U.S. Pro-Democracy Narratives on Bolivian Coup are Heavily Contested Due to Their Anti-Democratic Results

By Ben Gutman, MA Global Communication ’22

Throughout the Cold War, U.S. presidential administrations and other federal departments weaponized the idea of anti-communism to dominate media frames and discourage dissent. U.S. government officials have successfully employed a “spread of democracy” frame to justify proxy wars, covert intervention, and regime change against leftist Latin American governments with developing democratic processes. This frame has facilitated the projection of the U.S. master narratives of American exceptionalism and free-market capitalist individualism onto other sovereign nations.

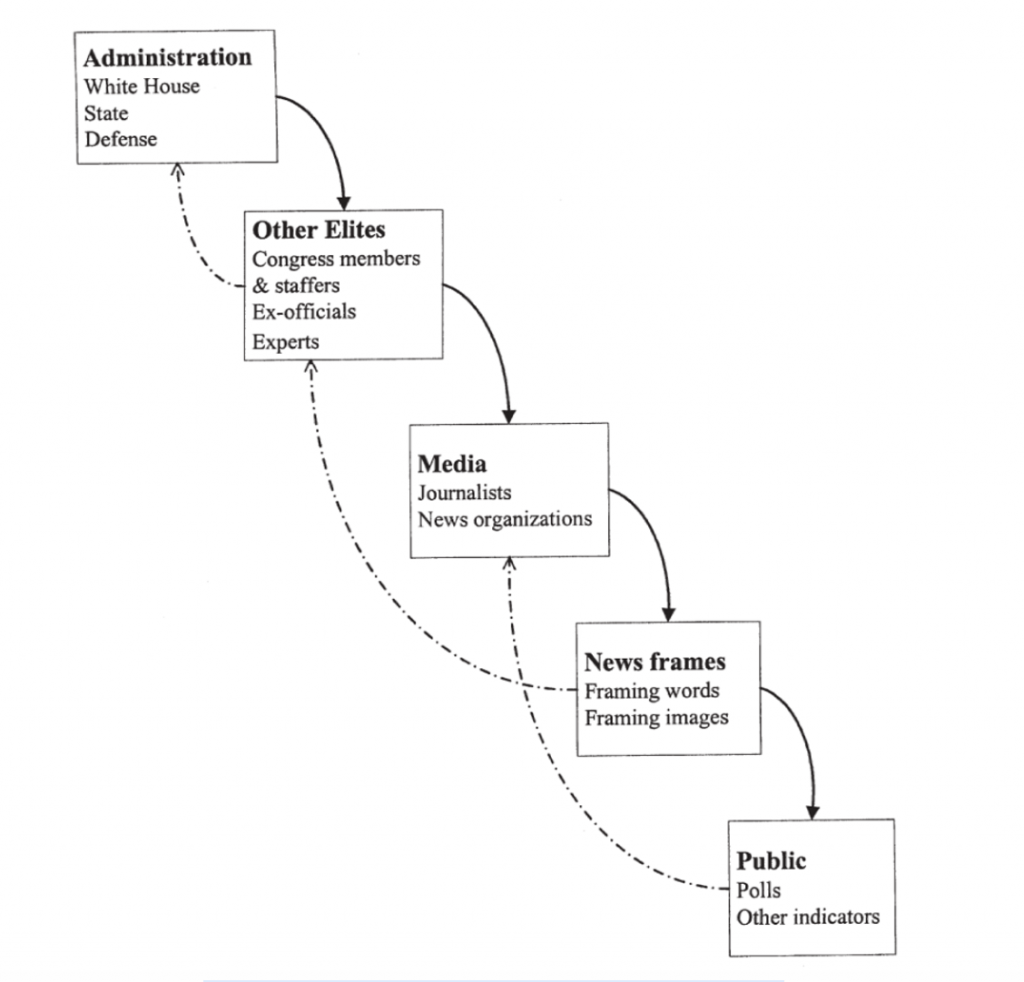

One useful way of understanding narrative contests is Entman’s Cascading Activation Model, which describes how government frames are pushed down to other elites, news organizations, and the public. Entman uses the real-world cascading waterfall metaphor to highlight the hierarchical stratification of the cascade, which makes it easier to spread frames down the cascade rather than up.

