“It is important to be ‘seen’ – being there physically matters if you want to be a successful diplomat,” noted Ambassador Robert Ford at the 4th Annual Walter Roberts Lecture last Wednesday.

Public diplomacy (PD) professionals have long emphasized that the last few feet of communication can make a huge difference in public perception and engagement. Ambassador Ford demonstrated clearly, through fascinating accounts from his tours overseas, that public diplomacy is essential to successful diplomatic work. Countering the notion that diplomats work behind the closed doors of government, the former U.S. Ambassador to Syria and Algeria emphasized the role of active public diplomacy in breaking down barriers and conveying policy messages.

Here are the five lessons that Ambassador Ford referred to in his lecture that he had learned were important for successful public diplomacy:

1. It is important to be “seen” – being physically there matters

We often forget that many people around the world have never met an American, much less an American diplomat. People in Syria, Egypt, China or Brazil have a vision of Americans that is often formed by television programs, movies, websites, the news or the anecdotes of friends who may have come into contact with an American. One “ugly American” can color the perception of a whole village; conversely, one open, warm and understanding American student or teacher can influence an entire student body at a university.

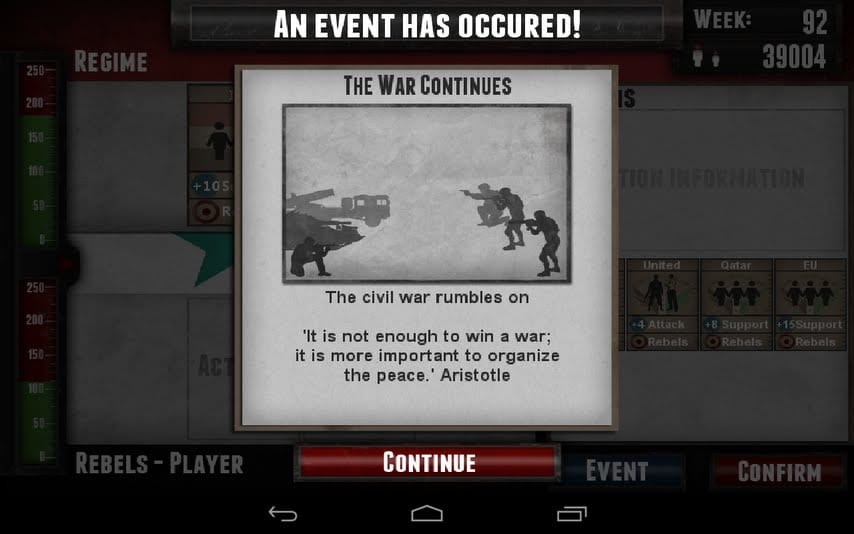

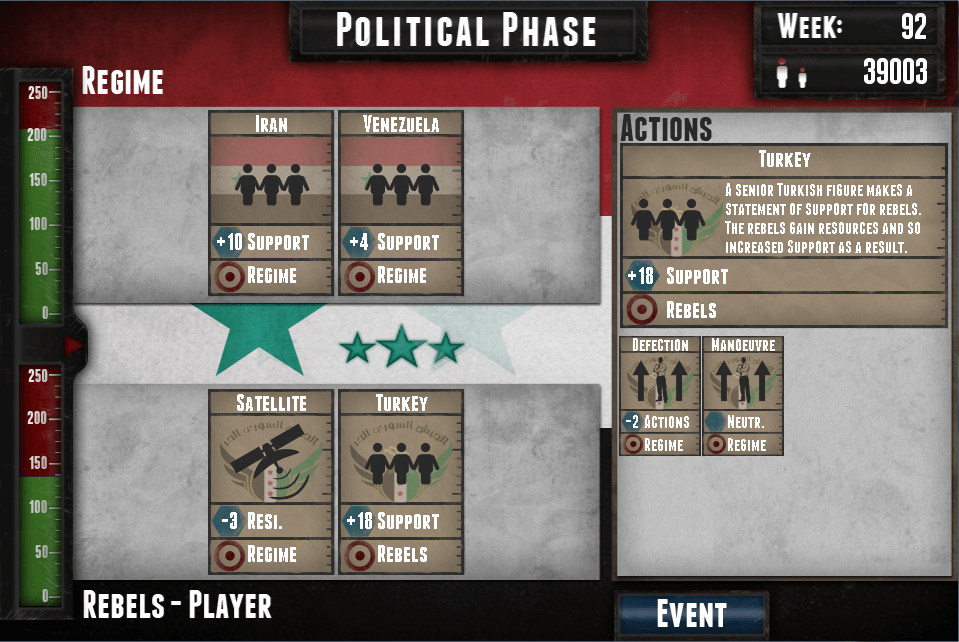

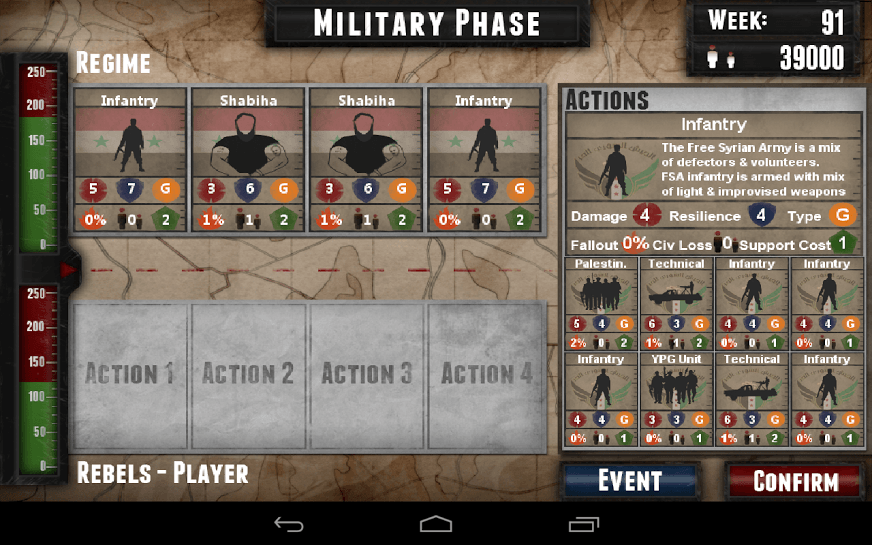

Ambassador Ford noted that his visit early in the Syria conflict to Hama to witness local demonstrations and listen to the points of view of all parties had an enormous impact on the people he met and policy makers in Washington simply because he was physically there. He believed that his visit sent a message to Syrians that the U.S. supported the right to freedom of expression and assembly.

Over the years, as a public diplomacy officer in the Foreign Service, I have worked with many ambassadors. We have debated together the merits of “being there” to convey a message that actions could express more forcefully than words. Should the ambassador attend a funeral of a prominent dissident? What about attending the opening event at a film festival that was airing anti-American films? Would it be effective to speak at the opening of a Special Olympics event to highlight our concept of equal access for all? Or, to demonstrate respect for local culture and religion should the ambassador visit an historic mosque, church synagogue or temple?

As I accompanied these ambassadors, I met people who would consistently note how important it was for the U.S. to send the message of support for human rights, tolerance or inclusivity through the presence of our ambassador. No matter what the activity, just “being there” always had an impact and conveyed the essence of American values.

2. Reach out to regular people

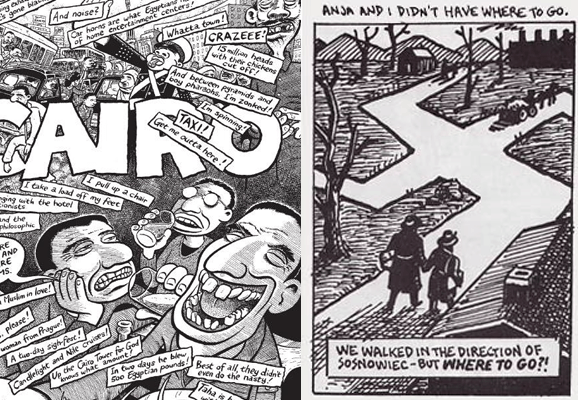

At my last post in Cairo, we debated the merits of what we called “grassroots public diplomacy” or reaching out to regular people, Ambassador Ford’s number two on the list of lessons. But, who are “regular people” and why are they important? Traditional diplomacy has focused on relations between governments and government officials. For centuries, diplomats met in offices at foreign ministries or at formal events. Over time, diplomatic activity expanded to include critical influencers of foreign policy or public opinion, such as journalists, writers or cultural figures.

