Although it hasn’t garnered much attention in the U.S., tensions are high and escalating between the Catalan region of Spain and the national government in Madrid. The latest incident came Sunday when Spanish Defense Minister Pedro Morenes said that the military was “prepared” in the face of “absurd provocations,” presumably referring to recent calls for Catalonia’s secession from Spain.

The friction provides a window into the intriguing but under-studied topic of what is sometimes called sub-state public diplomacy. Like many sub-states – e.g., Quebec and Scotland – the Catalan government has recently embraced public diplomacy as a means toward promoting their region and pursuing their own economic and foreign affairs goals.

Yet if those goals shift to include independence, this could have profound and challenging implications for how Catalonia conducts its public diplomacy.

First, some quick background for those not familiar with the Spanish case. Following the death of the Fascist dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, Spain was divided into 17 autonomous regions, with each controlling education, health, and cultural policies within their borders, while other policy areas remained under the purview of the government in Madrid.

Yet Catalonia has a strong independent streak rooted in the fact that it had been autonomous for centuries before being conquered by Spain in 1714. Catalans are a notoriously proud people, with their own language and a strong cultural history that includes Miro, Picasso, and Gaudi, to name just a few luminaries.

Catalonia and its capital, Barcelona, also represent a driving force in the Spanish economy. This means that Spain needs Catalonia at least as much as the other way around. This is as true during the terrible economic crisis both are currently enduring as it is in good times.

In fact, it is the economic crisis that some say has fueled the rising secessionist talk from Catalans in the past year. A lack of jobs and revenue has rekindled questions amongst Catalans about why their tax dollars should go to aid poorer regions of Spain, while simultaneously making the rest of the country all the more dependent on the region’s contributions.

In November, Catalonia held elections that were seen in part as a de facto referendum on secession, especially after a huge pro-independence rally in September. The outcome of the vote led to the forming of a coalition between Catalan President Artur Mas’s center-right CiU party and the more leftist and pro-independence ERC party.

Tensions escalated in mid-December when Spanish Education Minister Jose Ignacio Wert put forth an education reform plan that would restore Castilian Spanish to primacy in all classrooms. Catalans saw this as a naked attempt to eliminate the Catalan language, which is currently taught throughout the region alongside Spanish and is seen as integral to Catalan cultural identity. Franco, for instance, had banned the speaking or teaching of Catalan during his nearly 40-year reign, just as Spain’s Philip V had after the 1714 conquest.

It would be hard to exaggerate the anger that Minister Wert’s proposal engendered amongst Catalans. I happened to be traveling in Barcelona that week, interviewing government officials and others, and the outrage was passionate and palpable. Pro-independence flags flew everywhere and huge rallies were held in protest.

“Even with civil guards in the classroom, school children will not stop studying Catalan,” roared the Congressional spokesman for the ERC. “You are going to come up against a nation ready to defend its children. Don’t you dare touch our children. We’ve had enough; we won’t obey.”

Not to be outdone, the CiU congressional spokesman evoked Spain’s history of trying to silence Catalans: “Phillip V tried to put an end to Catalan and later Franco, but they didn’t succeed.”

Within days, CiU and ERC reached an agreement to hold a referendum within two years on independence. On New Year’s Eve, Mas gave a pro-independence speech in which he said that Catalans “want to build a new country.”

Catalan independence flags.

