by Kate Mays

Looking at only the gender makeup of the Ugandan government, one could make the argument that Uganda is doing pretty well with gender equality. Women make up almost 35% of its current parliamentary members, and in 2011 the 9th Parliament elected its first female Speaker. Further, Uganda was ranked 28th in the 2012 World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report for political empowerment (compared to a rather shoddy 55th place showing for the US. Of course, gender parity in government is only one of many metrics to judge how equally genders are treated within society.) And the gender parity in Uganda’s government representation right now exists primarily because of a gender quota, which was included in the 1995 Constitution, and stipulates that each district must elect a female representative (to date, there are 112 total).

I am not going to delve into the pros and cons of Uganda’s gender quota – that discussion would be divergent and has been done effectively elsewhere – but it is an important premise on which to evaluate the Ugandan government’s approach to gender equality. Namely, one that embraces gender mainstreaming principles, which gained a lot of momentum after the 1995 Beijing UN Conference on Gender and Development, and continue to be practiced and implemented by some governments, the United Nations, the World Bank, and other international organizations.

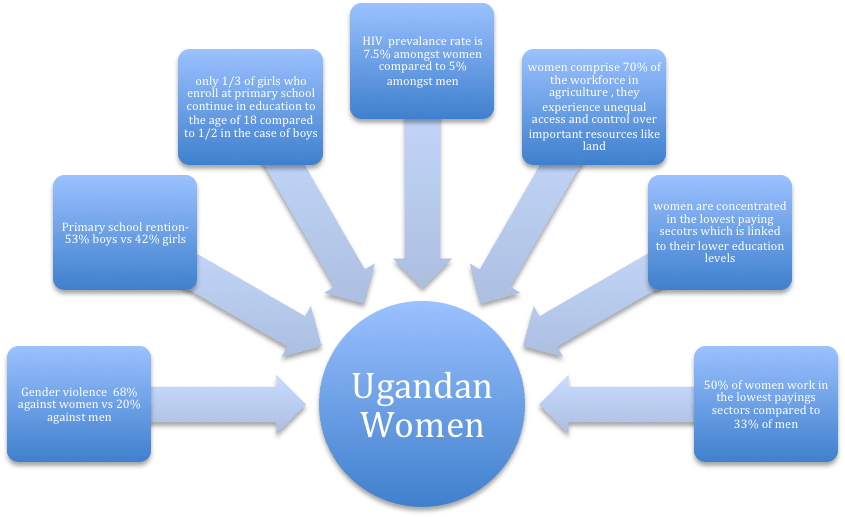

Uganda does not have a sterling history in terms of its treatment of women. In the economically dominant Bugandan culture, it is commonplace for women to kneel down before men as a respectful way of greeting them (men do not return the favor, neither to women nor other men). Patriarchy pervades Ugandan culture – this post from the WomanStats blog has a good description of the gender roles. In James Lull’s definition of culture, he emphasizes the “extreme repetitiveness of everyday behavior” as the foundation for culture: “Cultural redundancy produces and reproduces meanings which form the bases of coordinated social interaction.” While the act of a woman kneeling for a man in greeting might only seem like an odd, outdated cultural tradition, the societal manifestations of the patriarchal custom are more insidious. According to statistics from the Uganda Women’s Network, 60% of Ugandan women experience gender-based violence. While this has been the focus of some more-recent legislation, it will likely take more than a few laws to reverse the culture and improve on the kind of gender inequality highlighted in this figure.

However, even if the situation on the ground, culturally within the society, is still grim, embracing the language and principles of gender mainstreaming signals to the international community that the Ugandan government acknowledges that gender inequality is a problem that needs a solution, and shows that it is at least making strides to address it. (Uganda has a Ministry of Gender, Labour, and Social Development; it also crafted a National Gender Policy in 2007). For all of gender quotas’ potential deficiencies and possible exploitation, it is, I would argue, a step, and one that signals a commitment to being open to take further steps.

In his piece on Cosmopolitan Constructivism, Cesar Villanueva Rivas notes that “that the ways in which [countries’] identities and intentions are constructed abroad count.” Gender mainstreaming, at the very least, signals an intention, and helps to foster an environment of promoting women’s empowerment. As a result, countries like Sweden, Norway, and the US have shared knowledge and resources with Uganda, through direct engagement with the government in helping to craft gender policy, as well as through Ugandan universities and the numerous NGOs in the region.