Following the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and an increase in U.S. interventionism in the Middle East, the U.S. paid less attention to Latin America. This allowed many Latin American countries like Bolivia to develop their democratic political systems. The strengthening of Bolivian representative democracy was highlighted by President Evo Morales’ creation of the Plurinational state in 2009, which guaranteed political representation to all indigenous Bolivians. A relatively healthy democratic process in a socialist state with control of valuable natural resources like Bolivia, presented multiple narrative contestation problems throughout the U.S. government’s quest for regime change, despite access to elite institutions used to spread its frame of choice: election fraud.

Narrative used to justify U.S-backed coup in Bolivia met with undeniable contestation

First, the U.S. state narrative found pervasive contestation through informational content produced by academics, progressive journalists, and non-profit organizations within the Western and Bolivian media ecology. On Oct 20, 2019, the U.S. proxy Organization of American States (OAS) issued a report alleging “intentional manipulations” and “serious irregularities” in the Bolivian presidential election of Evo Morales.

These claims were immediately debunked and repeatedly proven to be a false narrative designed to endorse an anti-democratic seizure of power. The election fraud narrative was in congruence with mainstream media motivation and uncritically re-published by the New York Times. On Nov 10, 2019, Jeanine Áñez’ white supremacist, Christian neo-fascist dictatorship took power in a military junta.

Second, despite U.S. domination over Western media infrastructure, viral social media content of violent government oppression contested the pro-democracy U.S. narrative. Throughout eleven months of economic mismanagement, extreme corruption, and brutal repression against indigenous protesters resulting in dozens of extrajudicial murders, the U.S. state narrative grew less and less compelling. However, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo continued to voice strong support for the military coup and the “return of democracy”, the OAS continued to deny its involvement, and Western mainstream media continued to whitewash the Áñez regime’s crimes.

While the messaging campaign was successful in its short-term regime change goals, it was unsuccessful in its impact on Bolivian public opinion and international solidarity with the Bolivian people. Mass public uprisings and grassroots worker movements forced new elections and on Oct 18, 2020 another socialist, Luis Arce, was elected.

Continued pro-coup regime narrative hampers Bolivian drive towards justice

Despite frame contestation from influential voices in the Western media ecology and emotional-triggering online content displaying the coup regime’s savagery, the vast majority of mainstream publications continued to reinforce a damaged and hypocritical pro-democracy U.S. narrative. On March 13, 2021, Bolivian authorities arrested Áñez and charged the coup leader with terrorism and sedition, the same charges previously levied by Áñez against former president Morales. Two days later, the OAS released a statement expressing concern “about the abuse of judicial mechanisms” as a “repressive instrument of the ruling party”.

This narrative of “rule-breaking” and “revenge”, revolving around the Áñez arrest, functioned as another anti-democratic assault against an elected socialist government and its ability to exercise sovereign control over its rule of law. On March 18 the Washington Post Editorial Board wrote that “Mr. Arce appears to have reverted to a more one-sided and vengeful leadership style characteristic of Mr. Morales” and referred to Áñez as the “conservative then-interim president”.

A March 15 CNN analysis mentions the invalidation of the 2019 election results, but fails to include any reference to the invalidation of the report used to invalidate the election results. The article continues with a section titled “vague charges” that characterizes the charges against Áñez as “broad” with “proof scant”. However, an Áñez decree that gave immunity to all deployed military personnel culminated in the massacre of more than thirty protesters, in addition to a plethora of other human rights abuses.

