I didn’t realize how distinctly American I was until I began my study abroad experience in China. I knew I was an outsider when I was walking through YuYuan Garden and was met with deadlock stares. I was aware that going crazy in arcades garnered the stares of people who did not realize that the avid arcade culture is something that is unique to China. However, this became especially apparent when I began my classes at Fudan University. There is something unique about the way that American students perceive their presence within a classroom that can be categorized under the characteristics that seems to define all Americans abroad: loud and obnoxious.

YuYuan garden during the day (left), when entry costs around five dollars a person. The same garden area during the annual lantern festival, this year in celebration of the Year of the Pig. Pig decor and memorabilia are especially common in Shanghai this year!

On my first day of class my friends and I arrived at Fudan University fifty minutes before class began, purely driven by first day nerves. What could barely be defined as a crowd of American students, three or four at best, had now become the sole source of noise in the hallway outside the classroom. We complained about the commute, passionately expressed our interest in acquiring breakfast, and constantly messed with the touch screen tablet that is stationed outside every classroom. Putting it not so delicately, we were being loud and obnoxious. Enter another foreign exchange student, headphones in, eyes averted to the ground, clearly not in the mood to talk. Naturally, we asked her what her name was and where she was from. When she responded that she was from the Netherlands and returned the question, four scattered and equally jarring voices responded “America!” She then did what most people do when they see a crowd of loud and obnoxious foreigners: she smirked, nodded mockingly, and said, “yeah I figured.”

Fudan University in Shanghai. This is one of Fudan’s two campuses, were most of my classes take place. Students enjoy many locations to relax within the traditional campus setting.

That was an interesting experience for me, to say the least. I had never identified myself as an American. According to my passport, I am not. However, there is a level solidarity that I now feel with my classmates. Regardless of our own cultural backgrounds, we had all been somehow influenced by our time in America; it effected our behavior, our mindsets, and the way we viewed our responsibilities as students. American students are more rambunctious, both in their behavior and their academic ideas.

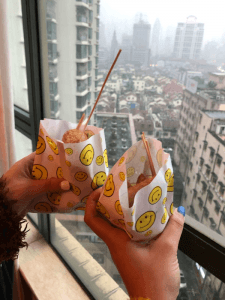

(From left to right) A Chinese vintage store in Tianzifang, Shanghai. One of the many gigantic arcades located around the city, this one was also in Tianzifang. “Fried Ice-Cream” from a small fried foods stall across the street from our apartments. These turned out to be fried deep purple balls of custard and not ice-cream at all. They were still absolutely delicious!

This became clear to me in my business class. When asked to pitch a technological innovation that would improve student life, there was a clear division of groups: Americans and other foreign exchange students. The American students went wild, we pitched a cafeteria app that would eliminate language barriers, account for dietary restrictions, and even tell students how busy the cafeteria was before they got there. Ambitious, as expected, but also, as our teacher explained to us, very difficult to implement and coordinate. The other group came up with a feasible library cataloguing database for which the technology was readily available. The teacher loved it.

This made me question whether or not this blind ambition was beneficial to us as students. Perhaps it would be better to stick to safer options. I have come to the conclusion that neither option is superior, they are just starkly different. They are reflections of the diversity of human thought, traditions, and culture. My academic experience has been opening me up to facets of educational practice, student culture, and social etiquette that differ drastically from what I am used to. I am very excited to dive into this new type of student life and gain different perspectives on what I had previously understood as the accepted order of things.

Two incredible views of Shanghai. The first is from my apartment (left) and the second if from the YuYuan Garden metro stop (left) which is the starting point of our forty-five minute commute to Fudan University.