Leah Steckler, MD

January 15th, 2018

As we enter the New Year, it is hard to forget the many lessons of 2017, a year that will likely be remembered for several reasons, among them the seemingly never-ending natural disasters. This past September, Hurricane Maria was the most powerful to hit Puerto Rico in almost 100 years (1).

Hearing stories from providers, like that from Dr. Zorrilla’s account published in November in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) gives us a glimpse into what it might be like to practice in a far less than ideal environment (1). Importantly, Dr. Zorilla, an obstetrician-gynecologist, notes that neither she nor her staff had training in disaster management, and that it would have been difficult to predict and prepare for the level of devastation that Puerto Rico experienced. When a hospital is involved in a natural disaster, it is still vital to provide good quality patient care with few interruptions despite limited resources.

Accessing clean water was one of the challenges described in the NEJM article. According to the World Health Organization, 15% of patients worldwide develop an infection during a hospital stay, and this occurs with increased frequency in low-income countries with limited access to clean water (2).

Keeping track of any acquired illnesses, and accounting for chronic problems, also proves to be difficult without access to electronic medical records. Having a good contingency plan, formulating a strong back-up system, preparing for other simultaneous technologic emergencies, and planning for post-outage processing, makes a difference (3). Training staff ahead of time to know how to use a paper system may also be prudent. These concerns also extend to research. Having back ups for data and specimens can prevent mother nature from destroying valuable contributions to the scientific community, as happened to many in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (4).

Without clean water or reliable electricity, treating patients in need of emergency surgery required urgent transport to the United States (1). Maintaining an adequate supply of sterile surgical equipment for those who stayed on the island also proved challenging because Dr. Zorilla’s team was unable to autoclave instruments.

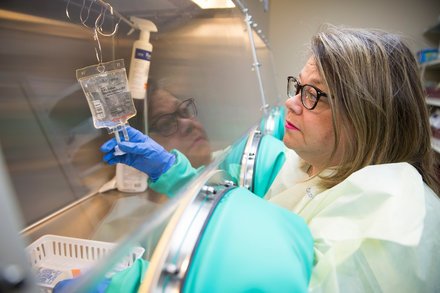

An unexpected consequence of Hurricane Maria was its effect on drug manufacturers. Baxter pharmaceuticals and Johnson and Johnson both have factories in Puerto Rico and provide numerous medications and additives to the United States (5). This has forced hospital administrations and providers to find alternative medications and new suppliers.

Puerto Rico certainly experienced devastation beyond what most can imagine. The lessons gained from last year’s numerous natural disasters have challenged practitioners to be better clinicians, improve emergency preparedness, maximize ingenuity, and use teamwork to overcome innumerable obstacles.

What will you do to protect your hospital and emergency department when the next natural disaster strikes?

Resources:

- Zorilla, CD. The View from Puerto Rico — Hurricane Maria and Its Aftermath. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 9;377(19):1801-1803.

- Drinking Water. World Health Organization. July 2017. Available online at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs391/en/

- Minghella, Linda. Be Prepared: Lessons from an Extended Outage of a Hospital’s EHR System. 2013. Available online 3 Jan 2018 at: https://www.healthcare-informatics.com/article/be-prepared-lessons-extended-outage-hospital-s-ehr-system?page=2

- Singer, E. Research losses surface in hurricane Katrina's aftermath. Nat Med. 2005 Oct;11(10):1015.

- Thomas, K. U.S. Hospitals Wrestle With Shortages of Drug Supplies Made in Puerto Rico. Available online 23 October 2017: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/23/health/puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-drug-shortage.htm

Leah Steckler, MD is an Emergency Medicine Resident at The George Washington University Hospital