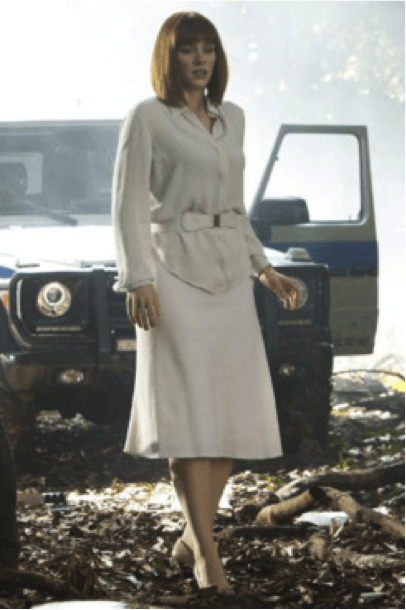

In Jurassic World, the second-highest grossing film worldwide in 2015, Bryce Dallas Howard plays dinosaur theme park manager Claire Dearing, who treks across the park’s island in white silk skirt-suits and nude patent leather pumps. Dearing comes to represent women’s characterizations at their worst, not just because of her impractical clothing choices but her character traits—she is emotionally distant, professionally incompetent, and when the island is in trouble she defers to the muscular and conventionally-masculine Owen Grady (played by Chris Pratt) for help. As Vulture columnist Jada Yuan notes, although Claire eventually saves Owen and her visiting nephews, she’s still undermined by her relationship with Owen and her overall lack of depth as a character.

It would be easy to write off Jurassic Park as an unfortunate anomaly, as a portrayal that may have missed the mark but was one of many diverse portrayals of women. However, that’s not the case—a 2012 study done by the USC Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism examined five years of Hollywood films and found that female characters were both underrepresented and oversexualized. These findings were confirmed again in a study of the top 100 films of 2015. The Annenberg study found many films just like Jurassic Park: women made up less than a third of all speaking characters, but when they were portrayed, 31.6% of the time it was in sexually revealing clothing.

While these gratuitous portrayals of women are certainly damaging to American ideas of femininity, Hollywood portrayals of women don’t just affect domestic audiences. In fact, over half of total box office revenue now comes from non-American international audiences, and as Martha Bayles writes, our movies affect how foreign audiences perceive America.

Bayles posits that Hollywood has always been an important tool of public diplomacy, deeply influential in shaping foreigners’ perceptions of America. In Through a Screen Darkly: Popular Culture, Public Diplomacy, and America’s Image Abroad, she traces Hollywood’s pact with Washington back decades. In a 1944 memo to the Motion Pictures Association of America, the State Department wrote that it would protect American films abroad, so long as “the industry will cooperate wholeheartedly with the government…ensuring that the pictures distributed abroad will reflect credit on the good name and reputation of this country and its institutions.” Washington knew early on that Hollywood was shaping foreigners’ perceptions of America, and this is still true today.

However, Washington now faces a crisis if Hollywood is determined to continue portraying women in a trivializing and sexualized manner. The State Department has prioritized programs that advance the status of women and girls, from the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Women Entrepreneurship Program (which creates partnerships through the private and public sectors in the Middle East and Northern Africa focused on inclusive economic growth) to the countless exchange programs that empower women and girls through sports, education, mentorship, and the arts. But if these same women and girls are also getting their cues about women’s roles from Hollywood, how credible can America claim to be when it comes to the full equality of women and girls?

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YNyKc5mP4yM]

[Video: Goldman Sachs 10,000 Women Entrepreneurship Program, US Department of State]

Bayles’ research confirms that the American export of popular culture is, at this point in time, damaging our image abroad. Global opinion polls find foreigners rejecting both the “pervasiveness” and the “coarsening” of American popular culture, and our portrayal of sex and gender roles is examined with an especially close lens. Bayles writes that foreigners take depictions of gender roles at “face value,” not understanding that sex and gender roles are often distorted and played for laughs or for social critique. This ought to be of paramount concern for American practitioners of public diplomacy, who desire for America to be seen as a leader on women’s issues.

What role, then, can public diplomacy play when Hollywood is perpetuating these harmful stereotypes? Certainly it is not Washington’s place to censor American popular culture. However, there are positive portrayals of women that the State Department can boost, showing foreign audiences what empowered and non-sexualized women look like. Films like 2015’s The Martian, where women scientists are seen working professionally to save their stranded colleague, should be included in cultural programming and highlighted as examples of gender equality.

Ultimately, the power to change women’s portrayals in film rests with Hollywood. One finding from the 2012 Annenberg study that could be cause for optimism is that when women are placed in key creative roles in films, overall portrayals of women increase while sexualized portrayals of women decrease. Practitioners of public diplomacy can help place public pressure on the film industry and include women filmmakers and creators in cultural programming. It is only through increased awareness and rewarding positive work that public diplomacy can help reverse the effects of women’s negative portrayals in film.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication.