This is the fourth in a series of posts on life, culture, and politics in the U.S. and E.U. by Robert Entman, who spent 2012 as a Humboldt Research Prize Scholar at Freie Universität in Berlin. Read more posts here.

Naturally Berlin, Madrid and Paris have more history than any US city. It’s not fair to compare them to DC, Philadelphia, New York or Boston, our most history-conscious cities. Still, the reverence for the old expresses itself in public life and policymaking in Europe.

Policy provides more resources for preservation of historical memory while also supporting modern culture. Two examples:

1. Wine

The integration of wine into typically more relaxed and lengthier meals, offers one illustration of Europeans’ ability to live in closer continuity with the past. And like so many other things, the production of wine is heavily regulated, in part because of Europeans’ insistence on honoring that continuity.

Example: In 1395, Duke Philip the Bold issued regulations governing wine quality in Burgundy. It might strike Americans as oppressive, but winemakers in, say, Puligny Montrachet with rare exceptions must specialize in the chardonnay grape, and must follow many detailed government mandates on how the grapes must be handled to be certified as genuine Puligny. The French know that this grape reaches its apogee in the soil and microclimates of the Burgundy region, where vineyards go back at least to the fourth century AD. When you drink a bottle of Puligny you know you will get a chardonnay that to some degree reflects its particular terroir now as it did back when knights and dukes ran things.

Small differences in the way the three cities typically present wine in restaurants further express historical and cultural differences. In Berlin and generally in Germany, wine lists are heavy on German wines; this limits choices of reds since white riesling is the grape that makes the best wines in the cold climate there. If you order a glass of wine, it will come with an etched line marking 10 or 12 ml, and waiters pour to that precise line. Never saw a glass with a line in Spain or France.

One historical quirk of Berlin: when you go out to eat you essentially have to pay for bottled water. Nobody drinks tap water. Supposedly Berliners got used to drinking bottled water after WWII when the infrastructure was in ruins and tap water was dangerous. Some might see this as an example of hidebound Europeans sticking with a dumb and expensive tradition for no good reason. Most restaurants have a deal with one or another brand of bottled water; presumably the water sales add significantly to profit margins. Given the generally reasonable cost of the food, that seemed fair to me.

In Paris on the other hand, asking for tap water is typical, and they usually bring it to the table in a decanter or bottle. On restaurant wine lists and in wine stores too, the French focus is on lesser French chateaux and off-year vintages, presumably because these establishments can’t compete with the astronomical costs of the most famous Bordeaux and Burgundy wines, for which prices are set on an international market. These days, for instance, even a young bottle of Chateau Lafite can set you back over $1,000 at the store. Thank globalization. A little bit of historical continuity is lost to all but the wealthiest French folks and tourists.

2. Memorialization

Reminders of the Nazi past are omnipresent in Berlin. As one among many examples, there are small brass stumbling blocks throughout Berlin. Slightly raised from other cobblestones, they are designed to ever-so-slightly trip pedestrians, who then look down and can see the name, dates and fate of a Jew who once lived or had a business at the building where they’re standing.

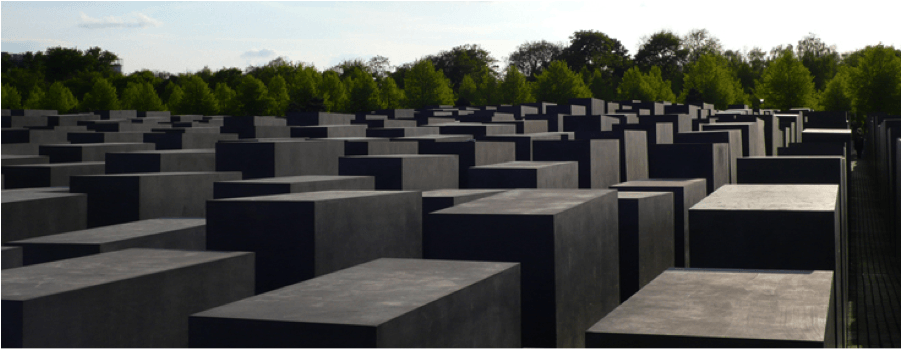

Consider also the striking Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. The Memorial is located in the heart of the new Berlin, bordering the American embassy and the Tiergarten (Berlin’s Central Park), near the Brandenburg Gate. So Berliners will frequently see it, register it if only unconsciously and thus potentially think about its meaning. The location and design of the Memorial engendered decades of public debate and controversy, a process that itself exemplified healthy democracy. Although much smaller than the Holocaust museums in DC and Jerusalem, I found the museum that’s integrated into the Memorial as thought-provoking and powerful.

Compare what the Germans have done to ensure accurate and persistent memories of their past misdeeds with US actions to commemorate and keep alive memories of the US’s own holocausts involving Native Americans and African Americans, not to Vietnam and Indochina. As far as I know, there is no public reminder in DC that might cause a typical citizen to reflect on how the American government’s policies and, arguably, war crimes in Vietnam caused untold and indefensible suffering there, not just among Americans. Our Vietnam War memorial is a great and justly popular tourist site, but it focuses memories only on our losses.

Yet, policies that make history a daily presence for citizens—including the bad or horrific history, not just the glories like France’s wine—might just make for a better future.