The management of cardiac arrest is standardized and based on consensus guidelines for all provider levels [1]. In the United States, the most commonly accepted guidelines are those of the American Heart Association. Despite efforts to disseminate these guidelines and educate the public on emergency cardiovascular care, the national rate of survival to hospital discharge for EMS-treated atraumatic cardiac arrest is only 11% [2]. There is significant room for improvement, therefore, it is important to consider innovations in this area.

I sat on the QA/QI committee for my collegiate EMS agency from 2013-2015 and had the opportunity to work with a medical director that encouraged provider involvement in quality improvement [3]. In 2014, we developed and implemented a Clinical Operating Guideline for the use of Impedance Threshold Devices (ITDs), a Class IIa (Benefit >> Risk) recommendation per the 2010 AHA guidelines. In 2015, the AHA updated their guidelines and changed the use of ITDs from a Class IIa (Benefit >> Risk) to Class III (Benefit = Risk) recommendation. By 2017, ITDs were phased out of service. What changed?

Impedance Threshold Devices

The main purpose of CPR is to restore flow of oxygenated blood to the brain and heart. There are two key theories that offer a basis for how this may occur during chest compressions [4]. The “cardiac pump” theory postulates that blood flows because the heart is squeezed between the sternum and the spine. The “thoracic pump” theory postulates that compression of the chest wall causes intrathoracic pressure to exceed extrathoracic vascular pressure and subsequent ejection of blood from the heart into systemic circulation and expiration of air from the lungs. However, the thoracic cavity pressure gradient is attenuated by passive inspiration of air with decompression (i.e., chest recoil) in cardiac arrest.

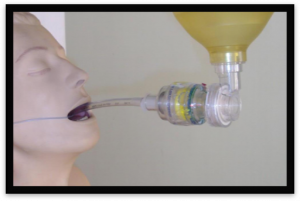

The ITD is designed to limit this.

Figure 1: Mapping Intrathoracic Pressure [5]

The ITD is a disposable one-way valve that attaches to an airway circuit and regulates intrathoracic pressures to maintain negative intrathoracic pressure during chest compressions by preventing air from entering the lungs between chest compressions, enhancing negative intrathoracic pressure. Often times ITDs will come with a flashing light to concurrently guide ventilation rate.

What Changed?

According to the AHA’s Summary of Key Issues and Major Changes, the ITD’s drop from Class IIa to III recommendation was driven by a single large multicenter randomized clinical trial known as the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) Prehospital Resuscitation using an Impedance Valve and Early vs. Delayed Analysis (PRIMED) trial [6]. The ROC PRIMED included ten sites across the United States and Canada (n = 8,718), and failed to demonstrate any improvement associated with the use of an ITD (compared with a sham device) as an adjunct to conventional CPR. After two years of preliminary data suggesting equivalence of risk and benefit, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stopped enrollment in the trial [7]. The often erroneously interpreted conclusions of this trial echo throughout the annals of ancillary devices for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and, without much thought, agencies have systematically been taking them off their units. While the ROC PRIMED trial is an excellent resource for driving future academic work, the findings are not actionable and should not inform prehospital practice.

Anyone who has followed CPR research over the years knows that enormous resources are allocated to perform these trials and there are often more questions about study design than conclusions about the interventions being tested [8]. Olasveengen et al. titles this the “why-all-cardiac-arrest-trials-are-neutral”-puzzle, and highlights a few reasons why [9]. The presence of subgroups within a study with significant differences masks any potential positive and/or negative effects within an entire study population. In the ROC PRIMED trial, baseline neurologically intact survival rates ranged from 1.1% in Alabama to 8.1% in Seattle [10]. Is it fair to assume that an ITD will have equal effect in both Alabama and Seattle? Among the ten different sites, there was also variation in BLS CPR protocols being used (i.e., CPR with face mask, 30:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio). Additionally, data collection spanned benchmark outcomes such as ROSC on arrival at ED, survival to hospital admission, and survival to discharge. Researchers did not control for how closely tied these outcomes are to the quality of post-resuscitation care. More than half of included patients received substandard CPR. In a post hoc analysis of their previously published work, researchers stratified patients with high quality CPR and lower the risk of a poor outcome and found a statistically significant benefit from the ITD [11]. With variability in CPR quality, there was no surprise to find variable effect of the ITD.

Conclusion

The quality of CPR delivered to a patient in cardiac arrest can be a significant effect modifier in clinical trials. Future work in this area should be guided by the notion that the multi-faceted nature of cardiac arrest management is prone to heterogeneity and should be controlled for when designing studies. Additionally, interventions are not mutually exclusive. Research should be refocused on building a systems-based approach to care that considers a combination of therapies.

“Why do we continue to look for a single silver bullet to treat cardiac arrest when we know that every complex disease conquered by modern medicine was done so with a multipronged approach? Isn’t it time to admit that no single intervention […] will significantly improve survival from cardiac arrest, and only a combination of therapies, implemented in a systems-based approach, is the answer?” - Dr. Keith Wesley, Minnesota’s EMS medical director [12]

Future Directions

In Resuscitation, Moore et al. (2017) compared brain blood flow between the Head Up (HUP) and Supine (SUP) body positions during a prolonged CPR effort of 15 min, using ACD CPR and ITD in a porcine model of cardiac arrest and found brain blood flow to be 2-fold higher in the HUP position. These positive findings provide strong pre-clinical support to proceed with a clinical evaluation of ACD CPR + ITD in humans in cardiac arrest [13].

In The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Niforopoulou et al. (2017) assessed whether the use of an ITD during CPR reduces the degree of post cardiac arrest Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) in a porcine model and found that ITD during Active Compression Decompression (ACD) CPR increased 48-hour survival and decreased the degree of post-cardiac arrest AKI in the resuscitated animal [14].

Ameer Khalek is a MPH student at the GWU Milken Institute School of Public Health