By Maria LeLourec

After Dean Randall Abate shared the inspiring climate justice story of Saul Luciano Lliuya, who is Peruvian like us, we became enchanted and did not hesitate to answer in the affirmative when he asked if Fiorella and I could interview him in the deep Andes of Peru. We knew that it was going to be challenging to prepare for this interview due to final exams, the holidays, and the remoteness of the area, but we happily accepted this exciting challenge.

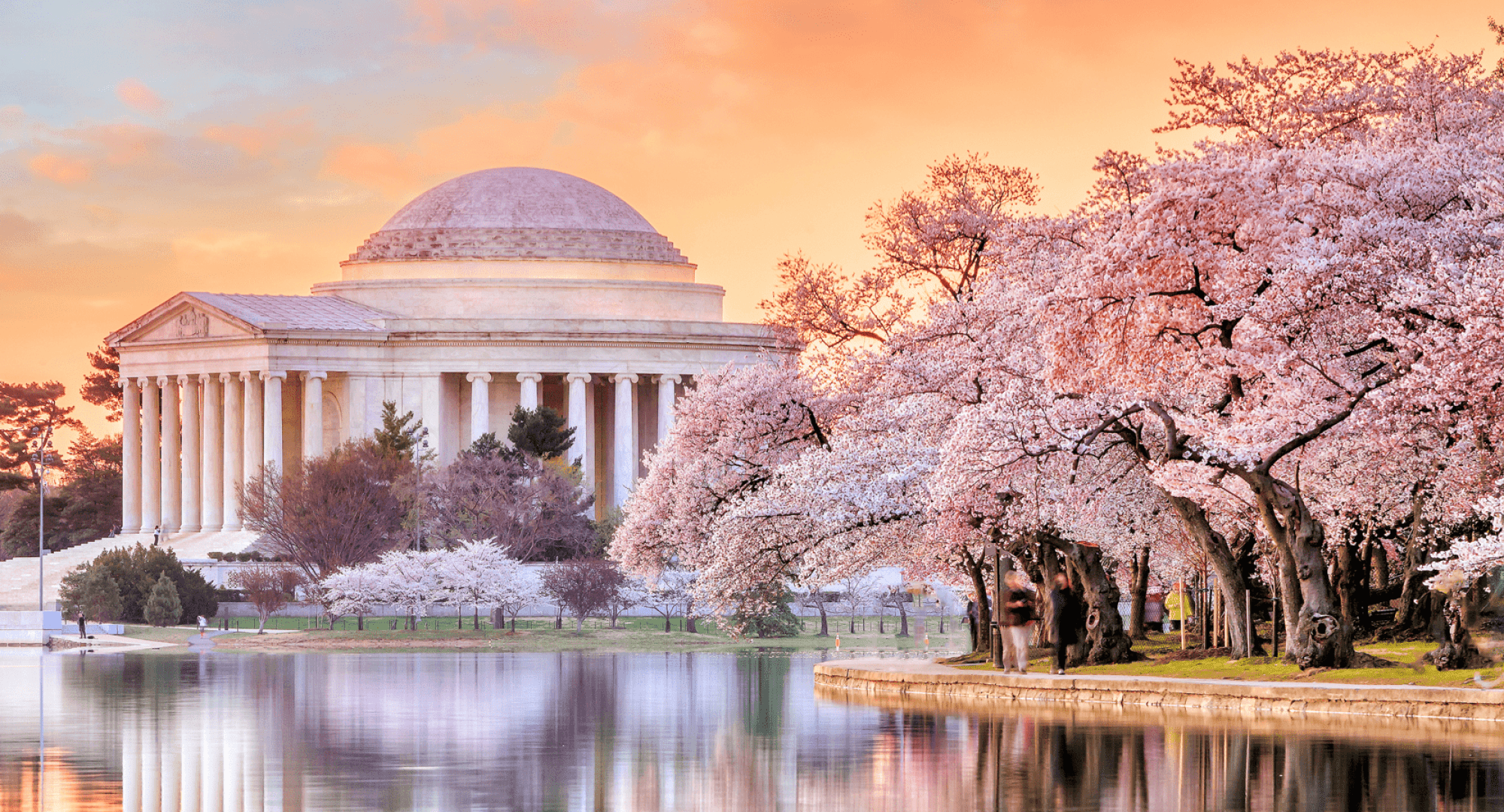

Credit: Walter Hupiu Tapia / Germanwatch

Our paths went beyond urban Lima, where we are from. Our journey took us to the heartland of the Andes, where we were welcomed by Indigenous communities with smiling faces and who carried tales of struggle and triumph, echoing the silent activism of a community trying to protect its ancestral lands from climate change. Within this context, we finally met Saul, a figure whose spirit resonated with the surrounding mountains.

In this three-part series, Part I introduces the story of Saul Luciano Lliuya. Saul may not be as well-known as fictional Marvel heroes, but he has become a hero of the climate justice movement. Many have referred to Saul’s fight as a fight between David and Golliath; the fight of a humble Peruvian farmer against a giant German corporation. Saul’s experience is the story of an individual whose way of life has been threatened by climate change and whose tireless efforts to protect his way of life in the Andes have earned him well-deserved recognition as a champion for climate justice.

Saul’s battle seeks to ensure the safety of his family and community from a potential deadly flood. A glacial lake above his city has grown considerably. In the event of a flood, Saul’s house and a large part of the city of Huaraz located below the glacial lake would be threatened with a catastrophe that could affect up to 50,000 people.

In 2015, together with Greenwatch, Saul sued RWE, a German energy company. RWE has never had any operations in Peru, but it is one of the top 10 sources of carbon and methane emissions in Europe.1 RWE accounts for about 0.5% of the cumulative global industrial emissions of carbon and methane between 1751 and 2010, an impact that transcends national boundaries.2 In Saul’s opinion, since RWE is responsible for 0.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, it should be responsible for 0.5% of Huaraz’s flood.

Based on the lack of support he anticipated from Peruvian courts, and with the help of Germanwatch, Saul decided to file a lawsuit in the German court system. In 2015, Saul filed the suit in the District of Court Essen, and in 2016 the court dismissed the claim.3 The court rule that there was a lack of a “linear causal chain.”4 Saul, however, appealed to the Higher Regional Court of Hamm, where his case was admitted, allowing it to proceed to the evidentiary phase.5 Although Saul is seeking $20,000 in damages, this amount is trivial when compared to the precedent that can be established by his case.6 If he succeeds in this case, Saul would be able to hold a major corporation accountable for its contribution to global climate change, which would pave the way for future lawsuits against similar significant source of greenhouse gases in the future.

This interview was more than a conversation; it was a dialogue between tradition and the urgent need for environmental advocacy.

- What sparked your interest in glaciers?

First of all, I would like to thank you for your visit. Peruvians rarely visit us; I remember only two Peruvian visitors from Lima and Huaraz. Foreigners are usually the ones who visit us.

Well, I grew up here. Specifically, I lived in my father’s house upstairs, two minutes from here. Growing up in the countryside, and helping your parents on the farm, you become aware of how things were before. I observed that the glaciers were covered with snow; it looked very white, and little by little there was less snow on the ground. It is not only my observation, but also something that my neighbors and friends discuss when we meet. Nevertheless, we are more concerned with the issue of water. We’ve been told that we will no longer have water if we don’t have a glacier. It is a daily conversation.

I attended kindergarten here and primary school in Huaraz. By then, my parents had built their homes, and that’s how I started studying in Huaraz city. From Monday to Friday, I spent five days in Huaraz city, and on Saturday and Sunday, I returned to the countryside. As time passed, I graduated from high school and began thinking about my future. I studied to become a mountain guide in 2002. I contacted experienced guides who had worked for years. As I began trekking and mountaineering in the mountains, I heard conversations about the glacier disappearing. I have been working on this issue for 20 years after studying for three years.

People working in tourism, including muleteers and guides like me, are very concerned. Each year when I returned to the mountain, I observed that the glacier retreated, and more and more rocks were left behind. We all knew the news about global warming. We know that glaciers from the Arctic are melting as well and, due to climate change, the sea is rising.

In 2014, I met with a friend, José Roca, who came here. I think his parents or relatives are from Huaraz, and by that time he was living in Cajamarca. Jose introduced me to Germanwatch, in December 2014.

- Were you able to express your concern for glaciers to José when you met him? Did José let you know if he would be introducing you to Germanwatch? How was this second step taken?

When José Roca informed me that some Germans were arriving, I assumed they would be clients because I work in tourism, and I could offer my services as a guide. They arrived because they had heard of the Palcacocha Lake, which is located up in the mountains, after traveling to Lima for the COP 21 conference. Having spent twenty years in the mountains, I treated them just like any other visitor. I spoke with them, and they informed us that we could file a lawsuit. I understood that certain industries pollute more than others, but how could we hold them accountable by suing them? I had no idea if it was feasible. With the assistance a translator, we had a conversation with the German lawyer.

After discussing the alternatives with the attorney, I was informed that there was only a 10 percent chance the judge would accept the lawsuit. Since we had nothing to lose, we filed a lawsuit to stop the deglaciation. Everyone in this area was concerned about the deglaciation, warming, water scarcity, and flood risks because this region has a history of alluvium, including the alluvium that destroyed part of Huaraz in 1941, which claimed many lives and devastated a portion of the city. Although the phrase “climate change” was not being used at the time, the phenomenon had already started. Lagoons were created as the glaciers melted. The lagoons grew and because the moraine—which in certain cases was just soil instead of rock—could not contain the water, it spilled.

- How does deglaciation have a direct impact on you and surrounding communities?

In terms of farming, my parents claim that in the past they didn’t apply insecticides or fertilizers. The rains came and things went according to plan. However, as evidenced by the recent El Niño events, this is no longer the case.

Muleteers who work in tourism will tell you that there used to be more rain and more grass in different ravines, but now there is little grass, and if you did not use insecticides or synthetic fertilizers in the fields, you would not be able to grow grass. Another example is the worm, which virtually prevents you from harvesting the potato if you don’t spray it with insecticide. In the past, you could store potatoes for a year, and they wouldn’t rot, but now the Iñaku worm eats them in a matter of months.

Another example is corn, which you could once store for up to three years without any problems. However, these days, the moths are consuming it in a matter of months, and in this instance, the reason is that the climate is too hot.

Another problem is water. It used to be abundant. In the past, this village could drink water from a spring that never dried out and it had a wonderful taste because it was pure spring water. However, during the rainy season, the puquial is full, but as June and July approach, it dries up entirely. The river water is being piped, which just supplies this city. It’s important to think about population growth as well.

When it comes to irrigation, there are restrictions now. In the past, you could irrigate because there was an abundance of water, and conflicts between farmers for water were uncommon. However, these days, conflicts arising from the desire for more water are common due to the low water supply. We use canals to get water from a stream. Although the water has always been present, we have noticed a lack of it over the past two or three years. This is not unique to our area, though; friends outside the area face the same issue. We need to moisten the soil to plant for the next year, so we must alternate who gets water. There are years when the rain comes on time, there are years when it is late, and there are years when there is not rain. This is part of the global warming and El Niño phenomenon.

- Concerning the lawsuit you filed, I read in an article that they came to investigate from Germany to verify whether what you said was true. Did they come from Germany to conduct an investigation?

Yes, the first lawsuit was filed in a local court in Germany. The judge did not accept the lawsuit.

We met with the lawyer. She informed me that the arguments presented were very weak. This gave us the option of appealing, although I felt apprehensive because it is a very dangerous thing to sue a large company. Consequently, we appealed to the Higher Regional Court of Hamm, where the judge accepted the lawsuit.

We received a visit from them. They came to Huaraz, visited the lagoon at risk, and my house which is in Nueva Florida, so yes, they came here.

- Did you ever feel intimidated for being against, as you mentioned, such a large corporation? Did you question whether you should proceed with the lawsuit? I see that you have a lot of passion for saving the Andes.

Yes, ever since they proposed the lawsuit, I was a little afraid but never intimidated. Here, the concern is about water and the glacier, and if we did nothing, despite having the opportunity. You would do it, too, if your mountains were disappearing before your eyes. It’s something anyone would do, right?

- You’re like a hero of the glaciers. And we were just talking about how important your international presence is with the NGO, but here in Peru, have you felt the support from anyone, any institution, or organization?

Yes, here in Huaraz, we have the authorities, for example, the National Water Authority (ANA). We also have the National Institute for Glacier and Mountain Ecosystem Research (INAIGEM), which is responsible for glacier research. They have scientists who are monitoring all the mountains and the lagoons. At that time, there was also an environmental office in the regional government. They understand better than we do because, for example, INAIGEM has all of the data on what is happening with the mountains. They provided the data to us. For example, when the judge visited, he called INAIGEM, ANA, the Civil Defense of the local government, and the regional government as well as the engineers, and they gave their version. There is deglaciation, and there are lagoons that have grown due to deglaciation, and that is a danger to the city. In that way, the authorities, the governments, and the officials at that time confirmed that the lawsuit was valid.

- From a cultural point of view, understanding the mountains as Apus7 and glaciers as Apus, how do you think deglaciation affects that? Or do people not relate to it?

It’s more about water. People say, as I mentioned, “Without glaciers, we are like Rajuntsi Canatsu, meaning we no longer have glaciers. People like me consider the mountain as our own, it’s like it belongs to us or is part of us. We feel that way. It’s like another family member.

- To us, you are a hero and a global inspiration. That’s why we would like you to provide some kind of recommendation, a message that you would like to give to other people who can speak up, who are seeing what is happening in their community, in their country, and feel that they cannot stay idle. What would you say to these people who say, “What can I do?”

Well, we are all here, part of wherever we live. We are all part of the planet. And if they can do something in different ways, they should do it. For example, you as lawyers who develop laws also have the obligation to use your knowledge. Like me here, as a farmer, as a mountain guide, I felt and saw what was affecting us. So, if an opportunity arises, you must do it. So, the message would be: Wherever we are, we must contribute, whether as lawyers, engineers, scientists, farmers, etc.

- What massage would you give to those in positions of power who can make decision on these issues?

Those in power have mostly reached power through election, by the vote of the majority. Well, voters are responsible. Here, for example, in the last elections, there was a candidate talking about water harvesting and climate change. The other candidate didn’t talk about that and talked more about mining. Mining is not bad, but as someone who knows about climate change, I voted for the candidate talking about climate change. So, we, who put the authorities in power, must also demand. In the end, when candidates come to power, they no longer want to hear about the issue, so it’s a bit complicated.

- Have any lawyers helped you? Or has the press come to cover your case?

Once Channel 4 came. And some members of the press, for example, Mula interviewed me. Ojo Público, El Comercio, and La República also did.

- Peru is centralized, and everything is in Lima. Would you like to say something to the people in Lima? To people who have power in Lima, a ministry? What could you tell them to help you?

Well, they, as authorities, have the duty to work for everyone. All authorities know about the problem of climate change and the problem of Huaraz. So, they should work on that, mainly for adaptation. Because to recover what has been lost is impossible; it’s irreversible. And all that remains is to adapt, and the authorities must work on that.

- José mentioned a project to obtain funds for building a dam to protect against possible flooding from Palcacocha Lagoon. Can you provide more information on that proposal?

Yes, this is an issue. The flood happened in 1941. Three years later, the government ordered the construction of a dam, but only one, and then another flood occurred, damaging another side, and they built another dam there. Since that year, the glacier has been gradually melting, and the lagoon remains. We’ve been going through this for a long time, and every authority that comes in always talks about building a dam. When there was a flood, people got scared, the news came out, and only then did the authorities say, “We already have the profile, we have the study, we will build a dam.” Presidents of the region always speak like that, and until now, they haven’t done it. There’s only a provisional siphon, and there are about 10 pipes that control the water level below.

- I think that system is the drainage of the water level so that it stays low, right?

Yes, it’s also about water. From Palcacocha Lagoon, a river flows, and from that river, Huaraz takes its water. It’s a matter not only of the risk of flooding but also of water.

- So, it’s a call to the authorities in Huaraz to get to work and not just promise but fulfill what they promise.

Certainly, to find ways to supply water to the people.

- And what has the reaction been from the German corporation? Have they reacted in an antagonistic or negative way towards you?

No, so far, the company has not had contact with me. I have only had contact with the lawyer and with those from Germanwatch. We hope there are no threats or reprisals.

Thank you very much, Saul. We are so grateful that you have shared this time with us and given us the opportunity to get to know you a little more and learn more about your struggle. You are not alone; you have many people supporting you who will be watching each of your achievements in this litigation process. We know that achieving justice takes time, and that can be frustrating. As lawyers, we understand that because many processes are very formal and time consuming. We know that what you will achieve will not only be positive for Peru and for you, but also for many communities around the world and the global legal community in planning future strategic climate litigation.

“You said something that I will take with me. When I asked you, “What led you to do this?” You said, “Well, I’m seeing the change, I have evidence, and anyone would do it.” But not everyone did it; you did it. If everyone would do it, you wouldn’t be here talking to us. We could be interviewing someone else, and the fact that you took this first giant step means a lot. In an article, I read, they compare your fight to a “David’s war against Goliath.” You are David, and they are Goliath because not everyone confronts such a large corporation and has the determination to do what you have done. You are truly an example, and your courage and determination inspire me.” Maria

“Indeed, you are an example for your family and to your children. I believe they must be proud to have a father like you. And as Peruvians, we are very proud to say that Mr. Saul is Peruvian.” Fiorella

Thanks for the visit, Saul.

Fiorella Valladares LL.M. 24, Saul Luciano Lliuya, and Maria LeLourec J.D. 24.

- Camilla Hodgson, Who pays for climate change? The Peruvian suing a German utility, Financial Times (July 5, 2022).

↩︎ - Id. ↩︎

- The Climate Case: Saul vs. RWE, Germanwatch (May 30, 2023). ↩︎

- Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG, Climate Change Litigation Databases. Since his case is treated as a tort case in German courts, the court could not discern between particular greenhouse emissions and particular climate change impacts. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Gloria Dickie, Explainer: Climate activists, companies lawyer up for courtroom battles, Reuters (Nov. 23, 2023). ↩︎

- In the ancient religion and mythology of Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, Apu is the term used to describe the spirits of mountains and sometimes solitary rocks, typically displaying anthropomorphic features, that protect the local people. The term dates to the Inca Empire. For more information, see “What Makes an Apu an Apu?” ↩︎

Maria LeLourec

Juris Doctor Candidate at The George Washington University Law School.