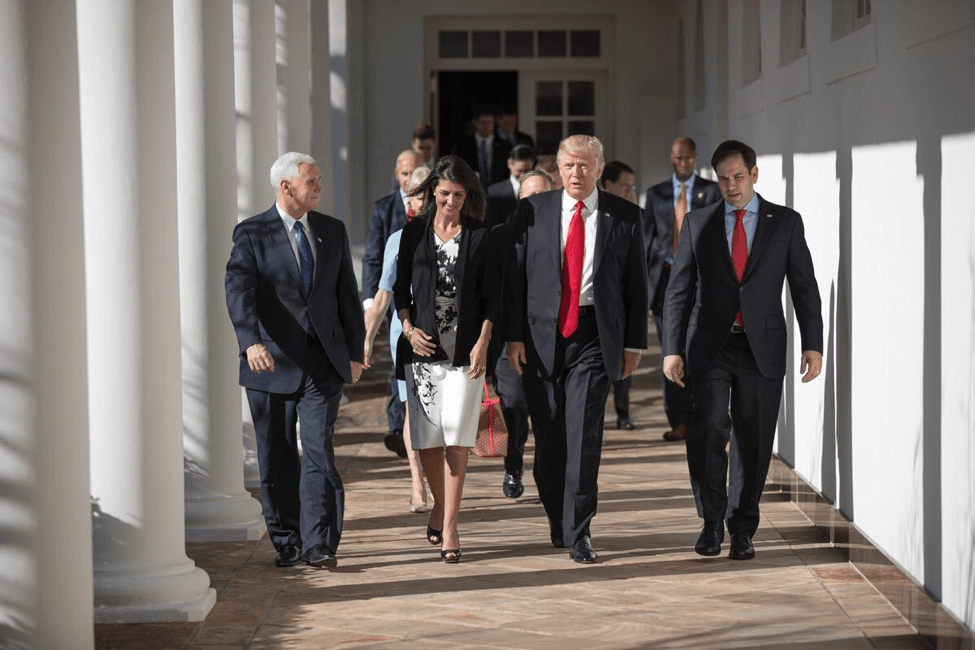

Both public affairs (PA) and public diplomacy (PD) officers have the privilege of representing a greater principal actor in whatever position they hold. This was the case with President Obama, having Samantha Powers one of his PD officers, and Josh Earnest as one of his PA officer; it is also the case with President Putin in Russia, and it is the case today under President Trump. However, the communication channels have changed for each of these actors in the new administration with the prominent role social media now plays, particularly Twitter, when speaking or tweeting with foreign and domestic publics. The constant use of the platform by President Trump has allowed him to create a sense of personal connection with reporters, constituents, and even international leaders, alluding to real-time and unfiltered content, but also weakening the role of the PA and PD officers who have a pervasive role of communicating policy. By analyzing the tweets from the current administration’s officials, President Trump (@POTUS), US Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley (@NikkiHaley), and Press Secretary Sean Spicer (@PressSec), each will give inside unto how the three should represent themselves and their policies on a social media platform such as Twitter.

The “I” in Team

President Trump has a unique role apart from the others because of the fact that he initiates the policies the other two advocate. For this reason, it is incredibly important for anyone in the role of the principal actor, as he is, to speak directly for himself. Out of the 238 tweets sent out in the first 70 days of the administration, 47 of which seem to be written by the president himself (using I, my, or me). In comparison, Spicer never used a pronoun in reference to himself, but Nikki Haley did. Seven of her 74 tweets in the same time period were about topics related to herself, from moving to New York to meetings she held. These personal pronouns are important for public diplomacy officers because of their ability to provide independent perspectives on the role they represent – this simple communication tool allows an audience to perceive a unique voice. Had Spicer or a public affairs officer used these pronouns, his primary audience of reporters would no longer use him as a source who is close to the principal actor they truly want information on.