The blatant dishonesty and bad faith framing from mainstream media sources on Bolivia is rooted in the U.S. government and OAS’s persistent use of the same pro-democracy narratives that yield anti-democratic results. The OAS has never admitted to its role in the 2019 coup, has never apologized to the Bolivian people, and has even continued to spread misinformation on the Bolivian political process. Unfortunately, Biden’s State Department under Secretary of State Antony Blinken has continued to weaponize the U.S. master narratives of “democracy” and “human rights” to persecute a perceived hostile government for its role in attempting to deliver justice for the victims of the coup’s violent crackdown.

Recommendation

The Biden administration’s State Department should stop reinforcing a heavily contested framing of the Áñez arrest as a human rights and due process issue. This frame has cascaded to mainstream media, which continued an unconvincing pro-coup regime narrative. This narrative violates the Arce government’s sovereign democratic right to prosecute Áñez in accordance with Bolivian law and helps deny Áñez’ victims justice, but also adds to an increasing resentment from Latin Americans towards “pro-democracy” US interventionism.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

13 thoughts on “U.S. Pro-Democracy Narratives on Bolivian Coup are Heavily Contested Due to Their Anti-Democratic Results”

Very well-written and informative. I knew US involvement was heinous and influential in Bolivia, but I had no idea how insidious and far-stretching it was

Was Evo Morales justified in attempting to change the constitution while he was still in power though?

It’s disappointing that after reading my piece your first reaction was…what about Morales? However, I’m not surprised and expected this question to be asked. Unfortunately, this question is the very result of the “spread of democracy” frame that cascades down to the public in the United States. Whenever the U.S. government is interested in regime change, they demonize and exploit the very new “developing democratic processes” that I mention and frame the leader as an “authoritarian dictator” without deeper analysis of local politics.

Morales is by far the most popular political figure in Bolivia, a country whose population is majority indigenous from humble backgrounds. Morales himself is the first indigenous president of Bolivia and grew up a cocalero, later becoming a leader in a worker’s union. In fact, Morales was an active union organizer during the 2003 Gas War in El Alto when then president Carlos Mesa (the capitalist, neoliberal candidate who he ran against and defeated by a wide margin in 2019) was exploiting Bolivia’s large natural gas reserves and selling them off to private corporations. So, it’s no surprise that a presidential candidate who stands with the vast majority of Bolivians against capitalist exploitation would be able to defeat the very man who sold Bolivian natural resources to the highest bidder.

Morales was first elected in 2006, but creates the new constitution in 2009 which gives presidents the possibility of two 5 year terms in office for a total of 10 years. This constitution also greatly improved Bolivian representative democracy, which I also mention in the article. I would argue that Bolivia has a more representative democracy than the United States (I had the misfortune of being born, raised, and a life-long resident of D.C. where I am not represented in Congress despite being a taxpaying American). However, because the constitution was established in 2009 that meant that Morales’ constitutionally allotted time was set to expire in January 2020 (this is important and I will come back to it) after his mid-term election. The establishment of a new constitution as being good for democracy is something that’s unfamiliar to Americans, since we use the same constitution that was created when human beings owned other human beings.

In 2016, Morales’ MAS party initiation of a national referendum to expand presidential term limits failed. A few years later the MAS initiated the same expansion of presidential terms, but through the judiciary, which eventually passed. Was this a MAS effort to remain in power past the constitutionally allotted time? Yes. Did the OAS allegations of election fraud have anything to do with this? No. I lived in Bolivia during the summer of 2016 and met plenty of people who were not happy with Morales. In fact, his approval rating had slipped since he was first elected and some indigenous communities were concerned about the extraction of natural resources from indigenous lands (although Morales’ nationalization of natural resources allowed for vast majority of profits to reach the people in the form of social programs).

Before I talk about the coup it’s important to know that Morales had actually agreed with the OAS to re-do the 2019 elections before the coup because he understood the potential for U.S.-led regime change. However, the far-right extremist Bolivian political faction, which receives support from the U.S., refused the terms of a new election. The coup occurs in Nov. 2019, 2 months before Morales’ constitutionally mandated term is set to expire. And as I explain in this piece, the OAS makes the false claims of election fraud paving the way for a violent coup regime to take power in a very anti-democratic way. You’d think that U.S. officials would be more sensitive to countries that have undergone a coup (let alone a U.S.-backed coup) after the events of January 6th, but alas sensitivity is not a priority in US foreign policy.

