Movies are a very impactful and influential tool towards gaining a perspective of a culture, situation, norm, and/or environment, which is why PAOs acknowledge films as a legitimate form of cultural diplomacy. An American watching a movie taking place in Pakistan will notice norms that differ greatly from American culture, as would a Pakistani watching a film taking place in America. And through that simplistic cultural exchange, each viewer would have a better understanding of the other country. As Rhonda Zaharna mentions in her article The Cultural Awakening in Public Diplomacy, culture determines values, and movies represent culture.

So with this emphasis on movies and their impact, it’s hard to determine which film would be considered an all-encompassing “Best” film in the world. Film festivals that take place in Europe such as the Berlin International Film Festival, Cannes Film Festival, and the Venice Film Festival allow movies from all over the world to win the deserving “Best” film, actor, etc. category. The U.S., however, has only one category devoted to international films (Best Foreign Language Film) in their only film award show: The Academy Awards, or “Oscars”. The lack of international focus in film entries is representative of America’s overall lack of international perspective and interest in comparison to Europe’s.

In his article You Talkin’ to Me?, Begleiter states that Americans express an ignorance of the world by being ill informed about international politics and events, while not even caring enough to learn about them. He sees this lack of perspective as a lack of freedom, even though we pride ourselves on being the ‘freest country in the world.’

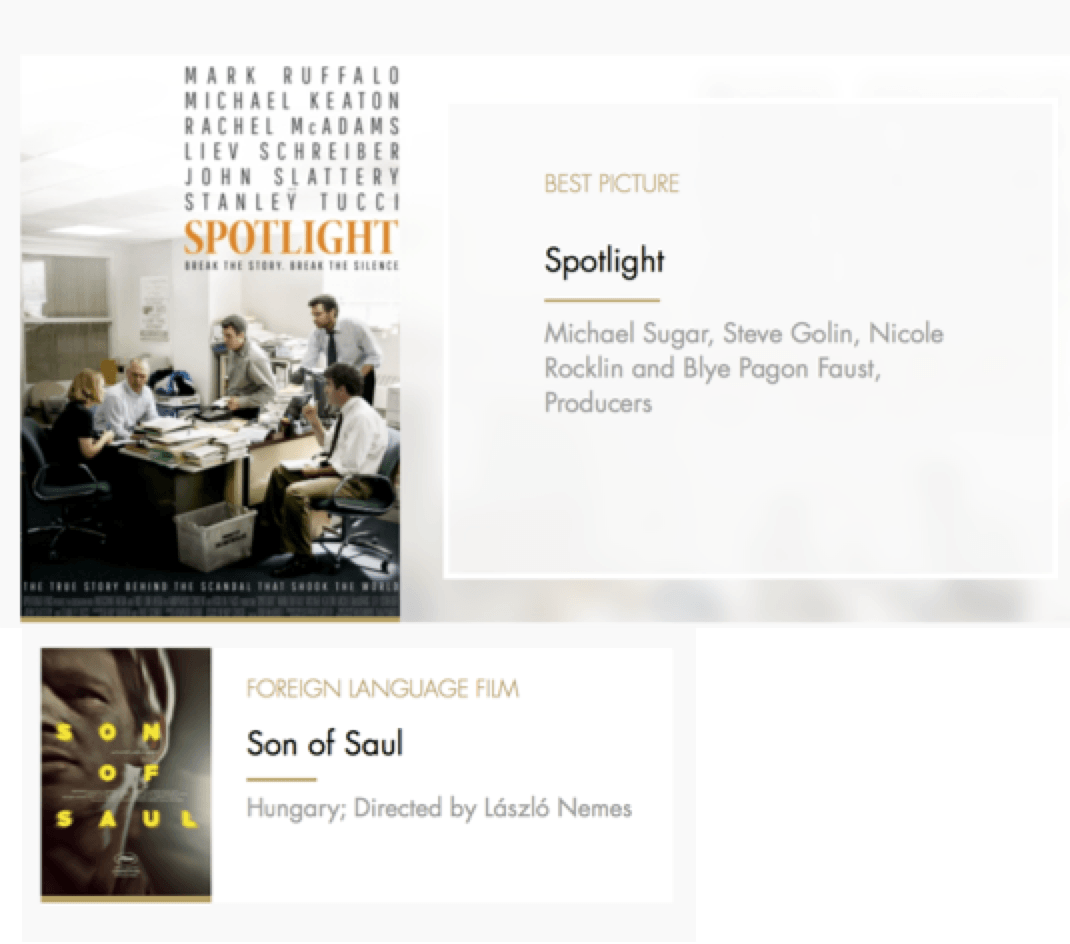

The U.S.’s nationalism is even represented on the Oscars website by presenting the Best Film, Actor/Actress, and Animated Film awards (all American-directed and starred, in addition to being spoken in English with no subtitles) at the top with large photos of each winner, while presenting every other category in small boxes below. In terms of placement, the Best Foreign Language Film award is given the same amount of importance as the Best Sound Editing award.

In the European film festivals, on the other hand, that is not the case. For this year’s Berlin International Film Festival, the first three most prominent awards were given to people of completely different countries. The film festival also makes a point to award movies on categories such as the Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize, a feature film that opens new perspectives. The Golden Bear for Best Film is the most notable award a film can receive, and the Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize is right below that in terms of importance.

From left to right: The Golden Bear for Best Film: Fuocoammare (Italy); Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize: Hele Sa Hiwagang Hapis (Philippines/Singapore); Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize: Smrt u Sarajevu/Mort a Sarajevo (France/Bosnia and Herzegovina)

This festival makes a conscious decision to establish the importance of exposing oneself to new perspectives by specifically rewarding movies that make an obvious effort to do so.

In order to overcome our inherent ethnocentric bias, some embassies consciously make an effort to put on events that combine differing cultures. For example, the Embassies of the Czech Republic and the United States of America created a film festival specifically targeting the exchanging of American and Czech cultures by exposing those from Nicosia and Cyprus to American films but directed by Czech director Milos Forman. It was called the Milos Forman Film Festival and through the combined Embassy efforts, the Czechs were able to be exposed to American culture, while still feeling prideful in their own culture since Forman is from the Czech Republic and, and, subconsciously added Czech cultural references within these American films.

Since movies are such an impactful way to develop a better understanding of a culture different than your own, this type of film festival can be organized in the States as well. French, Japanese, Syrian, Hungarian, etc. embassies in the United States can create film festivals that are directed by people of those descent and represent the cultures of those from those foreign countries as well. There can also be an implementation of film festivals that represent American directors who live abroad and create abroad films in order to create a potential incentive or connection for American audiences to attend these film festivals. One example can be creating a film festival that highlights the work of French director Roman Polanski. Even though he was born in Paris, he has made movies in Poland, Britain, France, and the U.S., marking him the epitome of the quintessential international filmmaker. By hosting a Roman Polanski Film Festival in the states with the Polish, French, and British embassies involved, all four countries can experience and appreciate one another’s cultures, while giving American audiences an incentive to come since Polanski has made popular films in the states as well.

Through this cultural program, American audiences will become more informed about the culture that was represented in the movie he or she saw. And by becoming more informed about a culture, it will allow Americans to not only be less ill-informed, but also more inclined to learn more about said foreign country, it’s politics, international relations, and other foreign countries alike. By acknowledging these different cultures and learning that both your culture and another culture can coexist, it will allow you (American readers specifically) to base future decisions on this knowledge that people, places, and things can be different, and that’s okay.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication.