Organizations in the international development sector are increasingly focused on external communications efforts in addition to the activities that support their mission. These organizations, whether government related or not, work to remedy conditions they find problematic, which are usually complex, transnational issues, such as poverty, inequality, or HIV. It as become increasingly important for these organizations to frame information in a way as to create a sense of necessity and urgency in order to convey their messaging and gain support for projects and initiatives.

Framing involves highlighting certain aspects of a story in order to promote a particular view. The four steps to framing, as outlined by political communications scholar Robert Entman, are:

- Defining effects or conditions as problematic

- Identifying causes

- Conveying moral judgment of those in the framed matter

- Endorsing remedies or improvements to the problematic situation.

Research shows that visual elements, such as photos and videos, are better at communicating messaging and evoking emotional responses in audiences than text alone. Not only do visuals help to tell a story, but they also help to frame messaging. The most successful international development organizations rely heavily on the use of compelling visuals to at every step of Entman’s steps to framing. Visuals help to underscore an organization’s messaging on the conditions it deems problematic, the causes of those conditions, the organizational moral judgment of those involved and how the organization intends to improve, or is already improving upon the situation. Visuals help to emphasize the values of the organization and outcomes of their work. In an environment saturated with overlapping agendas and oftentimes indistinguishable projects, development organizations use photos, videos, and visual frames to not only tell their unique story to stakeholders and to the general public, but to also set themselves apart from other organizations in the field.

Visuals add depth and context to an NGO’s messaging and are instrumental for an organization’s ability to resonate with audiences, gain support for their cause, and prove the value of their work. Not only do visuals reinforce textual messaging, but visuals also help to convey meaning that words cannot, by tapping into the emotions of the audience. The better an organization is at convincing people on an emotional level, the more support they receive from states and citizens to conduct their activities. A development organization must be able to tug on heartstrings and express the gravity of the issues they prioritize. This is central to their success. Adding visual elements makes messaging less abstract and makes information more relatable, even to audiences that might not be aware of the subject matter.

Narratives and Visual Frames in International Development

During the recent Ebola crisis, affected countries in West Africa were painted as hopeless and destitute, with stories of death and devastation being broadcast across the globe. In an effort to convey the success of their efforts, the UN Mission for Emergency Ebola Response highlighted stories of people that had been affected by their work. In the example above, the visual adds impact to the written text. Alone, the text is somber, and makes the reader imagine a despondent Siah. With the photo, the “Ebola survivor and hero” is personified. The audience develops more of a connection with her story, because they are able to see the person being referred to and they are able to connect the efforts of the organization to a story of success. The story is not only much less abstract and more relatable, but it is also visualized and therefore more profound. The woman is smiling, underscoring the sense of hope, despite her challenges. Using the photo along with the text reinforces the messaging that the organization’s efforts are effective.

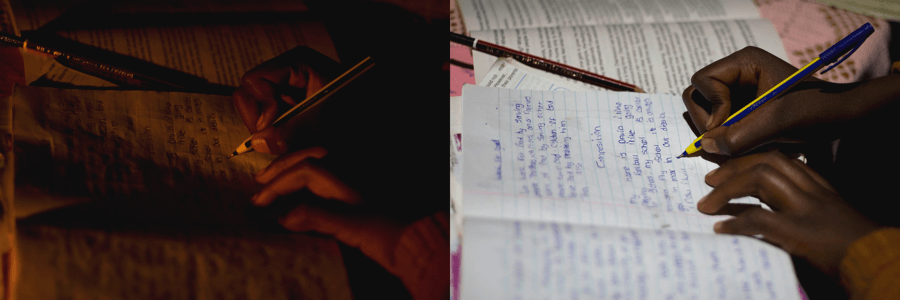

When he launched the Power Africa program in 2013, President Obama said, “Access to electricity is fundamental to opportunity in this age. It‘s the light that children study by; the energy that allows an idea to be transformed into a real business. It’s the lifeline for families to meet their most basic needs.”[i] The USAID Power Africa program aims to address the problem of lack of electricity across Africa. Many of the images used by this program, including the one above, show the difficulties of living life in the dark or by kerosene lamps or candlelight. Photos like this comparative shot convey the necessity of the program, and show the impact of their efforts, further reinforcing the narrative that access to electricity enables communities to succeed.

