By Saiansha Panangipalli, MA Global Communication, 2021

Projecting India as an Alternative to China

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, an association of the U.S., India, Australia and Japan, is committed to a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” Given that China concerns itself with geography and economic growth, its next-door neighbor and aspiring regional superpower, India can potentially be projected as an alternative to China. However, India has some way to go before its economic standing can match that of China. Further, to be a true alternative to China, India needs to position itself as less of a “regional bully” and more of a “benign hegemon” and reembrace the democratic values of freedom of expression and religion that it has traditionally stood for.

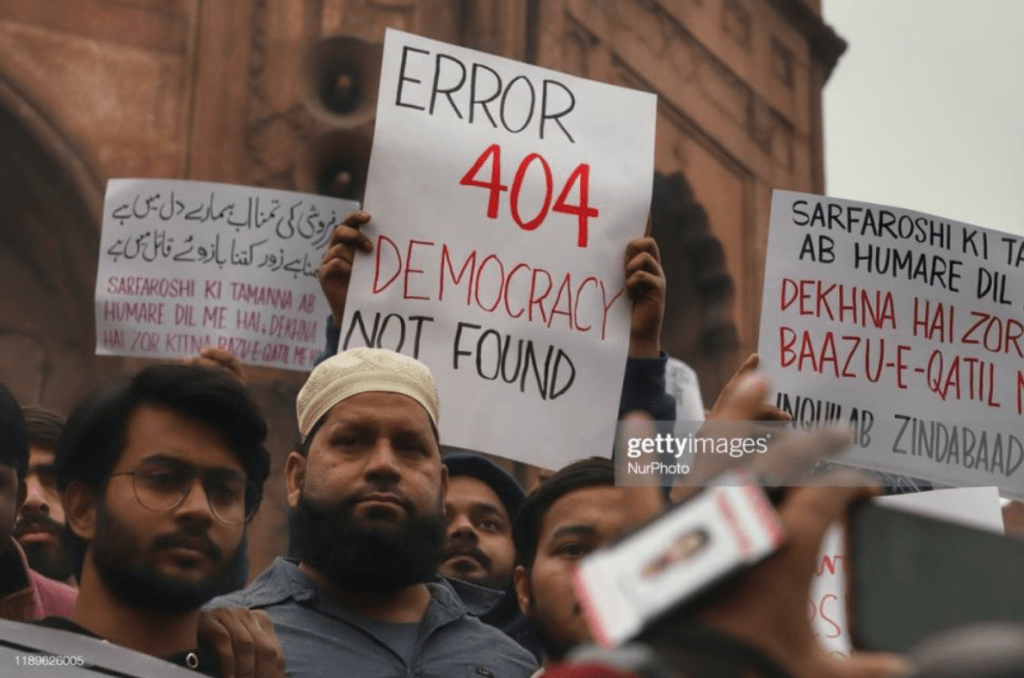

The U.S.-based Freedom House downgraded India’s status from “Free” to “Partly Free” in its annual report. Further, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom recommended Congress to mark India as a “Country of Particular Concern.” To project India as an alternative to China, the U.S. can tap into Indian master narratives and engage with Indian publics to renew India’s commitment to freedom of expression and religious harmony.