Distance from the Principal

25 percent of the active user population on Twitter are journalists, therefore allowing Spicer the opportunity to speak with his most direct audience quickly. His credibility as a PA officer, comes from two things: proximity to the president, and ability to control the message of the White House. This represents the 129 tweets out of 225 total related directly to the president. The second aspect however, as mentioned above, can sometimes be interrupted when the principal actor, or President Trump in this case, tweets his own messages without putting a message through the office of the Press Secretary. Not including the messages using personal pronouns, the @POTUS account wrote 144 more in third person or spoke about the administration more broadly. On the other hand, Haley is also able to distance herself. Although she does represent the government which the president leads, as a principal officer, or head or a mission, she can refer to him less, as can other PD officers reference principal actors less, as seen in her two tweets about the president.

Personality

In addition to the importance, or lack, of showing personal use of the account, it is equally relevant to discuss mentioning personal topics on particular accounts. PD officers have the greatest ability of the three to show personality through their tweets because it allows them to portray to their followers knowledge of culture in their host country. Haley tweeted 25 times about topics such as her new favorite song, a television show she just watched, or her dog, Bentley. As she is representative of her own perceptions of the US actions, she is not as subservient as Spicer does to the President. Spicer does not have any tweets about personal matters. President Trump has one tweet about the Super Bowl, even signed DJT which occurs in seven other tweets – three of which were about the US generally, two about his role, and two about the media. While the principal actor may show personality in his tweets, as in the case of the Super Bowl, the 47 tweets mentioned above that speak directly about the president are a better use of this tactic. This allows any communications officers to direct audiences to the tweets for official opinions about important topics.

Foreign publics

While there are many other ways to analyze the tweets of leaders, from work related topics, family related, relaxed use of hashtags, etc., the last topic of importance to the PA, PD, and principal agent is communication with foreign leaders. As Twitter has a world-wide platform, it is impossible to contain messaging to just one part of the world. Therefore, a large part of tweets should be directed at foreign publics, but in different ways for each of the roles. From a PA standpoint, with the example of Spicer, it was appropriate for the small number of 19 tweets to discuss foreign affairs or meetings held with foreign leaders because his position is not to represent the foreign publics, but the principal. An even smaller number however, was that from President Trump. Only nine of his tweets related to issues of other countries. This may be due to the fact that he is yet to travel out of the country and is only taking meetings or calls in the US. Haley on the other hand had 33 percent of her tweets focused on foreign leaders and publics. This increase is due mostly to her face-to-face interaction with foreign diplomats every day. The real reason is the Haley’s mission is to represent the U.S. to foreign bodies, whereas Trump as part of his America first doctrine has focused mostly on domestic issues. However, this can also lead to problems when overlapping with personal content such as f the tweet from March 8, 2017, “On what will be an intense day on N. Korea and Syria, this was a sweet way to start the day…”Thinking Out Loud” by Ed Sheeran. Happy Wed!” This could be seen as inappropriate when discussing such a serious topic.

Changes to make

From each of these four factors, there are many tips for future PA and PD officers as well as their principal actors. Social media can spark revolutions, but it can also be misconstrued. For example, on February 9, 2017, Spicer spoke at a daily briefing when he received a question about why the president tweeted one topic, but not another to which he responded, “you’re equating me addressing the nation here and a tweet?” As a spokesperson for the principal, PA officers must simultaneously contain a message, while maintaining credibility. Not only were the tweets of his principal actor discredited, so was the method, and the message at large.

On another note, to spread a message on a world-wide scale as Twitter can, it is important to connect with the audience you want to see the message. In many cases, this is foreign publics, whether these actors like it or not. Because seventy-nine percent of Twitter accounts are held by users outside of the United States, and over 68 percent of world leaders hold accounts, it is important for each to follow and be followed by foreign leaders. President Obama was criticized for following only three foreign leaders – Nikki Haley is following Prime Minister Netanyahu aside from President Trump, Spicer is only following the president, and President Trump is not following any foreign leaders.