So…if you think the U.S. is justified in its regime change goals and support for the coup because of a Morales judicially-passed amendment to the constitution, then you’re entitled to your opinion. But if this minor detail justifies regime change, that just unleashes a whole other level of U.S. hypocrisy in its support of Saudi Arabia, Israel, Colombia (whose government is currently massacring human rights activists) etc.

Ben, this was a fantastic read, albeit a disturbing one. The way we think of coups is usually through covert influence and back-office politics, but the fact that these narratives and frames are being disseminated so openly and blatantly – and being able to get away with it for the most part – is shocking. The contestations are available if you merely scratch the surface – but perhaps that is what the problem is. Mainstream media and narratives are pervasive and easy to consume, and it is through the careful omissions and insinuations that opinions get formed and information is not questioned.

I have two questions: Given that it doesn’t seem the U.S. is going to stop using these narratives anytime soon, how do you think we can bolster or augment the counter-narratives or make them more visible? And, as many people might know, Elon Musk was quite the viral “subject matter expert” on the coup – how does his involvement fit in the U.S. government narratives and cascade?

Great work, Ben. I can tell that a lot of research and thought went into explaining this complex issue. My focus immediately went to messaging campaigns, specifically short-term versus long-term. I feel like short-term campaigns run the risk of achieving a quick goal, but not considering the overall public opinion of a population. If the U.S. employs a longer-term messaging campaign, it should stay away from specificity around things like regime change that could change with the times, and appeal more to the people who will take this message far into the future, like young Bolivians.

Saiansha—two great questions and the first has no easy answer. I agree that the U.S. is not going to stop using these hypocritical narratives anytime soon, so it’s necessary to see them for what they really are and bolster counter-narratives. This is difficult in the current media ecology in which U.S./Western mainstream media (MSM) effectively function as “stenographers for power” (as journalist and liberation theologist Chris Hedges calls them) when it comes to U.S. foreign policy objectives. Journalists who shine light onto counter-narratives like Chris Hedges are fired and treated like a pariah. MSM also buries a small number of articles that highlight counter-narratives amongst far more that align with the state narrative. For example, I use two Washington Post articles as sources in my piece. One is an article by research scientists at MIT’s Election Data and Science Lab that exposes the OAS false narrative. However, the other is by the editorial board that supports the OAS false narrative. So WashPo will throw you a counter-narrative bone every once in a while. But it’s always good to be critical, analyze these articles in terms of strategic narratives, and most importantly read and share alternative media sources/watchdog journalism (I cite numerous including Mint Press, FAIR, and Common Dreams).

It’s also important to see the macro picture from a different lens. For example, the current master narrative of neoliberalism is very good at manufacturing consent through the use of specific terminology and characterizations of the world. Historian and author Vijay Prashad does an excellent job of analyzing liberal narratives and countering them with an anti-imperialist narrative. For example, liberal media often characterizes a U.S.-backed coup or invasion of another country as a “mistake”, insinuating that it was just a mishap in an otherwise benevolent U.S. trajectory. However, if you look at the international landscape as imperialism vs. De-colonization, you begin to see that Western colonization and imperialist aggression is still very much alive and well (bombings, sanctions, regime change, debt peonage etc.). Utilizing different master narratives to characterize the international arena functions as a great counter-narrative.

