Saudi Arabia: Contender for Superpower State in a New World Order

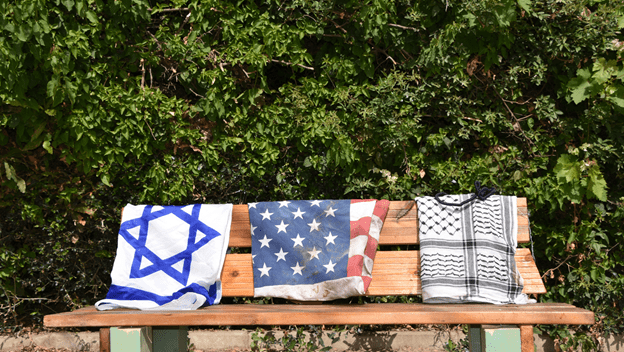

By Tahreem Alam, Masters in International Affairs ‘23 Saudi Arabia has taken key economic issues into its own hands, worrying its Westerncounterparts and prompting reactions from the Biden administration. These actions arereflected in Saudi Arabia’s oil policies, which is increasingly pursuing its own interest andoften seen at an expense to…