Regular people are basically everyone from the doorkeeper, elementary school teacher, and NGO worker to the owner of the local café. They are important because if you take the time to meet them, discuss and listen you can really understand the local economy, political situation or mood of a country. And, in societies where people believe their neighbors or family members more than the evening news broadcaster, your meeting could be significant in influencing public opinion.

I still remember the eyes of a mother from a poor community in Tunisia who took me aside at a student graduation ceremony to note that our English language after-school program had kept her son off the streets and out of trouble. We sat, surrounded by other parents, as she discussed her dreams for her son and I presented our exchange program opportunities. Taking the time to listen changed the entire dynamic of the event for everyone at a time when criticism of U.S. policy on Iraq was on the front page of every paper.

3. Keep up with technology

Ambassadors are notorious for their discomfort with the latest in social media. First of all – by the time you get to be an ambassador, you are usually older than the rest of the staff at the embassy (apologies to ambassadors!) Persuading an ambassador to tweet, use Instagram, or blog usually results in the Public Affairs Officer and staff being assigned another task.

The point is not whether the ambassador or other diplomatic staff knows how to use the latest technology – it is whether they understand how to incorporate it as a tool for planning and strategy in communication and outreach. In his speech, Ambassador Ford highlighted the use of social media in a restrictive communications environment. When he could not reach out to present the U.S. administration’s point of view on the treatment of Syrian demonstrators, he could still get out the word via Facebook. Whether it is Youtube, Twitter, Facebook or another platform preferred in a specific country, social media allows a diplomatic mission to reach large numbers of people.

In Cairo, the embassy currently has over 850,000 Facebook fans. They post questions and comments in Arabic and English, sign-up for events, or participate in competitions. Once we asked, who are all these people? And in keeping with point number two, an event was organized to meet 100 of fans. They came from all over the country and from every strata in society: students, businessmen and women, alumni of exchange programs, journalists, teachers… the list was endless. They all had one thing in common: an enthusiasm to engage. And in keeping with point number one, some of them had never met an American and now there was an opportunity for American diplomats to “be there.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ip_TZoo7Uw]

4. Don’t overuse access to the media

The usual modus operandi of all ambassadors is to get as much positive press coverage of U.S. policy or diplomatic activities as possible. Public diplomacy sections, especially the press officers, spend hours strategizing on how to make this happen. They work hard to figure out how to use media opportunities to convey important messages to local publics. And, the press officer will also arrange events where the ambassador and other officers have the opportunity to listen to the insights and opinions of local press.

Ambassador Ford, however, reminded the audience that more is not always a good thing: “Don’t overuse access to the media.” Some messages are better delivered in person behind the closed doors of a foreign ministry or in a speech to a specific audience of businessmen. The message, when delivered via the media, can result in host government backlash if it is unexpected. Or, because you just made the issue part of a public debate – it gets buried by the response of multiple and conflicting articles and opinions.

Public diplomacy officers are always aware, as well, that journalists want access to the ambassador just as much as we want to get out a good story. Sometimes that results in the equivalent of journalistic “blackmail” – “I am doing a story on X and it will run tomorrow. Can you give me a comment?” Or, they run a story and when you call to note they have the facts wrong – then the journalist asks for an exclusive to set the record straight.

So, use media access judiciously and with awareness that it is the right tool for the purpose.

5. Don’t underestimate the power of outreach and soft power.

As a public diplomacy officer, I was heartened to hear Ambassador Ford note that soft-power and outreach can have a tremendous impact on foreign publics. He recounted a story of visiting a university in Algeria. He told the PAO (Public Affairs Officer) to keep it low-key since he knew that U.S. policy in Iraq was not very popular at the time. When he arrived at the university, he was overwhelmed by a large and very public welcome. It turns out that the English language and skills building programs established by the Public Affairs Office and implemented by partnerships with U.S. universities where tremendously popular and successful. The university president wanted more! I could recount more stories where finding common interest has resulted in politics being put aside – but, I am running out of space. These blogs are supposed to be under 800 words and I am over!