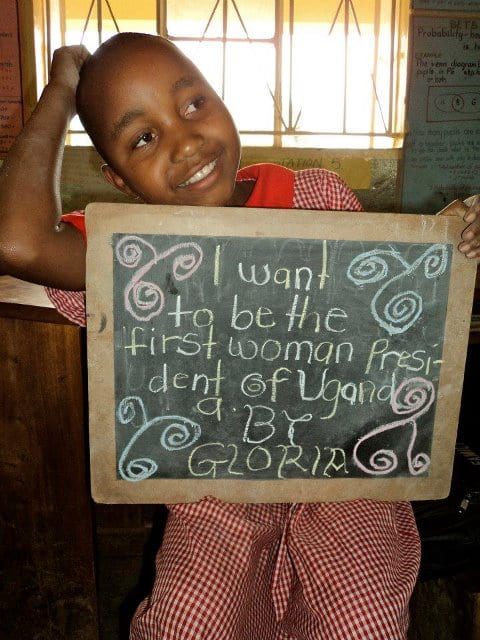

What does this mean for Uganda’s cultural diplomacy efforts around women? I would argue that there is a lot of potential for Uganda to stake a bigger global claim on some of the issues it has been working on domestically. Many countries in Africa have adopted gender quotas and are still struggling with similar obstacles to societal and cultural gender equality. Using the NGO infrastructure that already exists, Uganda could coordinate with women’s groups like the Pan-African Women’s Organisation and FEMNET (the African Women’s Development and Communication Network) to host a summit or forum on women in politics, with particular attention paid to leadership and advocacy. A similar program, the African Women Leaders Project, was held in 2008, but it was also run by outside organizations. Although a seemingly intangible detail, if such initiatives come from the African countries themselves it gives them a real power. Further, it would show that Uganda is not only open to accepting the “cosmopolitan” values of “tolerance, friendship, and respect,” but is also “internalizing” these values.

In his piece, Rivas cites Alexander Wendt, who identifies three “degrees” of internalization, the third being “legitimacy,” which is “the most developed of these actions pursued by states, since it emerges from the state’s principles and convictions.” Wendt uses the framework of “friends” and “allies” to differentiate the modes with which countries interact; “friends” is a longer-term relationship in which countries “join a process of common understanding and societal exchanges, step by step.” Within this framework also emerges the idea of a “Self” and an “Other.” Wendt marks progress by how a state can “identify with other’s expectations, relating them as part of themselves.” In the third degree of internalization, “Self is not self-interested but rather it is interested in the Other.” In this case, I would say the “Other” is both Ugandan women as well as countries abroad. Uganda should act for women’s empowerment in recognition of what their “expectations” are for being treated equally, and internalize that goal of equality as one of its own.

In his piece, Rivas cites Alexander Wendt, who identifies three “degrees” of internalization, the third being “legitimacy,” which is “the most developed of these actions pursued by states, since it emerges from the state’s principles and convictions.” Wendt uses the framework of “friends” and “allies” to differentiate the modes with which countries interact; “friends” is a longer-term relationship in which countries “join a process of common understanding and societal exchanges, step by step.” Within this framework also emerges the idea of a “Self” and an “Other.” Wendt marks progress by how a state can “identify with other’s expectations, relating them as part of themselves.” In the third degree of internalization, “Self is not self-interested but rather it is interested in the Other.” In this case, I would say the “Other” is both Ugandan women as well as countries abroad. Uganda should act for women’s empowerment in recognition of what their “expectations” are for being treated equally, and internalize that goal of equality as one of its own.

The disparity in how women are treated in Ugandan society and how they’re treated in the government’s official gender policies is problematic because it sends a mixed message to other countries. Tolerance, friendship, and respect have to start at home, in order to be credibly projected to the rest of the world. Just as gender quotas project a positive image, it is important for Uganda’s reputation abroad that Ugandan women’s lives continue to improve.

The above post is from Take Five’s Student Perspective series. Kate Mays is studying Cultural Diplomacy as Communication at the George Washington University, looking at themes such as youth, gender, health, climate, free press, and democracy, and writing on how these themes relate to cultural diplomacy and communication.