supported by propaganda campaigns asserting that aligning with the EU, US, or NATO will corrupt the traditions and identity of Georgia as a state. This taps into narratives related to Georgian nationalism, sovereignty and independence to create an overwhelmingly negative picture of a Western Georgia.

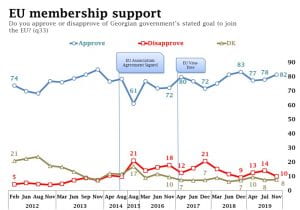

Despite these efforts, polling data collected by NDI shows that the overwhelming majority of Georgians do support EU and NATO membership. This could point to the salience of the Georgian narratives I’ve described here. Russian propaganda efforts do not seem to be enough to override Georgia’s historical memory, or its vision of itself as a sovereign nation that is part of a greater system. It is clear how the various narratives surrounding Russia’s presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia feed into a larger picture of Georgia’s place in international affairs – and vice versa.

> The author has also written a case study of the battle of narratives over Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

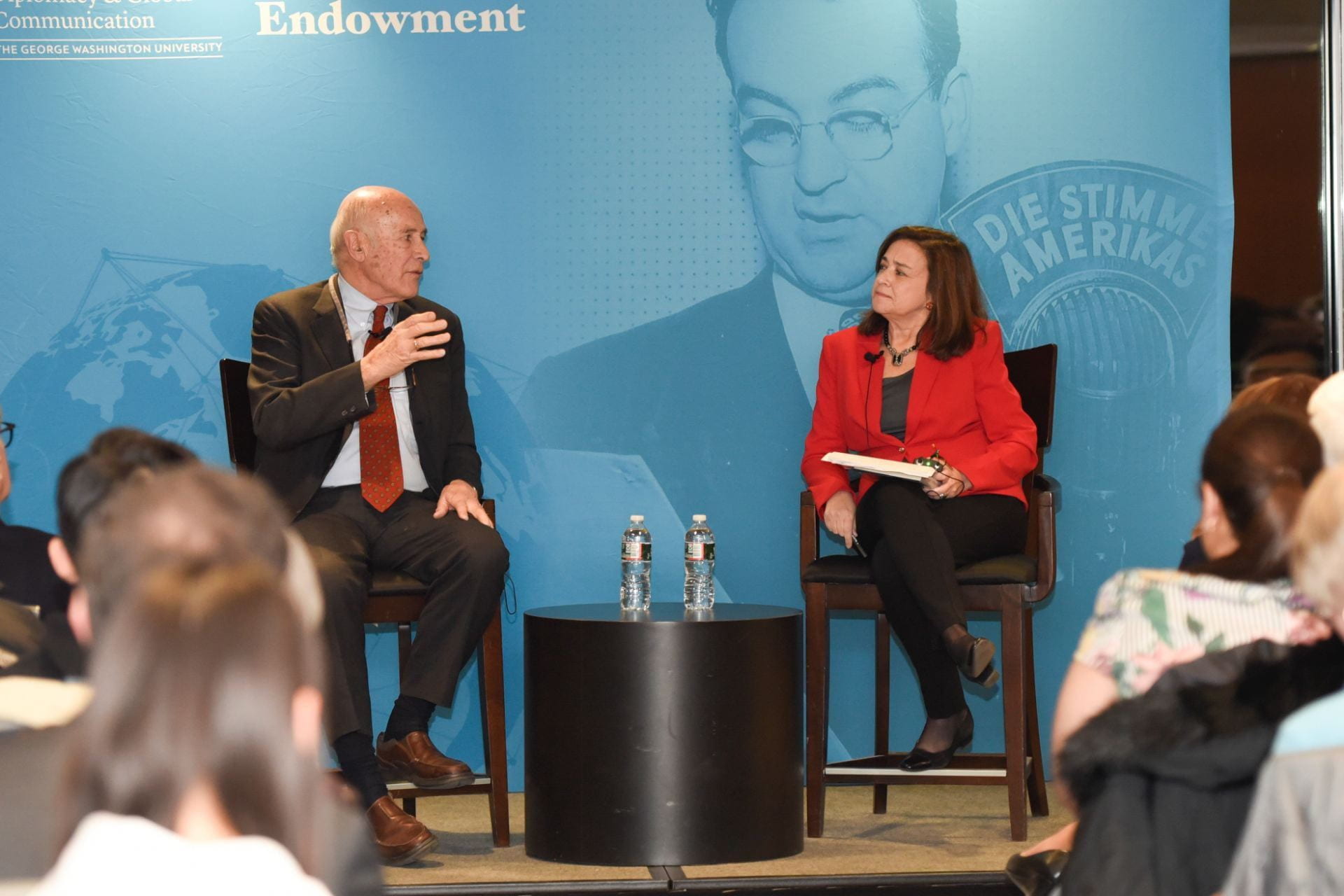

Public Diplomacy Fellow Emilia A. Puma had a great conversation with SMPA Undergraduates Jason Katz and Sarah Schornstein about her career in the U.S. Foreign Service. As a 28-year veteran, Prof Puma talked about her work – most recently as Acting DAS for Public Diplomacy and Central Asian Affairs in the South and Central Asian Affairs Bureau and also Foreign Policy Advisor to the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force (CSAF) among others.

Public Diplomacy Fellow Emilia A. Puma had a great conversation with SMPA Undergraduates Jason Katz and Sarah Schornstein about her career in the U.S. Foreign Service. As a 28-year veteran, Prof Puma talked about her work – most recently as Acting DAS for Public Diplomacy and Central Asian Affairs in the South and Central Asian Affairs Bureau and also Foreign Policy Advisor to the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force (CSAF) among others.