We’re living through some really tough times right now, especially for our Black friends and classmates. The UHP will be issuing an official statement on all this soon, but in the meantime, Professor Aviv has some fascinating thoughts on how the hellish realities of racism are not necessarily permanent but constructed.

It is a beautiful day outside, a Sunday morning. I sit at my desk with the lovely scene of trees in the yard. This is the bliss of summer break. Working at my office, it is not too hot just yet, and the birds are creating a sweet harmony that no Spotify playlist can best. But this quiet is deceiving, and this summer break is far from ordinary. These are days of disorientation and pain. The coronavirus pandemic exposed deeply rooted social fault lines. The economic toll is unimaginable and the mental pain of loneliness and being apart from our communities, friends, and systems of support makes the crisis much worse.

As if the health crisis was not enough, the horrors of this pandemic joined forces with much older ones, those of racism. Together they have created a tsunami of incredible pain, rage and violence. These visions haunt me; a policeman who kneels on the neck of George Floyd, the vigilantes who murder Ahmaud Arbery, followed by an outburst of rage and violent police backlash. Protesters in the streets are exposed to the threat of human violence and the havoc of COVID-19, many of them live in communities already vulnerable to the virus. Emotions of sadness, anger and helplessness flood me and fill me with an almost desperate need to make

sense of this chaos.

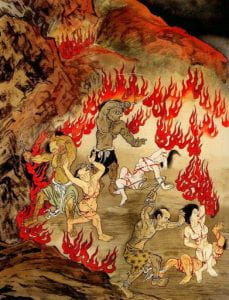

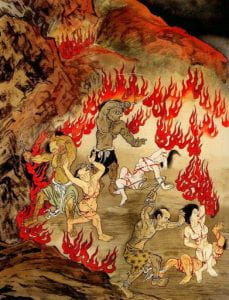

One powerful image that comes to my mind is that of a Buddhist hell. According to ancient Buddhist texts, our world includes six realms of existence. In the middle is the messy world of humans, filled with desires, anger and confusion but also with compassion and the possibility of change. There is also a realm that is a blissful world of divine beings who are fortunate to be free of most things that torment us, and then there are the Buddhist hells. A Buddhist hell is a place where no one wants to be.

Hells in the Buddhist imagination includes creative ways for its inhabitants to exist miserably. There are many hells, but they share some important characteristics. Denizens are often suffering from systematic abuse, life is a lengthy experience of fear and pain, and there are hell guardians whose job it is to keep the structure and institution of hell running. The environment is contributing to ones’ suffering, either too cold or often too hot, suffocatingly hot. Unlike in the mon otheistic version of hell, there is a way to leave the Buddhist ones, but it takes a long time and extraordinary effort.

otheistic version of hell, there is a way to leave the Buddhist ones, but it takes a long time and extraordinary effort.

But where are those hells? Are they real?

According to one school of Buddhist thought, the Yogācāra or Mind-Only school, these are the wrong questions to ask. All worlds are created by our minds, and hell exists for beings whose shared experiences construct their world as one. But if we, too, construct our world, in recent years our shared creation looks more and more like a Buddhist hell. Think about the policeman (or policemen) who kneels on George Floyd’s neck. They are as human as you and I; they are people who were shaped by our social realities to become violent police officers. They bear responsibility, and so do we. This is not to assert an accusation, but as a statement about the deep, interconnected causal nexus that we are a part of. We are shaped by this world and shape it. These policemen grew up into this world where a black person is immediately seen as a suspect. It does not matter if that person is jogging around the neighborhood (Ahmaud Arbery), enjoying birds in the park (Christian Cooper), or just sitting at home (Botham Jean). Black Americans live in fear that they do not deserve. But it is not only black Americans, Asian Americans are also a target; Jewish Americans see a rise of antisemitic attacks; Americans originally from Latin America are abused by our immigration system. As evident from the rise of white supremacy, many white Americans are fearful too. They fear for their livelihood, fear of the pandemic, and the opioid addiction that has devastated many small cities. When we

construct a Buddhist hell, no one can be free from the suffering it entails. Some could have the illusion of safety, but as the COVID-19 taught us, when our social infrastructure is failing, a virus does not care to distinguish between which bodies it inhabits.

When pain consumes enraged fellow citizens, the streets of all of us are burning, the glasses around all of us are shattering. But here is the silver lining: this is a reality that we have constructed, and one that we can dismantle. When I say that “we have constructed” this reality, I do not mean just you and me; I mean you and me as well as generations upon generations of those who come before us. This is why the structures of this reality are so hard to dismantle. As my students and I recently discussed in my Buddhism and Cognitive Science course, we have sound evidence to show that these sorts of habituations form our individual

and social identities. They are the “eyes” through which we “see” the world. Except that we do not really see ‘it’–rather, we are constructing our world again and again. Together, we can recreate the same patterns that make the world more like a Buddhist hell, or we can create a better human realm with all its imperfections.

I am not deluding myself into the belief that we can entirely dismantle racism, sexism and other forms of social ills including cruelty to non-human animals. Nonetheless, we must act. In a recent interview that went viral, Cornel West cited Samuel Beckett in a way that captures this sentiment very well: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” We have to try. Our efforts will fall short, because as Buddhist cosmology tell us, the human realm is ever messy: we are not divine beings. But we need at the least to fail better. In one of the most profound Buddhist texts, A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, Śāntideva, an 8th century Buddhist monk and philosopher, instructed his readers about the perfection of the virtue of generosity. He reminds us that if it was possible to solve social ills like poverty, the Buddha and other sages who were smarter than us would have figured it out before. These are hard problems, but he reminds us of this not to discourage us, but to encourage us to commit

to action even when the results are unguaranteed: Śāntideva said that “the perfection of generosity is said to result from [a] mental attitude” (Crosby and Skilton 1995, 34). Our intention matters. To dismantles the structure of racism, sexism etc. we need a commitment, a sacred vow. This is because there will always be viruses, just as we will always have racists and sexists within our communities. It is not about the outcome: it is about the commitment to constructing a better human realm. We owe it to George Floyd, to Ahmaud Arbery, to Breonna Taylor and the countless victims of the pandemics that could still be alive today. We owe it to ourselves.