This post also appears on OpenCanada.org as a part of CIC’s ongoing series on Twitter and Diplomacy.

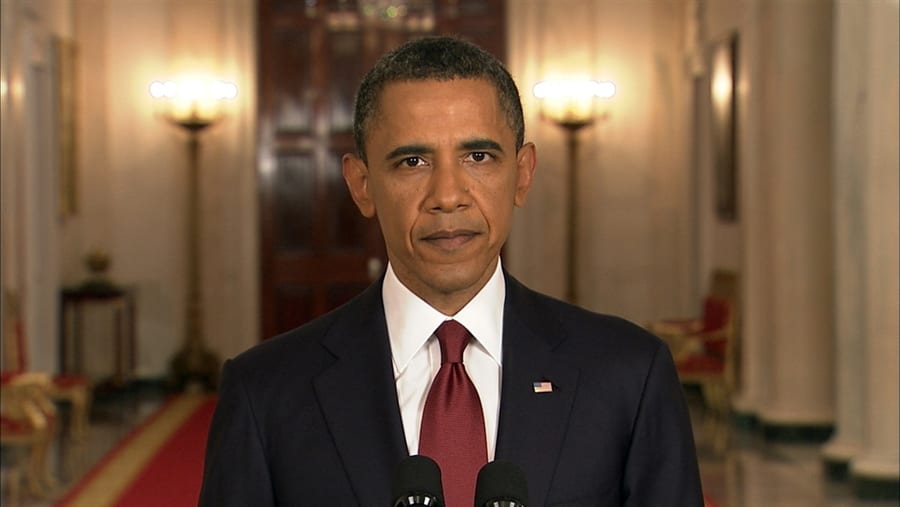

Earlier this week, Jackson Diehl’s column in the Washington Post argued that the Obama Administration’s early diplomatic approach to Syria, coupled with its failure to intervene militarily during the ongoing civil war, represented a “catastrophic mishandling” of the crisis. Diehl, like others who have blamed the Administration for not intervening, lay the blood of the more than 30,000 civilians killed in the conflict on the hands of Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Leaving aside the merits of the arguments for intervention (which, like Diehl’s, seem to take the ahistorical view that the U.S. can simply break up fights like Mike Tyson at a kindergarten recess), they point to the complexities of understanding the intersection of social media, diplomacy, and militarism in an era of Responsibility to Protect (R2P).

Ever since social media became a major part of the story of the Green Movement protests in Iran in 2009, many have argued that new media technologies not only have the power to help bring down dictators, as in Egypt last year, but also to pressure the international community to intervene and stop a regime’s violent oppression of its people. The dissemination of online videos depicting these abuses, spread via Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms, are supposed to not only rally citizens in those countries, but make it impossible for major powers in the West, especially, to turn a blind eye to the slaughter of thousands of innocent civilians.

As former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown said during those 2009 Iranian protests, “You cannot have Rwanda again because information would come out far more quickly about what is actually going on and the public opinion would grow to the point where action would need to be taken.”

Brown was widely ridiculed for his hyperbole. The Register’s Chris Williams wrote, “We’d like to see him try Twittering that to people in Sudan, or Northern Sri Lanka, or Somalia.” Today, one could add Bahrain and Syria to the list.