Indian Master Narratives

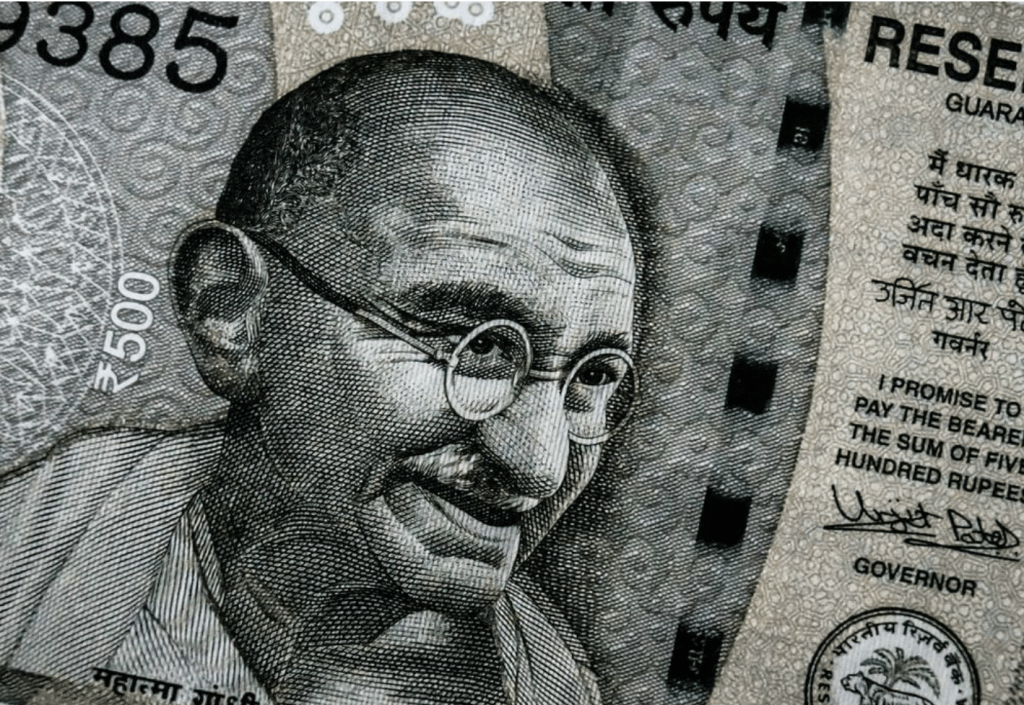

India has three key narratives that shape Indian public opinion: Mahatma Gandhi, the Partition of India in 1947, and the Hindutva ideology.

Mahatma Gandhi’s approach of non-violent civil disobedience in opposing British rule is a staple of Indian textbooks. It is difficult to talk about inter-religious harmony, unity among diversity, abolition of caste-system – narratives that form the master narrative about the modern history of India – without talking about Gandhi’s role in advocating for these tenets.

The Partition of India in 1947 is one of the bloodiest and most traumatic events in Indian history. Once the British decided to grant British India independence, it advocated the “Two Nations” theory: one nation for the Hindus and one for the Muslims. This proposition led to rising anti-Hindu and anti-Muslim sentiments, changing borders and steadily increasing cross-border movements, in turn resulting in the displacement and deaths of millions. The trauma and resentment from this event continues to spur and cause Hindu-Muslim communal tensions today.

Finally, Hindutva – or “Hinduness” – is the dominant form of Hindu nationalism. One of the most significant ways the Hindutva ideology has impacted contemporary politics is by supporting the building of Hindu monuments and reclaiming important sites. The Hindutva ideology entered into the mainstream with the landslide electoral success of the current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. Any critique against Hindu/Hindutva rhetoric is labeled by its proponents as “sickular” (secular), unpatriotic and anti-nationalist. Individuals who question Mr. Modi may even be called traitors and be arrested for sedition.

It is these master narratives – causing the Hindu-Muslim communal tensions and repression of freedom of expression – that the U.S. must counter to project India as a “benign” alternative to China.

