In the last few days much talk on has centered around Apple’s recent rejection of of an app called Endgame: Syria. The event has many lamenting Apple’s policies regarding violence in games, which insists that enemies in in software “cannot solely target a specific race, culture, a real government or corporation, or any other real entity.” But the game itself deserves some attention for how it uses mechanics to inform the user about a complicated issue: the real-world Syrian civil war.

Endgame: Syria rests somewhat uncomfortably in the mainstream conception of a “game”. The app places the player in the midst of the modern Syrian conflict, asking him or her make decisions for the rebels and guide them in their struggle to gain public support and inflict military damage upon the regime. Though it presents a complicated issue with a somewhat simple perspective, Endgame ia an interesting case study on how games address serious issues.

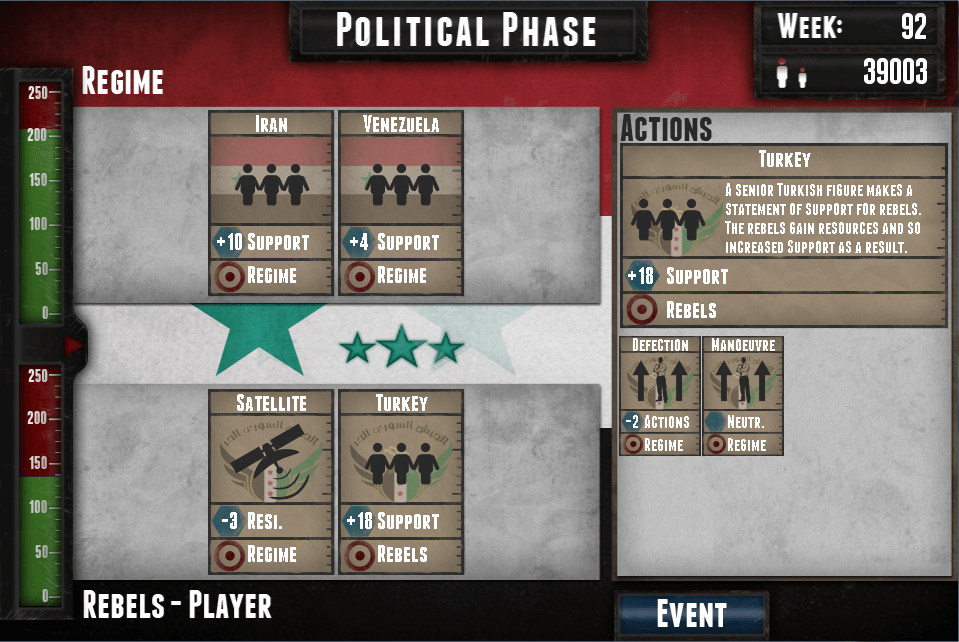

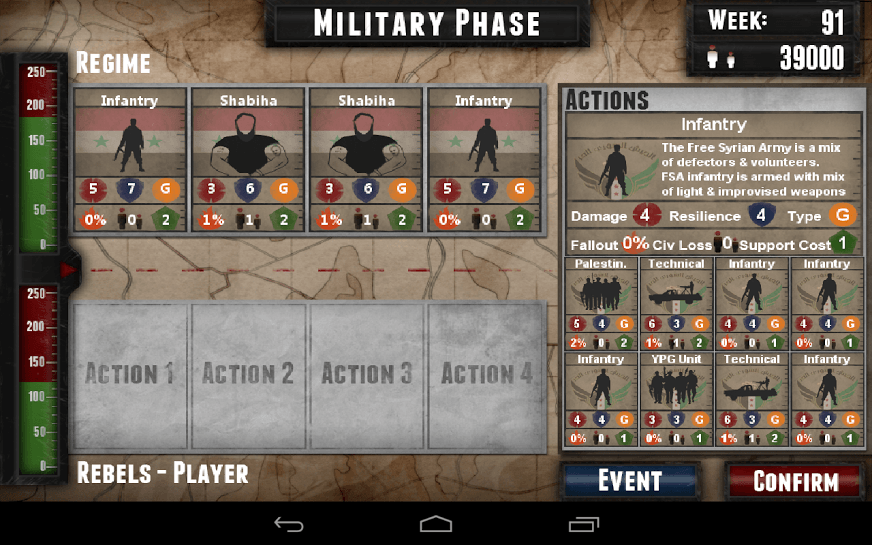

Endgame doesn’t seek to be a simulator – to comprehensively embody the complex interplay between politics, society, and war in Syria – but it does impart a basic understanding of the sort of challenges faced by the Syrian opposition. The player makes decisions during two “phases” of interaction: the Political stage, where the player strives to earn support from world leaders and enact various sanctions against the regime, and the Military stage, where rebels face off against powerful government forces.

Through gameplay, Endgame emphasizes the relationship between the military and political achievements of the Syrian rebels. Support from Qatar, or Saudi Arabia, or France in one phase directly translate into support during another, supplying the rebels with resources necessary to employ fighters. By placing the user in the position of making these important decisions, the game instructs the player on how vital these international supply lines are. Quite apart from being told that politics are important to the rebel cause, the player experiences the reality of resource scarcity firsthand.