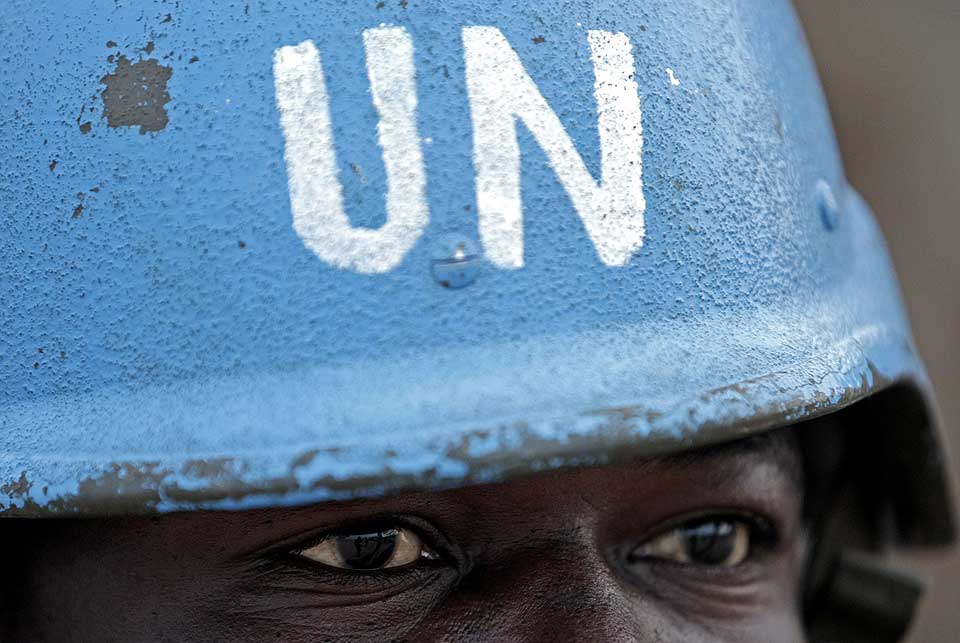

Yet Brown’s Rwanda allusion raises the issue of R2P and its relationship to social media-driven protests. At the 2005 United Nations World Summit, world leaders agreed in principle that the international community needs to be prepared to take military action to prevent a State from committing genocide or other crimes against humanity perpetrated against its people.

Yet Brown’s Rwanda allusion raises the issue of R2P and its relationship to social media-driven protests. At the 2005 United Nations World Summit, world leaders agreed in principle that the international community needs to be prepared to take military action to prevent a State from committing genocide or other crimes against humanity perpetrated against its people.

The Rwandan genocide weighed heavily on the Summit’s adoption of R2P as a guiding principle of international statecraft. The 1994 bloodletting, as well as the similar dawdling during the Balkan wars of the same decade, were seen as examples of diplomatic and military failures that led to the deaths of more than a million innocent people.

One of the reasons those genocides were allowed to happen, some felt, was because of the difficulty of documenting the atrocities in real time. There were, for example, very few journalists in Rwanda during the massacres, and according to former reporter and current scholar Allan Thompson, only one clandestine video of anyone actually being hacked to death was ever recorded. This is why Rwanda has been called a “Genocide without witnesses.” The assumption since then has been that had people seen the brutality in real time, world leaders in Paris, Washington, and elsewhere would have been pressured to intervene. As PM Brown’s comments 15 years later indicated, social media would provide those witnesses.

If this were true, it would dramatically reshape diplomacy. Some saw evidence of this in Egypt last year, when the Obama Administration initially responded to the protests in Tahrir Square tepidly – some said, too diplomatically – because Mubarak had been such a strong ally of the U.S. over the years. But those diplomatic ties snapped under pressure from Twitter and Facebook, according to this telling of events.

Shortly thereafter, the Administration invoked the spirit of R2P to join an international coalition to prevent Muammar Gaddafi from carrying through with his promise to massacre the residents of Benghazi through the implementation of a no-fly zone and other military actions.

In an era of social media, the story went, we would never again have a genocide without witnesses. Foreign governments in the West and elsewhere would not be able to withstand the public outcry that would come from seeing and reading first hand accounts of regime brutality. Diplomacy would be forever altered.

And yet… not so much.

Just taking the United States as an example (though we could easily choose others), well-documented and horrific regime violence has not prompted the Obama Administration to intervene in Bahrain or Syria, to name two examples.

