Last week IPDGC and the U.S. Institute of Peace co-hosted a great conference, “Groundtruth: New Media, Technology, and the Syria Crisis,” that focused on the use of online videos by activists, new and traditional media, and policymakers. The event was the latest in the “Blogs and Bullets” series of research papers and conferences that have produced two major reports, and kicked off a new research project conducted by my GW colleague Marc Lynch, American University’s Deen Freelon, and myself.

There was much to chew on in the comments and observations of the various panelists, but I want to flag a few interesting nuggets concerning the role of social media in Syria – which Marc referred to as perhaps “the most social mediated protest in history” – and the complex intersection between new and old media.

First, a recurring theme from both activists and journalists involved the evolution of both social media and the public sphere in Syria as the regime’s hegemony wanes in the face of an ongoing civil war. NPR’s Deb Amos, who has been reporting on the Middle East for decades and the current Syrian crisis since it’s beginning, talked about how she has seen social media develop rapidly over the last year from something a few activists used to meet and share information, to something that is a more sophisticated tool for organizing, waging an information war with the regime, fundraising, and engaging with regional and world media.

Sometimes the online discussions via Facebook or YouTube comment threads and the like can turn viciously sectarian. After all, the pubic sphere, especially online, is not always known for its decorum. But even this can be seen as part of the maturation process as Syria moves from dictatorship to, perhaps, a more open society. For example, Rafif Jouejati of the Free Syria Foundation, pointed out that her organization has decided against censoring sectarian comments in favor of responding to them and thus creating a dialogue “so we educate against hate speech.”

Social media may be creating or strengthening the public sphere on multiple levels: within Syria and across the region. ABC’s Lara Setrakian called the “Arab digital vanguard” the “connective tissue throughout Arab Society.”

“Pan Arabism died a long time ago,” she said, “but it’s been resurrected online.”

There is, of course, a vast literature on the representative public sphere across several scholarly domains, highlighted by the work of Jurgen Habermas. Many have pointed out the complex role media play in fostering a functional and empowering socio-political conversation among the various layers in a society. On the one hand, media can create information baselines and be a conduit between elected officials and the public, among other functions. On the other, they can also misinform and misrepresent, be it because of their own latent biases (structural and ideological) and/or manipulation from sources, especially elites.

New media present these same challenges, as well as others. Fadl al Tarzi, from the Dubai News Group, whose organization has been monitoring social media across the Arab world, pointed out something that others have found in studying new media and politics in the U.S. and elsewhere: social media, more than traditional media, tends to include like-minded users. This is not often conducive to the (somewhat mythical) Enlightenment notion of an 18th Century Café/Salon style public sphere where ideas are contested on an equal plane with the best rising to prominence.

In Syria, one of the more interesting ways that new media are playing a role in shaping the information environment is in their use by traditional media, both within the region and across the globe. Several of the panelists, from activists to journalists, talked about how this has created an incentive for activists to create more credible media, rather than overt propaganda.

Rami Nakhla, of The Day After Project, discussed the way his organization has had to learn to adopt traditional Western news norms like balance to be taken seriously by mainstream media outlets interested in using their videos of regime violence, protests, etc.

The relationship between activists and traditional media can be a tricky one, though. The fact remains that it is still difficult to assess the credibility of many videos, many of which are of sketchy provenance and may not be depicting what they claim. Marc Lynch talked about the importance of being skeptical when a video claims thousands were at a protest, when in fact the tight focus of the camera may be obscuring that in fact only dozens were there. This is a phenomenon familiar to those who recall the exaggerated claims of thousands filling Baghdad’s Firdos Square when the Saddam statue fell on April 9, 2003, when in fact a couple of hundred were there.

Deb Amos raised another interesting challenge with traditional media coverage as the civil war continues and various rebel factions gain control of a growing segment of the country. In the early days of the conflict, outside media didn’t have much if any access to the fighting on the ground, making them more dependent on videos and other third-party sources of information. This is obviously not optimal for reporting and verification.

Now, however, as reporters are able to access places like Aleppo, a new challenge has emerged: Journalists may be over-reporting what they can see with their own eyes at the expense of important developments in less accessible parts of the country. “We have the same level of violence in Homs, but no coverage anymore because now journalists are able to get into Aleppo for a day” before going back across the border to safety.

This is a story familiar to any media scholar. Contrary to the claims of most prominent press critics (especially in U.S. politics), most press biases are not partisan but structural, the result of the routines of reporting and patterned and often latent norms that lead to certain stories, sources, and even places being covered at the exclusion of others.

What we’re seeing in Syria, according to Amos and others, is perhaps more credible, in the sense that it’s verifiable by journalist eye-witness accounts, yet at the same time less comprehensive, because it’s increasingly governed by a myopia of access. Journalists always have to contend with these problems, and Syria is no exception. This makes it increasingly important for audiences to critically assess a variety of news and information sources.

Finally, there is another type of structural bias we might be seeing in Syria coverage due to the prevalence of online videos in the news. Many panelists echoed the observations of others over the months in pointing out that the videos we see from Syria (and, before that, from other hot spots during the Arab Spring) often substitute for other types of reporting as stories within themselves. Schadi Semnani, of the Syria Conflict Monitor, for instance, commented that “lots of mainstream media use videos as their primary source rather than interviews with people behind them.”

There are many challenges associated with this, some of which I’ve discussed already. But another is this: videos tell one type of narrative, one that is highly episodic and typically vivid, rather than thematic or complex. They aren’t necessarily less informative, but they contain a different type of information, and therefore might be expected to influence audiences differently than, say, print reporting (online or off).

Research shows, for instance, that episodic narratives can have the effect of leading audiences to assume problems are caused by individuals rather than to look for more societal or structural causes, and, similarly, to look for solutions that are more punitive and focus on individuals. Put another way, an implication of this research is that episodic stories discourage support for diplomacy in favor of more bellicose responses.

There is also the question of what we learn from the videos and whether that helps us better understand the crisis they are depicting. Journalism’s principal job is, after all, to inform us in a way that helps us comprehend the world around us so that we can make sound judgments and assess our leaders’ policies. Videos tell us one kind of story. How journalists contextualize those videos will be a key variable in how people understand it.

If journalists rely overly on the videos to tell the story, one implication is that people might be more likely to simply understand the Syrian crisis through the prism of their own biases and predispositions. Research consistently shows that this is how most people process news they don’t know much about, and foreign affairs certainly fits that description for the vast majority of audiences around the world. But it also means that, within the region, sectarian predispositions might be a greater influence than the events and messages implicit and explicit in the videos and other social media coming out of Syria. This leads back to Fadl’s point about a collection of like-minded communities in the virtual public sphere self-selecting the media, and the messages, with which they already agree.

But it also places a greater value on traditional journalism, and the role of intrepid journalists to sift through an even greater array of information in making sense of complex crises like the one currently so tragically dividing Syria.

Darden and Mylonas recommend doing just the opposite, in two respects. First, the focus should be on building loyalty through cultural institutions, especially schools and religious organizations. “Coercive” institutions such as the police should come last. Second, external powers need to be willing to commit to a long-term, generational effort rather than looking for ways to extricate themselves as quickly as possible. Hence, they argue, nation-building comes before state-building, not vice versa.

Darden and Mylonas recommend doing just the opposite, in two respects. First, the focus should be on building loyalty through cultural institutions, especially schools and religious organizations. “Coercive” institutions such as the police should come last. Second, external powers need to be willing to commit to a long-term, generational effort rather than looking for ways to extricate themselves as quickly as possible. Hence, they argue, nation-building comes before state-building, not vice versa. Given this, the insurgent propaganda needs to be met head on and effectively. This is, principally, the government’s job rather than the media’s. Let’s say, hypothetically, that the insurgents are wrong and in fact the government is doing a good job, or at least an increasingly effective job, of improving services, security, and infrastructure. How will the people know? One important way would be through government spokespeople and other officials communicating this progress to the local population. But this is impossible if government spokespeople aren’t trained to be effective communicators, if the communication bureaucracy is not well-established, or if there are not proper channels of communication.

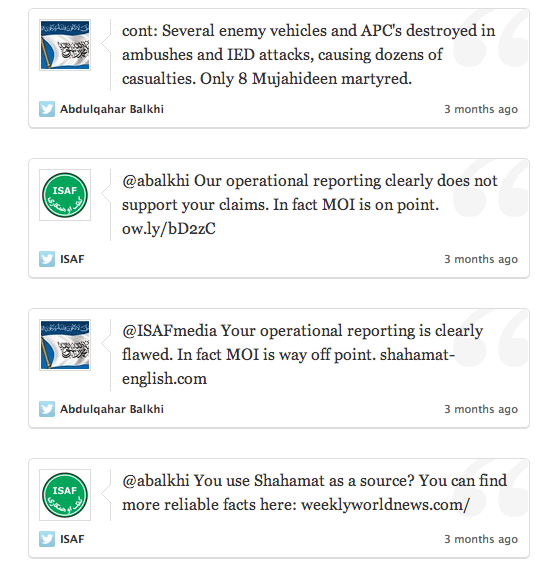

Given this, the insurgent propaganda needs to be met head on and effectively. This is, principally, the government’s job rather than the media’s. Let’s say, hypothetically, that the insurgents are wrong and in fact the government is doing a good job, or at least an increasingly effective job, of improving services, security, and infrastructure. How will the people know? One important way would be through government spokespeople and other officials communicating this progress to the local population. But this is impossible if government spokespeople aren’t trained to be effective communicators, if the communication bureaucracy is not well-established, or if there are not proper channels of communication. But another important determinant of government credibility can be a professional and independent media. I say “professional” because people in any society can spot amateurish journalism. Sensationalist and partisan or sectarian media are the prime offenders here, and they alienate audiences. (These concerns have always been the primary ones raised by government officials and journalists alike during the trainings I’ve led in Afghanistan and Iraq over the last few years.)

But another important determinant of government credibility can be a professional and independent media. I say “professional” because people in any society can spot amateurish journalism. Sensationalist and partisan or sectarian media are the prime offenders here, and they alienate audiences. (These concerns have always been the primary ones raised by government officials and journalists alike during the trainings I’ve led in Afghanistan and Iraq over the last few years.) To return to Darden and Mylonas, who emphasize schools as a cog in nation-building, a key long-term approach to strengthening local communication systems is getting beyond Beltway Bandit approaches that simply pay NGOs (and professors) lots of money (well, not to the professors…) to do short-term trainings. Instead, those resources should be put into helping universities (and secondary schools when appropriate) develop journalism and public affairs curricula and programs. Too often, even when these projects are funded it is only on the journalism side. But many of the same skills that make one a good journalist make one an effective spokesperson: Both are, at the end of the day, about communicating effectively to the people.

To return to Darden and Mylonas, who emphasize schools as a cog in nation-building, a key long-term approach to strengthening local communication systems is getting beyond Beltway Bandit approaches that simply pay NGOs (and professors) lots of money (well, not to the professors…) to do short-term trainings. Instead, those resources should be put into helping universities (and secondary schools when appropriate) develop journalism and public affairs curricula and programs. Too often, even when these projects are funded it is only on the journalism side. But many of the same skills that make one a good journalist make one an effective spokesperson: Both are, at the end of the day, about communicating effectively to the people.