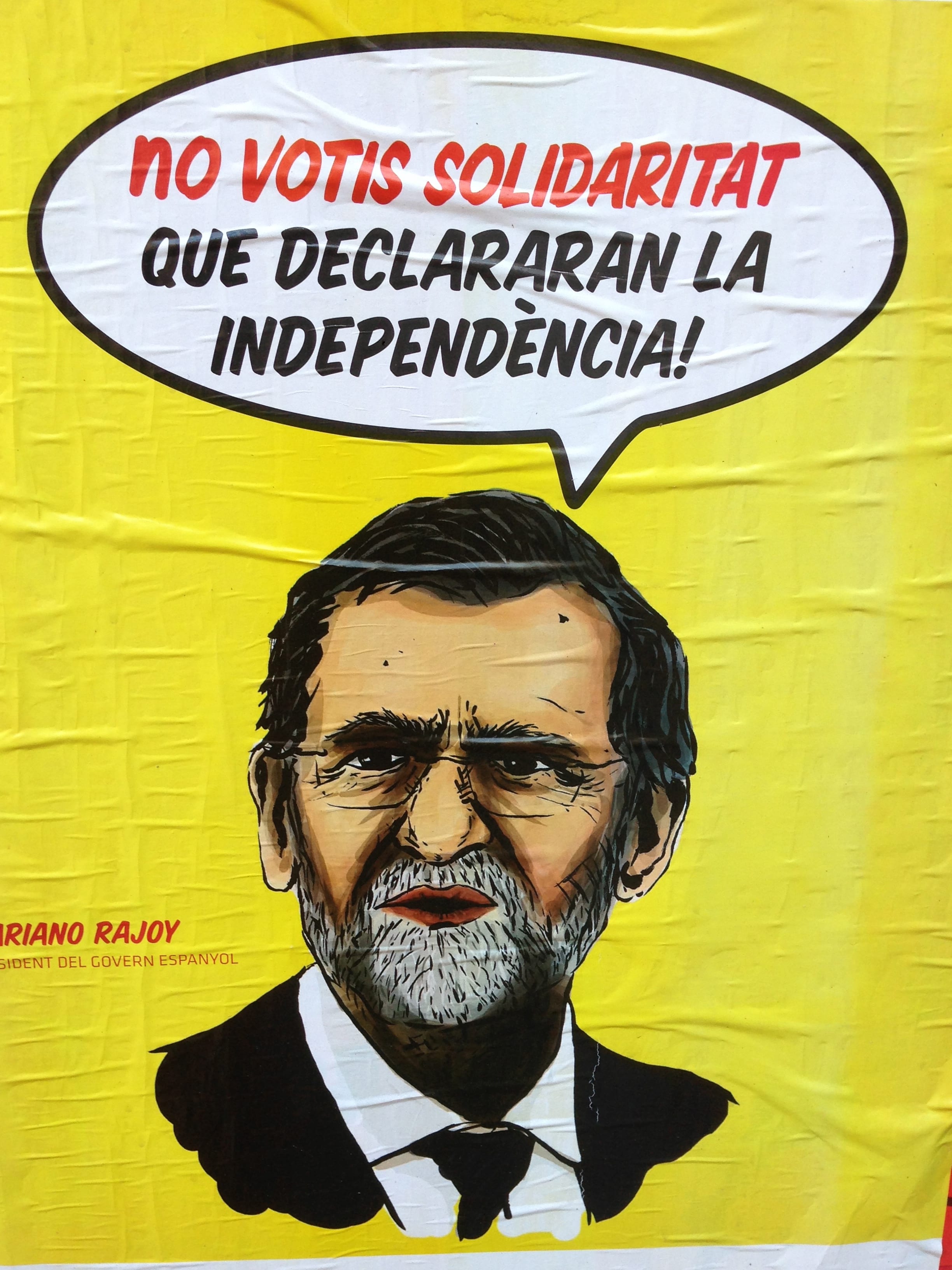

Although Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy tried to calm things by saying he’s open for dialogue, he made clear that this would be through the prism of the Spanish Constitution, which does not have a provision for secession.

This, though, is where Catalonia’s public diplomacy efforts become an interesting part of the story.

In 2008, the Catalan government began embracing the idea of public diplomacy as part of a larger foreign affairs strategy, and PD represented a core part of the region’s five year (2010-2015) strategic plan.

The PD efforts take several forms, including exchange programs and cultural events such as last year’s Miro exhibit at the National Gallery. But a major component involved creating Catalan delegations in six cities around the world: London, Berlin, Paris, Brussels, New York, and Buenos Aires (which recently closed). Madrid was never thrilled about these delegations – after all, Spain has their own embassies in all of these countries, so why spend the money to have a notoriously troublesome region doing its own PR? But the national government went along on the condition that the delegations simply engage in pro-Catalan work, not engage in any anti-Spanish rhetoric, and not discuss the tensions between Barcelona and Madrid, much less independence.

The recent outbreak of separatist sentiment, however, may change the nature of the delegations’ work, and Catalan public diplomacy generally. Rather than avoiding the topic, or promoting an image of harmony with Madrid, the Catalan government may see a need to start using the delegations to more proactively adopt an independence frame in their rhetoric and outreach.

This makes sense if you start from a premise of future independence. If that is what lies ahead, then Catalan public diplomacy needs to start laying the groundwork for having the rest of the world think of Catalonia as independent and unique. This would go hand in hand with a larger policy of gaining EU and other international support for not only secession, but future membership in the EU. It is worth noting that according to one government official I spoke to, President Mas has made more trips in the last year to Brussels, the EU headquarters, than he has to Madrid.

At the same time, this is a risky strategy, because ultimately Madrid exercises some control over Catalan purse strings (there is currently a dispute over payment transfers, for example). It could move to punish the region – and perhaps apply pressure to close the delegations – should they be seen as promoting independence. And if the Catalans aren’t able to secure independence, then they will have done much to poison relations with Madrid.

In the meantime, the Catalans are also embracing strategies aimed at gaining more favorable coverage in the international media. Like all sub-states, a major problem Catalonia faces is that virtually all of the international reporters covering Spain are based in the capital of Madrid, and hence are inundated with the national government’s frame of Catalonia. To remedy this, the Catalan government has been creating more opportunities for those journalists to visit the region (conferences, for example). Some officials told me that they have noticed more balanced coverage (from their viewpoint) as a result.

Similarly, the Catalan delegations around the world will need to develop a proactive media strategy – including social media – if they want to more effectively alter perceptions of the region in the international community. A challenge will be how they deal with increasing questions about Catalan aspirations for independence.

This highlights an interesting and unique aspect to sub-state public diplomacy and soft power, which is the attempt to achieve foreign policy goals through what Joseph Nye calls “attraction and persuasion.” Unlike traditional state PD, which is by definition focused on citizens in other sovereign nations, sub-states often have a need to also “attract and persuade” fellow countrymen outside their regional borders. This is especially true for autonomous regions, and of course even more so if they have designs on independence.

Yet many of the people I spoke to in Barcelona felt that outreach to the rest of Spain was, as one said to me, “a lost battle.”

This may be short-sighted, though. Tensions are high, but perhaps artificially so because of the economic crisis. Whatever solution Madrid and Barcelona come up with in the next few years will, presumably, require broad Spanish support. Catalonia, it is important to note, is according to some surveys the least popular region in Spain amongst other Spaniards. That will need to change in order to gain independence, or in the absence of secession, to create a climate favorable to their domestic and foreign affairs goals.

So while it is true that like other sub-states Catalan PD needs to focus on the broader international community, it is also undoubtedly the case that its fortunes lie to some degree in their ability to improve their image within Spain.

The coming months will be interesting. With the independence referendum still potentially two years away, there is perhaps time to negotiate a settlement short of secession, especially if the economy improves. At the same time, the rhetoric from both Barcelona and Madrid – in government and in the streets – could end up pushing both sides further apart. Of course one could argue, as many throughout Catalonia are these days, that the time for compromise has past.

Regardless of what happens, Catalan public diplomacy will play an important and intriguing role that will be fascinating for public diplomacy scholars to watch.