Diehl and others see this as a “catastrophic” failure. Yet the reality is far more complicated, on many levels

Start with the fact that social media’s role in shaping international policy responses to Egypt and Libya are still poorly understood. My colleagues Henry Farrell, Deen Freelon, Marc Lynch and I recently released a report funded by the U.S. Institute of Peace that found social media’s role in the Arab Spring protests of 2011 were probably greatly exaggerated. At least when it came to Twitter and other mechanisms for sharing links to reports of violence and protests, social media didn’t appear to have as much of an impact within those countries or in the region as some expected. They did, however, generate a lot of discussion around the world. Hence, we argued, these social media appeared to behave as less of a rallying cry than a megaphone.

This raises the possibility, however, that all of that retweeting of horrific videos of regime violence could lead to pressure on governments to intervene. Deen, Marc, and I are currently investigating whether that has been the case in Syria. Our interviews with policymakers and others will hopefully shed light on how much impact new media played in shaping diplomatic and military responses to those earlier Arab Spring crises, as well.

But there are reasons to be skeptical that social media can lead governments to intervene when they wouldn’t have in the absence of these technologies. To begin with, there is the simple fact that the U.S. hasn’t intervened in Syria militarily, much to the dismay of Diehl and others. Coupled with its relative silence during the Bahrain protests, this suggests an explanation familiar to international relations scholars and observers: States make foreign policy decisions based on their perceived interests, and these are much less susceptible to public pressure than domestic policy decisions. In the U.S. this is especially the case, in part because Americans don’t know (or care) much about foreign affairs, and press coverage of the topic is correspondingly, and vanishingly, scant, superficial, and episodic. (In general; clearly there are great foreign correspondents doing work that deserves greater exposure than their parent organizations will provide them.)

Ideally, States also make decisions based not on mismatched historical analogies (“Look! Hitler!” or “It’s just like Libya! Intervene!” or “No, wait, it’s just like Iraq! Run for your life!”), but rather based on the specifics of the case at hand. (In fact, however, research shows that policymakers frequently employ convenient historical examples to justify policy decisions they’ve already come to.) One question to ask would be, will intervention actually accomplish the goal at hand? Another might be, at what cost? And a third would be, how do we do know?

So where does that leave us in terms of understanding the intersection of social media, diplomacy, and intervention?

First, social media can create global witnesses to regime violence and genocide. If world leaders are going to take R2P seriously, then this could be an important tool in making that doctrine more than empty words. If nothing else, this witnessing can be crucial to accountability and justice in, say, war crimes trials, but also in not letting leaders off the hook for craven failures to act.

Second, diplomacy and policymaking can be greatly enhanced by social media. For instance, the growing sophistication of crowdsourcing verification of online videos and other means of what Patrick Meier calls “information forensics” can help separate truth from propaganda. It can also be used as a tool for diplomats to pressure regimes, by brandishing documentary evidence of their abuses, or to pressure others in the international community to join coalitions to stop those abuses.

Third, social media can aid diplomats in their effort to connect with citizens in other countries. We saw this in the creative and aggressive way that Amb. Robert Ford and the U.S. Embassy staff in Syria used social media to document abuses by the Assad regime before Ford was forced to leave the country. We also saw it in the way that the U.S. Embassy in Bahrain used their Facebook wall to host and engage in spirited conversations with people from different sides of that conflict. This is an important way in which social media are helping to more fully integrate public diplomacy into traditional diplomacy.

Finally, however, we are left with the limits of social media’s impact on diplomacy and policymaking. In the Syrian crisis, for instance, we still have problems with verification and propaganda in the online public sphere. And traditional questions about national interests and, especially, feasibility undercut interventionist sloganeering.

What that means is that social media have probably not fundamentally altered the foreign policy decision making process of world leaders to force intervention, but rather merely contributed to the range of data diplomats have at their disposal. This, however, is not always a bad thing, since intervention is one of those things that’s easier said than done. In fact, it could simply mean that effective diplomacy is all the more important.