Nelson Mandela leaves us in December, a season of holiday hope. His passing inspires us to reflect on his spirit of hopefulness and optimism and his role as a public diplomat.

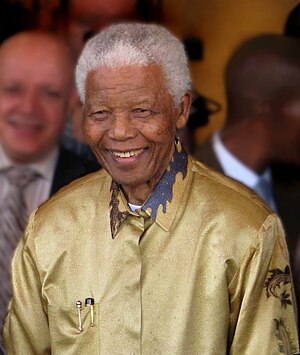

I first met Nelson Mandela on February 15, 1990—four days after he emerged from 27 years of imprisonment in South Africa. I was there as a producer for ABC News Nightline. Mandela had agreed to give Ted Koppel a one-on-one interview. What I remember most when he arrived for that interview in Soweto was his gracious smile, his warm but firm handshake, and the elegance of the man who towered, physically over Koppel but still managed to look him in the eye as an intellectual peer.

So much has been written about Nelson Mandela, but what is rarely said is that he is the epitome of public diplomacy—one of those rare individuals who understood the power of people to move nations and ideas. Mandela was a connector, bringing people together from all walks of life—rich, poor, skilled, unskilled, men and women, athletes and artists. He had the gift of gab and the kindness that radiated a room.

At a time when his own country could have descended into far greater violence and societal division, Mandela instead steered his nation with words through a transition from apartheid rule that was marked by a commitment to national unity and peace even while boldly confronting the evils and divisions of its past. Mandela inspired people and governments the world over seeking peaceful and just resolution of conflict.

A good public diplomat like Mandela understood that for a nation to truly heal, its people must reckon with the past and with each other. It is why on June 28, 1995, Nelson Mandela announced the creation of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. That act alone turned history into the present and future South Africa and elevated his story of struggle over injustice and adversity. As he said in his inaugural address as president of South Africa on May 10, 1994, “We commit ourselves to the construction of a complete, just and lasting peace.” Personal commitments sometimes mean more than treaties and documents, and Mandela knew that his word was his oath.

President Mandela, your history is our global history and you remain a lodestar shining brightly like your beautiful smile. We all wish you peace in this season of peace.