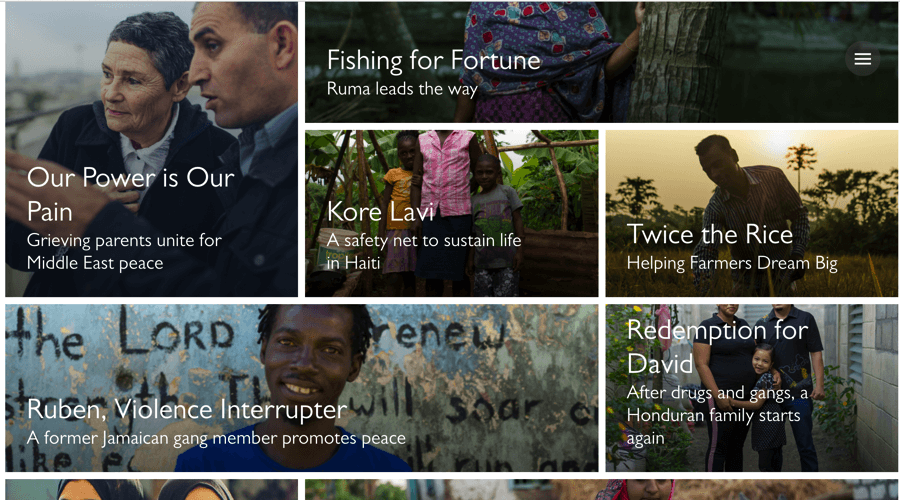

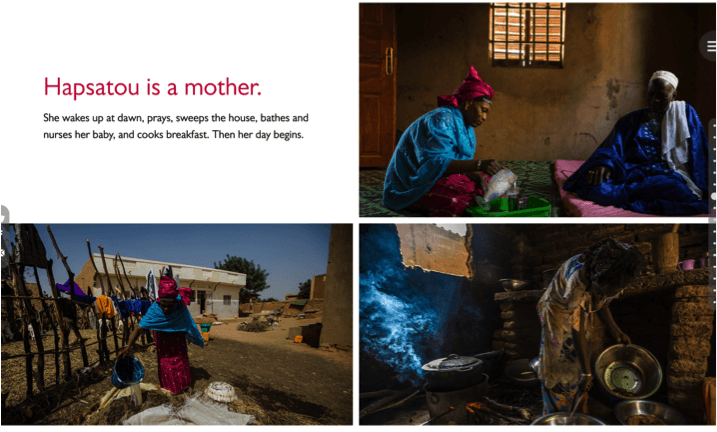

The US Agency for International Development, like many other international development organizations uses visuals to frame their messaging and highlight the impact of their work. The website stories.usaid.gov leads to dozens of visual stories that use a combination of photos and videos to highlight the impact that USAID has had in many

parts of the world across their focus areas. These visual stories have taken the place of traditional, text heavy success stories and underscore the narrative that the agency is having an impact on lives around the world. The visual stories give a more engaging overview, making the people involved more relatable and their problems and successes more imaginable. Visuals humanize the story, making it easier to influence audiences with the messaging.

International development organizations must rely more on visuals in order to communicate the need for their interventions and to prove the success of their work. By using visuals to convey messaging, these organizations are better able to win support for their causes. Visuals aid in the framing of messages, which allows them to more easily influence audiences and win support for their efforts.

[i] Barack Obama, qtd on USAID Power Africa homepage, https://www.usaid.gov/powerafrica

away a more complex understanding of their lives and the impact that FFP has had upon them, and empathize with their feelings of fear of uncertainty.

away a more complex understanding of their lives and the impact that FFP has had upon them, and empathize with their feelings of fear of uncertainty.