I propose a stronger media campaign in the Arab world that works to counteract the Trump effect by providing viewers with context and content. This media campaign may prevent future radicalization against America by showing that Trump doesn’t represent the entire country or the government. We need to reach American Muslims and the Arab world to block ISIL recruits. ISIL has a great strategic media plan making them appear sympathetic in comparison to Trump, so we need one too.

First, the program should explain the context of Trump’s primary election campaign. In American politics, candidates play to the base to distinguish themselves during primaries. We should explain this to the foreign audience and help them understand why Trump is taking such radical positions. Votesmart has an educational fact sheet about American primaries that is easy to understand. We could provide an info-graphic with all this information. I believe an info-graphic is the best form because they get the most likes, shares, and clicks on social media. An info-graphic can be easily tweeted out or shared with other followers.

But we should follow up with a brief history of American primaries, providing specific examples. The 2012 Republican primary was at times a contest of which candidate could be the most conservative. Or in 2008, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama battled for who was the most liberal. This shows that 2016 isn’t the first election where rhetoric was more extreme in the primary than in the general election. We could even create a short documentary about it, with guest appearances from people they like in the region. We could also have a media cite, like a blog page or social media account, where we frequently put out entertaining content that sneaks in the political themes. For example, people love memes and gifs. We could post them with a political slant, that way we get more views while still sneaking in the political message.

Second, we provide polling data to prove that most Americans don’t support Donald Trump or his policies. Currently, 70% of Americans find Trump unfavorable when asked in the context of the Presidential election. When asked about Trump, the businessman from New York, still 68% of Americans find him unfavorable. When broken down by party, 62% of Republicans favor him while 31% don’t. 13% of Democrats find him favorable, while 84% unfavorable. And for Independents, 34% find him favorable and 59% unfavorable. This means the majority of Americans do not support Donald Trump. 61% of Americans say he is hurting the Republican Party.

Most Americans also do not support Trump’s policies. When asked about the complete ban on Muslims, 63% of Americans said this was the wrong thing to do. They felt it was morally wrong and against the American values of inclusion and diversity. 62% of Americans also oppose building a wall on the border of Mexico. Finally, 54% of Americans say the Republican Party is too extreme and 65% say they are intolerant. These statistics prove that most Americans are not intolerant or anti-Arab. We could provide these statistics in the form of info-graphics on social media. This way they will get the most views and people can share them with their followers.

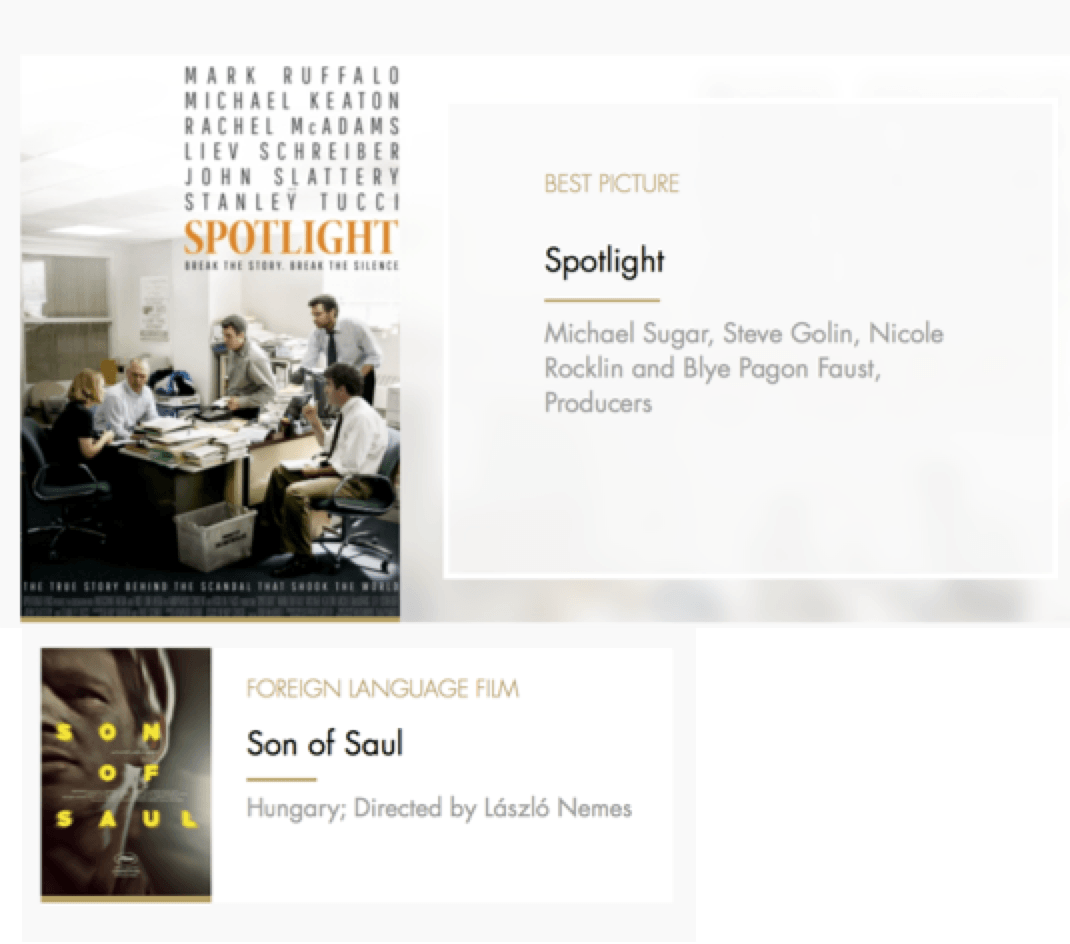

Finally, we should attempt to show America in the best light, without lying or tarnishing our credibility. This includes citing our history of inclusion, diversity and equality. We could show movies and other American media that depict this history, providing the necessary content in an entertaining way. For example, movies like Selma and Freeheld that recently came out would be perfect. Also, interracial relationships show that America is not racist or intolerant. Interracial relationships have spiked in recent years and are only increasing. Statistics and shows that include these relationships like Modern Family, Blackish, and Scandal can show viewers that America is inclusive of all colors. Exposing them to our positive media, while creating more targeted audience specific content, is an excellent strategy.

This is how we combat ISIL, not only through military conflict and drones, but also through soft power and influence. Right now Trump is negatively influencing the region through his offensive outbursts in the media, so America needs to strategically counteract the Trump effect to prevent future radicalization.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication.