In late May, protestors descended on Istanbul’s Taksim Gezi Park. At first, there was a small sit-in over re-development plans that would have it, one of the few parks in European Istanbul. After months of unsuccessful petitioning to save the park, activists took to camping out there to prevent the demolition. Police removed them by force, setting their encampment on fire in the process.

The state’s aggressive response was met with outrage as images of the police action spread. This brought far more protestors to the park. They expressed a general dissatisfaction with the government’s increasingly restrictive policies and actions. Some were displeased with new limitations on alcohol sales during certain hours, increasing censorship and bans on public displays of affection. The government deployed punitive measures against dissidents and those insulting religion.

Turkey’s contemporary politics is defined by a delicate, but tilting balance between the religiously-inclined socio-politics of the dominant AK party and the deep strain of Kemalist secularism. The latter is reflected constitutionally, going back to the founder of modern, post-Ottoman Turkey. It’s a set of nationalist values entrenched institutionally in the military, which plays a vital role in shaping Turkey’s polity, as well as among a good portion of the Turkish population. The AK party, however, was re-elected several times by a majority of the country, and therefore enjoys something of a popular mandate to legislate socially conservative policies. The modernist, westernizing vision of Turkey is at odds with the outcomes of democratic process.

This turn in political culture matches Turkey’s pivot in foreign affairs, from its abandoned westward aims of joining the European Union to playing a more active role in Middle Eastern international relations.

Protests that began over a very specific qualm — the razing of the park — quickly grew to larger movements of general dissent in others parts of the country. Labor strikes, mass protests and organized action by professionals and academics confronted the government. Riot police frequently used force and instruments such as tear gas, clubs and other weapons to disperse crowds.

Turkish President Abdullah Gül recently praised the original sit-in for the values it espoused, though he differentiated them from the later agitators who he saw as perpetrating violence. In response to the accusation that the state’s response was overwrought, he said its tactics were quite consistent with the types of response in other countries. Rather than seeing these as amounting to a crisis of legitimacy, he sought to normalize the protest and the state’s response: “These kinds of problems are mainly democratic and developed countries’ problems. Turkey’s problems have come to a point resembling these.” In other words, these are #firstworldproblems.

President Gül’s claims are hard to square with the extent of violence that ensued. Freelance journalist Ahmet Sik said: “I have worked in war zones but Taksim was terrible. The security forces were hunting people down. Media personnel are targeted twice over. By demonstrators who think they are siding with the government and not covering events properly. And by the security forces, who deliberately fire at us.”

I am sure reasonable people can disagree to whether this is hyperbole or not, but one less ambitious question could be: How capable was foreign and Turkish media in reporting the story?

At a recent one-day symposium at Dublin City University, Esra Doğramaci spoke on this exact topic. She highlighted numerous, systematic errors in traditional news coverage, and showed how social media helped correct misreporting.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajxV737Voso&w=640&h=480]

Her most stinging critique was that foreign media reported these protests within an “Arab spring” frame. This suggests a revolutionary purpose aimed at regime change, rather than towards specific policy reforms. Referencing the protests as “Turkish Tahrir” was emblematic of “sensationalism and misinformation.” The numbers, the eventual unanimity, and the scale of government repression did not match, making the Arab spring frame fall flat. As one analyst suggested the underlying issue is identity, and that Kemalism was a “spent force” while long-suppressed religious politics are emergent.

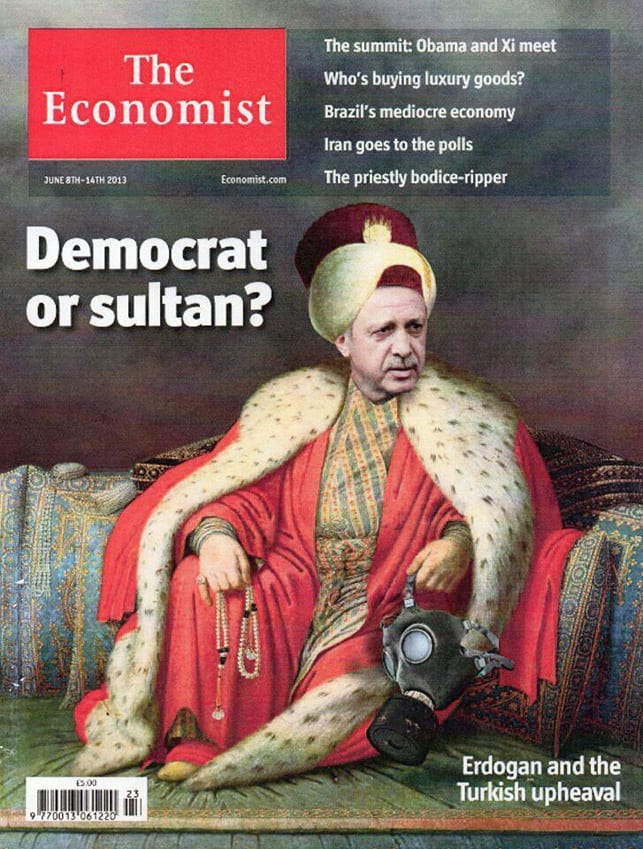

Not only did news media fail to explore this more relevant historic context, but they offered reductionist and ahistorical parallels instead. She points out The Economist cover that superimposed Prime Minister Erdogan’s face on an Ottoman Sultan’s body.

Doğramaci pointed to blatant acts of misreporting, from identifying a mass audience for the Prime Minister as an anti-government protest, to outdated photos of an injured child, to articles gauging national opinion based on interviews with ten Turks. One rumor that the government shuttered cell phone service was reported, but shown by a social media user to be false. She attributed these, in part, to the problem of producing “news requiring least effort.” Social media users, could correct the record and push journalism to be better.

There are, however, other systematic issues. The Turkish spring frame, could reflect a lack of familiarity with the idiosyncrasies of Turkey, such as the deeper tension in its changing political culture. Editors or journalists may just collapse it in with the set of Arab countries that saw uprisings starting in late 2010 — Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and Syria. Or, it could be a frame intended to grab more page views: a “hook.” That certainly seems to be the purpose of magazine covers, after all.

Covering it poorly is probably better than not covering it all. CNN Turk, Doğramaci mentioned, famously ignored the story all together, showing a documentary about penguins instead of the first protests. CNN International was more on the ball, refusing to get scooped. The CNN Turk documentary led to a fun protest meme. The penguin became the protestors’ new logo for neglectful media non-coverage.

One wonders, however, whether we can just fully blame faulty media coverage. The Turkish government’s high rate of convicting and imprisoning journalists won it the nickname “world’s largest prison for journalists.” When Reporters With Borders deems a country that, one wonders how state policy and pressures interfere with journalists’ access and ability to report competently on important stories, such as these protests. Documented reports of intimidation and censorship of journalists suggest government policy can also create reporting skews. One impact is it discourages reporters from covering it. This could be the reason CNN Turk was slow to the subject.

Turkish repression of media is so extensive that it immediately calls into question President Gül’s assessment of the protests and the state response.

Despite the potential for social media users to circumvent traditional state instruments, such as its criminal law, the thick censorial regime would be very likely to impact how key moments in Turkey’s struggle for a new direction are presented, making the veracity of information more difficult to decipher. Far from excusing sloppy journalism, unimaginative metaphors and skin-deep analysis in news media, pointing to the lack of press freedom in Turkey is an essential first step towards helping outsiders better understand what is happening within.