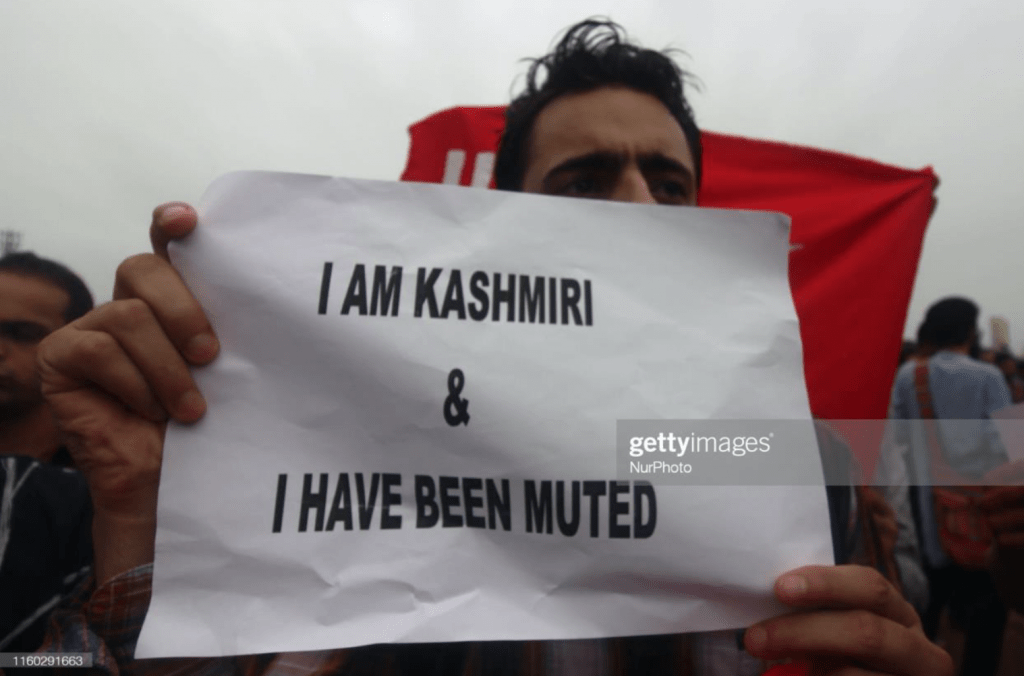

Freedom of Expression – Redefining What Is “Anti-Indian”

In 2020, India ranked #140 in the World Press Freedom Index because of the growing repression of journalists and media critiquing Mr. Modi. These journalists and their critiques are labeled as “anti-national.” The U.S. can disrupt the analogy by arguing that dissent or critique of Mr. Modi is not “anti-national” or unpatriotic. Rather, it is the suppression of dissent or critique that is anti-Indian, since colonizers used the same tool to suppress demands for independence and self-determination that are intrinsic to India’s identity.

Further, the U.S. can emphasize that freedom of expression and independence of the media make both the U.S. and India vibrant democracies that celebrate “unity in diversity.” Suppression of freedom of expression and media, however, weakens India’s democracy, eroding the unity in diversity that Mahatma Gandhi advocated.

Lastly, the U.S. can specify that it is possible to challenge critiques of Mr. Modi through the ideals that Mahatma Gandhi advocated – civil discourse and non-violence – rather than through the tool of the colonizers: repression and silencing.

Hindu vs Muslim – Decompressing History and Redefining the “Us” vs “Them”

The U.S. can ease communal tensions by “decompressing” Hindu nationalist narratives by outlining history beyond the traumatic Partition of India. It can argue that India’s history stretches beyond the two-centuries-long struggle for independence and colonial rule, and includes nearly two centuries of Mughal rule that made India one of the most prosperous lands of that time. The “us” vs “them” is not about Hindus vs Muslims – rather, it is about anyone who would challenge the unity in India’s diversity.

The colonizers propagated the “Two Nations” theory that led to the Partition of India. They introduced separate electorates for Muslims and Hindus, which Mahatma Gandhi opposed as he believed it would lead to inter-religious disharmony. The fear of being seen as succumbing to British rule caused Indian madrasas to reject introduction of rationalist subjects in their curricula – dividing Hindu-Muslim communities on the basis of education. Lastly, the colonizers used the “divide and rule” policy to prevent Hindus and Muslims from joining forces against the British.

Thus, the U.S. can emphasize that neither Hindus nor Muslims are the out-group. Rather, it was the British in the past and anyone who impedes Hindu-Muslim unity today that is the out-group and the “anti-Indian.” Hindu-Muslim brotherhood existed before colonialism and was only challenged by outside forces who did not have India’s best interests at heart. Hindu-Muslim brotherhood – referenced in a popular Hindi couplet – is what makes India such a vibrant democracy.

Deploying Counter-Narratives

The U.S. can deploy these narrative contestations by engaging with civil society – NGO’s, think tanks, women’s rights organizations, LGBT groups, legal experts and academicians – by organizing speaker series, educational exchanges and policy collaborations with the aim to persuade the Indian judiciary to take a stronger and more independent role in protecting the Constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression and independence of media.

The counter-narratives may not sway Hindu or Muslim extremists, but can be dispersed to educate and sensitize students and populations at risk of radicalization. The U.S. can again engage the civil society through lectures and exchanges to facilitate inter-religious partnerships in developing and disseminating textbooks, modernizing education in madrasas, and preventing radicalization as a tool to answer and solve systemic and practical problems.

For an in-depth analysis by the author on the subject, click here.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.