By Robin Terry

In February of this year, Philip Seib, who is the Director of the Center on Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California, wrote a blog post entitled “Climate Change, Terrorism, and Public Diplomacy” regarding a relatively unheard-of reality that public diplomacy must respond to. This reality was recognized by former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and is being made a top priority by her successor, Secretary John Kerry. This reality actually makes up three-quarters of our planet’s surface, and yet is one of the most fragile resources in many places in the world.

Water diplomacy is coming into its own as the world’s population mushrooms to 7 billion and counting. Kerry is already making climate change and a focus on oceans a major priority for his tenure at the US Department of State, disregarding climate change skeptics by declaring that the ocean system “is interdependent, and we toy with that at our peril.”

What makes public diplomacy important on this issue is that water is an indisputably essential and globally shared resource. Secretary Kerry recognizes that water diplomacy must be approached with delicacy to build bridges and maintain open communication (dialogue) to share and foster synergy, instead of becoming a battleground over threatened resources and an opportunity for imperialism. Seib writes, “Public diplomats representing nations such as the United States have long recognized the importance of water diplomacy. For years, the Peace Corps has worked with local communities around the world to ensure safe water supplies….” Global community projects centering around wells and water safety as well as water conservation practices in drought-stricken regions have proven to be effective tactics to bring about economic prosperity and an increased quality of life, and have also had an important public diplomacy impact by generating awareness and urgency, and highlighting cooperation. But what will bring about lasting change to the big picture? Will Kerry’s top-down approach to one of life’s most precious and fundamental resources deliver a vital answer?

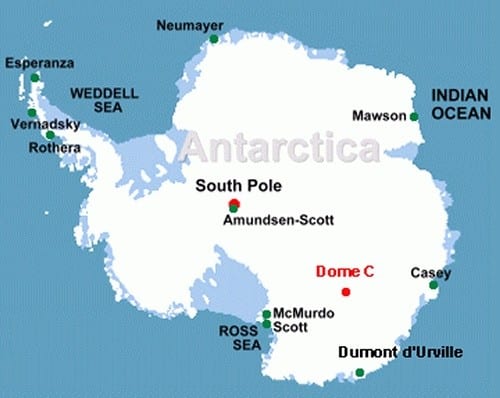

Secretary Kerry’s call to rally around the growing problem that is water security is coming out of the gate as a collaborative effort in a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, the Ross Sea. Secretary Kerry is aiming to create the largest marine protected area on Earth. These lofty ambitions, if successful, will create a foundation of conservation, collaboration, and global security in the frontier of water diplomacy. The biodiversity standing to be given sanctuary amounts to over 16,000 species including whales, penguins, and seals (fauna diplomacy, anyone?) over roughly 890,000 square miles.[1] Secretary Kerry is extending an olive branch of scientific opportunity and setting a conservation precedent that could provide capital for future public diplomacy goals. New Zealand is already on board in establishing the joint proposal and 23 other countries will announce their stance in July.

Water diplomacy caters to a very specific and absolutely requisite part of every human’s life. Therefore it is conceivable that a top-down emphasis on water diplomacy that encompasses major public diplomacy elements can have a significant effect. Other public diplomacy tactics such as educational or culinary diplomacy are collectives of bottom-up, separate attempts to address a big-picture issue. While this does not mean that these tactics are ineffective (I staunchly believe the opposite), it illustrates the diversity of approaches and the deliberate angle that such a fundamental resource, water, demands. Kerry appreciates how important this issue must be treated and is addressing the void that water diplomacy has played in the public diplomacy conversation as of late.

Water diplomacy caters to a very specific and absolutely requisite part of every human’s life. Therefore it is conceivable that a top-down emphasis on water diplomacy that encompasses major public diplomacy elements can have a significant effect. Other public diplomacy tactics such as educational or culinary diplomacy are collectives of bottom-up, separate attempts to address a big-picture issue. While this does not mean that these tactics are ineffective (I staunchly believe the opposite), it illustrates the diversity of approaches and the deliberate angle that such a fundamental resource, water, demands. Kerry appreciates how important this issue must be treated and is addressing the void that water diplomacy has played in the public diplomacy conversation as of late.

Water diplomacy encompasses national security, climate conservation, multilateral operations, and the (secret weapon) positive animal interest angle on a grand scale. By giving such a large-scale issue the stage and attention it deserves, will Kerry’s top-down approach prove more effective than the project-based approach used by other types of public diplomacy? Will public diplomacy associated with large-scale reform and change increasingly become the answer in our globalized society?