As the game progresses, the regime steadily brings greater and more powerful forces to bear, including tanks, helicopters, and jets. The opposition must work with smaller forces, typically infantry. The player is presented with an attack from the regime and must choose which among his or her (mostly inadequate) forces will be selected to repel the opposing fighters. Using more powerful engines of destruction – captured tanks, often – results in a greater fighting chance but endangers the lives of civilians, which directly translates to a loss of foreign and domestic support. Placing the player in the shoes of an opposition leader making these decisions makes the combat realities of the Syrian rebels a little more understandable.

Endgame falls into a series of games which force the player to make difficult decisions and come to understand the perspective of real-life decision makers. Like Impact Game’s Peacemaker, which places the player in the role of either an Israeli or Palestinian leader in the peace process, Endgame revolves around making difficult choices where short-term decisions have long-term consequences regarding public approval and support. Sitting down in front of either of these games, the player can experience the challenges faced by a Syrian opposition commander, who has to balance waging a war with protecting civilians, or an Israeli politician, for whom ordering the evacuation of a settlement may amount to political suicide.

The experience is certainly an interesting way to encourage the average consumer, playing the game on an Android device or in a browser, to engage with the Syrian conflict that has claimed more than 60,000 lives to date.

Not everything about the game is perfect. Issue might be taken with Endgame: Syria’s somewhat simplified and smoothed take on a very messy war. The conflict is distilled down to monolithic representations of the regime and the rebels, leaving aside, for the most part, a wealth of sectarian and political subdivisions that exist on both sides. In having the player always responding to regime attacks, the rebels are presented as generally on the defensive, while real-life opposition forces have been on the offensive seizing land and making strategic gains across the country. Nowhere in the game is the player presented with the option of brutally executing captured regime soldiers, an act which has occurred after opposition victories and makes at least some of the rebels liable to be indicted for war crimes. For all its ambition to convey some of the challenges of a rebellion with legitimate grievances, the game runs into the classic problem of media surrounding conflict: how to tell a compelling story without wandering into the realm of propaganda?

Yet while the game may provide a simplified version of the regime and the rebels, it might be forgiven. Endgame: Syria provides a more serious take on war than most games on the market. Each of the player’s choices are connected with the inevitable death of civilians, driving home the reality that the war he or she is waging has real-world consequences for innocents. The game has multiple end states, including a peace deal that fully satisfies none of the parties, and a violent breakup of the nation into chaos. Most often, the player will simply lose, succumbing to Assad forces and leaving the dictator to rule over a broken country. Far from being a power fantasy in the vein of the world’s Call of Duty franchise, Endgame: Syria conveys an ambiguous, inglorious image of war… uncommon enough, in the games market today.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sa0GatiKnkU]

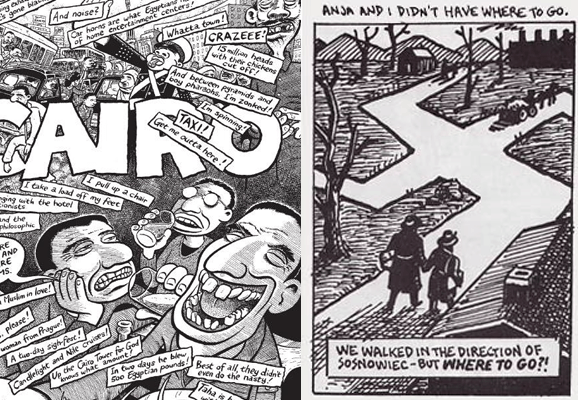

The game’s designer, Tomas Rawlings, is well aware of the challenges associated with engaging with a serious topic through a medium most often associated with frivolous entertainment. The trailer above was released alongside Endgame, as a sort of introductory primer for audiences unfamiliar with viewing games in a serious style. In the video, Rawlings pays homage to the work of Joe Sacco, whose exploration of the Palestinian conflict through a comic is an example of what Rawlings considers to be a “pioneer” of a addressing serious topics in non-traditional mediums. Sacco’s work addresses the themes of death, loss, and suffering in a medium that until recently was considered only appropriate for less serious fare. Rawlings, the creators a game focusing on rebellion and warfare, seeks to have Endgame exist within a similar space.

Today, comics appear to have made the leap into cultural acceptance in a way that games have yet to accomplish. Yet one can see that the two mediums have undergone similar journeys. One of the most famous serious comic series, Maus by Art Spiegelman, tells the story of the author’s father’s experience of the Halocaust. Although he eventually received the Pulitzer prize for his work, Spiegelman often worried that the story might be too complicated for comics to convey. Games, it seems, are beginning to experience a similar trial. “It is not the medium that is the issue,” says Rawlings, “but what you do with it.” Endgame: Syria is an honest look at a complicated issue, and is what we should hope to see in the medium of games.