Your second question is much easier to address in my opinion. American political theorist Sheldon Wolin coined the term inverted totalitarianism to characterize the U.S. political system. This describes a system where corporations have subverted democracy through big monied interest groups, lobbying, campaign finance, corruption etc. If we’re being honest you could add another piece to the cascade model above administration (White House, State, Defense) and call it corporate oligarchy. These corporations have incredible influence on politics and absolutely have a role in pushing frames down the cascade. Musk is one of the wealthiest men in the world. Tesla depends on Lithium to power its electric cars. Bolivia has the largest Lithium deposits in the world. It’s not hard to connect the dots there. In fact, the Bolivian coup very closely resembles the 1954 CIA orchestrated coup against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala. Arbenz was a big advocate for land reform and redistribution, which was a direct threat to the United Fruit Company. The U.S. orchestrated the coup not to promote democracy, but to save corporate America from losing money.

It’s actually quite fitting that corporate interests looked to privatize Bolivian natural resources to increase their wealth seeing as this has been the case since colonial times. The Bolivian gold mines of Potosi yielded the most gold for colonial nations in the Americas. This trend of exploitation and intervention has been going on for a long, long time.

I appreciated the presentation of Entman’s Cascading Activation model early on, and hoped to see more of the argumentation relate back to how the dynamics in Bolivia reflected the processes Entman describes. Your own framing of the Morales government’s narrative was detailed and presents a side less covered in U.S. press, and added value for that reason. It’s hard to assess some of the normative aspects in the argument (OAS as a US proxy, Anez as neo-fascist/white supremacist, describing 2019 as a coup, and finding of false narrative or unconvincing narrative) without more of an empirical presentation, so in my view that weakens the argument you make. How did the two sides present their narratives within Bolivia – and what role did newspapers, websites, protest networks etc play in dissemination? All in all, an enjoyable read.

Excellent analysis of a disturbing yet important issue. I appreciate the thoroughness with which you covered the coup from the previous Bolivian regime to the Biden Administration. I thought your blog showcased some of the positive impacts of social media as it relates to the cascade model, as Bolivians were able to share content that illuminated the extent of governmental oppression.

I couldn’t help but find some similarities between Bolivia’s negative sentiment towards the U.S. after this coup, and the anti-U.S. sentiment that was fostered in the Middle East leading up to 9/11 due to U.S.-led coups and regime changes. Even decades after the attacks, managing relationships in that region and fostering trust proves to be difficult. So, like Maddy, I was also drawn to the idea of short-term versus long-term approaches to foreign policy. This example raises questions of whether the U.S. is truly committed to building long-term relationships, or if short-term solutions, regardless of their impact on these relationships, will always win out.

This was a fascinating read; the explanation of events was quite thorough. Clearly the U.S. needs to have a better understanding/more awareness of how its history in Latin America is viewed by people there and how this affects its relations in Latin America. Like Nikki said it was quite interesting to see how the Bolivian people have used social media to subvert Entman’s Cascading Activation Model. The U.S. narrative is not taking hold, but even for narratives more rooted in truth, how does one know when to give up on or change their narrative?

I still remember the difficult conversations in social media related to the coup. I have to say this was an excellent analysis using the Cascading Activation Model. By using the model, the blog truly helps to explain such a contentious issue in a way that it makes it easier to see how the United States has played its part in destabilizing Bolivia, and other Latin American countries. While I do agree that the United States should stop reinforcing the current narrative, I would like to know how you would reframe the USA discourse, using the current narratives (master and identity narratives) it possesses.

Ben, this was a great analysis of the role of the Cascading Activation Model in a very recent issue. This piece really helped to paint a strong picture of how the US narrative has worked against the people of Bolivia on the world stage. You mention the mainstream media ignoring proven facts and the continuation of the narrative from the Trump administration into the Biden administration. Why do you think that both administrations have taken the same narrative on this issue? and what do you think would be a good way for the Biden admin to pivot their narrative?

Excellent analysis Ben. One would think that “the spread of democracy” frame is dead but this example proved that it is alive and still used to justify US intervention in foreign countries. The other important takeaway I get from this article is that Entman’s cascading activation model in some cases still works perfectly, the fact that US mainstream media bought the US administration frame without contesting it is very telling. I wholeheartedly agree with your recommendation.

Great information, research, and analysis!