by Brad Gilligan

Last month, advocates of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights deployed thousands of supporters to the grounds outside the U.S. Supreme Court during oral arguments in two landmark cases. A Pew Research Center poll demonstrates the dominant frame being deployed by media to tell the story. “Growing Support for Gay Marriage: Changed Minds and Changing Demographics,” the headline reads.

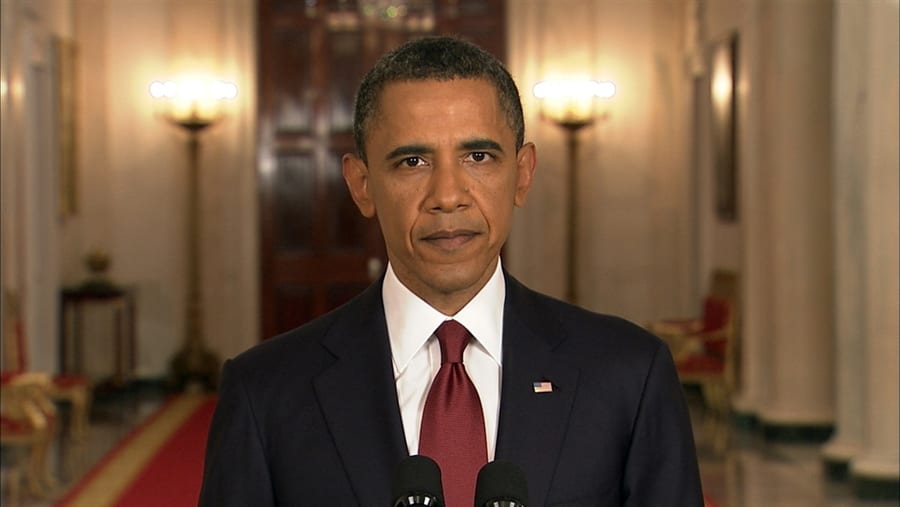

While the pro-equality campaign in the U.S. may represent a real sea change in our national public opinion, other countries’ perspectives vary by degrees. Under Hillary Clinton’s leadership, the State Department annually documented the status of LGBT people around the globe in its report on human rights practices. Memorably, Clinton said in a speech at the United Nations that “gay rights are human rights.” These remarks were coordinated with a memo from President Obama in the same week that detailed the first ever US government strategy to deal with human rights abuses against LGBT citizens abroad.

In parts of the world, perils faced by LGBT citizens are well known: In Uganda, the parliament proposed a bill which would make some homosexual acts a crime punishable by death. While in New York, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad infamously commented “we don’t have homosexuals like in your country.” And in Russia, parliament is considering a nationwide ban on ‘gay propaganda’ to minors—in the same year that international attention was drawn to members of the feminist, pro-LGBT, punk-rock collective Pussy Riot after they were jailed by the Putin government.

When the State Department promotes gay rights abroad, cultural diplomacy acts as one of the primary drivers of that agenda. Cynthia P. Schneider describes the relationship: “Public diplomacy consists of all a nation does to explain itself to the world, and cultural diplomacy—the use of creative expression and exchanges of ideas, information, and people to increase mutual understanding—supplies much of its content.” Through partnerships with regional and local civil society groups, the Department engages communities in dialogue about the value Americans ascribe to all people, no matter who that person is or whom that person loves.

Not to say that the U.S. does not receive its own share of criticism for its domestic LGBT policy: an interactive display from The Guardian documents the variability of gay rights, state by state. Until a 2003 Supreme Court ruling, sodomy laws remained on the books in 14 states. Today, others still prohibit adoptions by gay couples or permit dismissing workers on the basis of gender identification.

To focus on the theme of LGBT rights, and the practice of cultural diplomacy worldwide, I began with a small exercise in role reversal: How does one country (I selected Canada) work inside the U.S. to promote its foreign policy?

In 1995, a review of Canadian foreign policy granted culture new status, erecting it as a third pillar in the country’s diplomatic priorities, beside security and the economy. The report praises its culture as a potent force for the nation’s international reputation. “Our principles and values—our culture—are rooted in a commitment to tolerance; to democracy; to equality and to human rights”. Among the recommendations made in the document, it elevates the potential of mass media (e.g. television, film, and radio) in particular to reach audiences outside of Canada’s borders.

Like the BBC, the CBC (the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) operates as a public entity. The government approves and funds programming consistent with the mandate to, among other stipulations, focus on Canadian content. For instance, the broadcasting license for MTV Canada requires that a minimum of 68% of daytime and 71% of prime time programming be of Canadian origin. The network describes itself as offering a “distinctly Canadian interpretation of the MTV brand across multiple platforms,” in 171 territories around the world.

Like the BBC, the CBC (the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) operates as a public entity. The government approves and funds programming consistent with the mandate to, among other stipulations, focus on Canadian content. For instance, the broadcasting license for MTV Canada requires that a minimum of 68% of daytime and 71% of prime time programming be of Canadian origin. The network describes itself as offering a “distinctly Canadian interpretation of the MTV brand across multiple platforms,” in 171 territories around the world.

One such program, airing since 2009, is 1 girl 5 gays. The 30-minute talk show sees host Aliya-Jasmine Sovani asking 20 questions about love and sex to a rotating panel of gay men from the greater Toronto area. Toronto holds a reputation as a vibrant center of gay life in Ontario; Church Street, especially, has a rich cultural history and has been depicted before in popular media exported south of the border.

Logo TV, a US gay and lesbian-interest channel, picked up 1 girl 5 gays in 2010. The first season increased ratings in its time slot +55% compared to the network’s Q4 2010 average.

Pew’s poll, referenced earlier, found that roughly a third (32%) said their views changed because they know someone who is homosexual. Mass media may well be another variable at play, subbing for physical one-to-one contact. The show builds relationships on this principle, between the host and panelists (and the audience by proxy).

A rudimentary content analysis of episodes from 1 girl 5 gays’ first season begins to generate a map for how dialogue can be used to strategically shift opinion about LGBT rights. In any one episode, an average of five questions conjure pointed images of gay sexual experiences (“Do you have a gag reflex?”) while the remainder are interchangeable to hetero- or homosexual couples (“If your sex life was a colour, what colour would it be?). The majority have nothing to do with sex at all (“Whose autograph have you asked for?”).

A rudimentary content analysis of episodes from 1 girl 5 gays’ first season begins to generate a map for how dialogue can be used to strategically shift opinion about LGBT rights. In any one episode, an average of five questions conjure pointed images of gay sexual experiences (“Do you have a gag reflex?”) while the remainder are interchangeable to hetero- or homosexual couples (“If your sex life was a colour, what colour would it be?). The majority have nothing to do with sex at all (“Whose autograph have you asked for?”).

Especially notable, the show frequently inserts a question in the final segment looking inward at the program or at common LGBT experiences: “How do you feel gay men are represented on this show?” “Does the pride parade reinforce stereotypes?” “If there was a pill to make you straight, would you take it?”

Statistical wizard Nate Silver points out how demographics and population density are likely indicators of support for same-sex marriage. It would be overdrawn to say 1 girl 5 gays answers this problem intentionally by increasing the opportunities for exposure to discussion of LGBT experiences; but, as a byproduct of capitalism (i.e. the proliferation of broadcasting in the U.S. via for-profit cable TV), the amplification of Canadian commitment to tolerance aids the cause of LGBT rights in the U.S., and represents one instance of successful cultural diplomacy in action.

Brad Gilligan is a graduate student in the Media and Public Affairs program at the George Washington University.