Public diplomacy is about communicating—including lessons learned. So here are a few lessons I have learned from serving in high level positions in government:

1. The first is about idealism vs. realism—how to blend them. You come into government very idealistic and you go home very realistic. But the truth is that the first and last lesson I keep learning is about BLENDING BOTH—meaning that you have to blend ideals and aspirations with what is doable.

That’s hard. As an old friend of mine, Max Kampelman once said, there is what we ARE and what we OUGHT TO BE. Both matter. Resources are tight in the world, but the possibilities of what we can and want to do are endless. So the trick is how to balance both.

At as Under Secretary at the State Department, I had to balance the need to THINK BIG and the painful reminder each day that sometimes what we had to work with was SMALL. I had to balance, at times, the creative urge to deliver real value overseas to local citizens, and the restrictions of the State Department, the legal and administrative requirements, and the accountability to Congress.

So the first lesson is: Strive to accommodate creativity and realism and not see them as a trade off. You can do BOTH. But not always simultaneously and not always to the full satisfaction of everyone. But if you are open, accessible, clear, and honest—everyone is better off and better understands that mid point between the sky and the floor and that often we live somewhere in between.

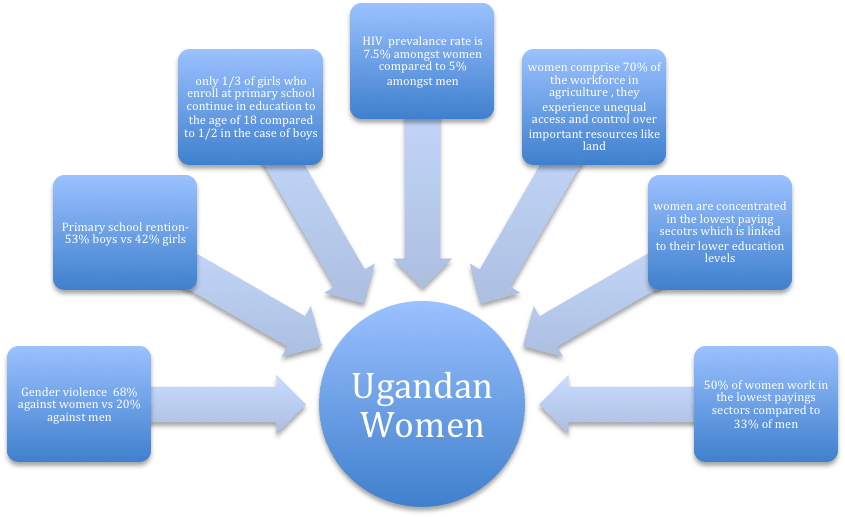

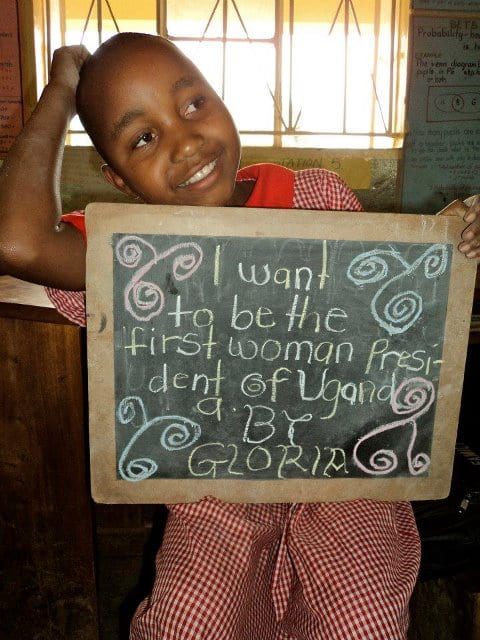

2. The second lesson I learned, not only from State, but from 35 years of working on global issues is that we cannot fix others if we don’t fix ourselves. We can’t tell governments to stay open and then shut our own down. We have to be as open and transparent as we want others to be. We can’t tell other countries, for example, to put women at the top of their governments if we have never done that. We can’t want things for others more than they want them for themselves.

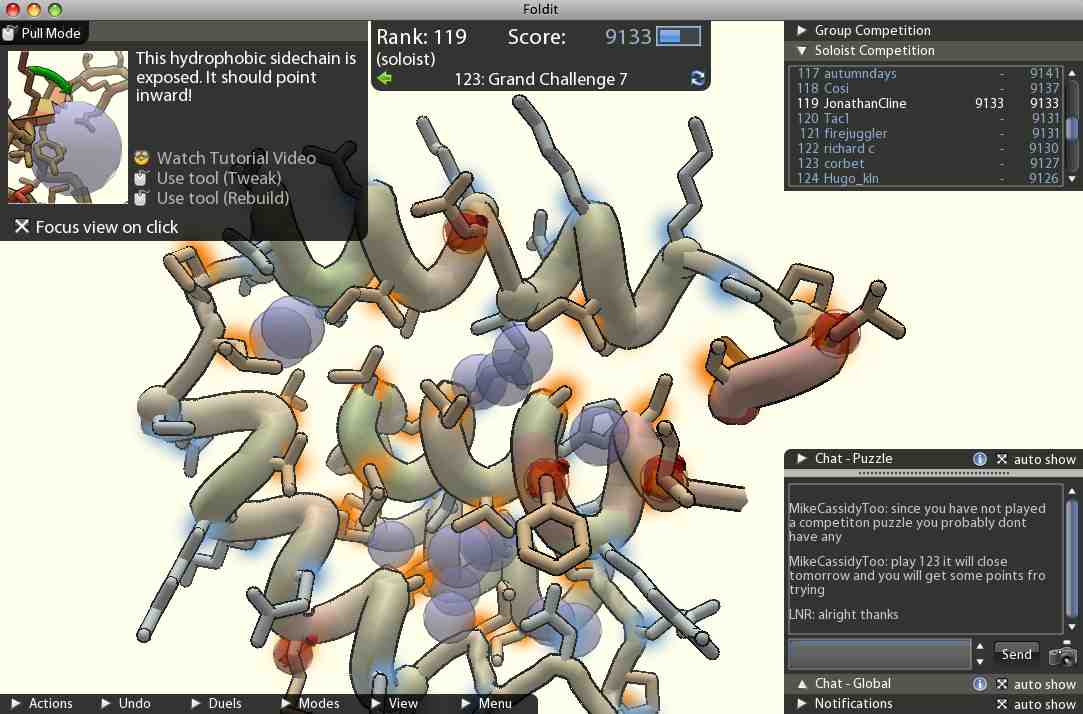

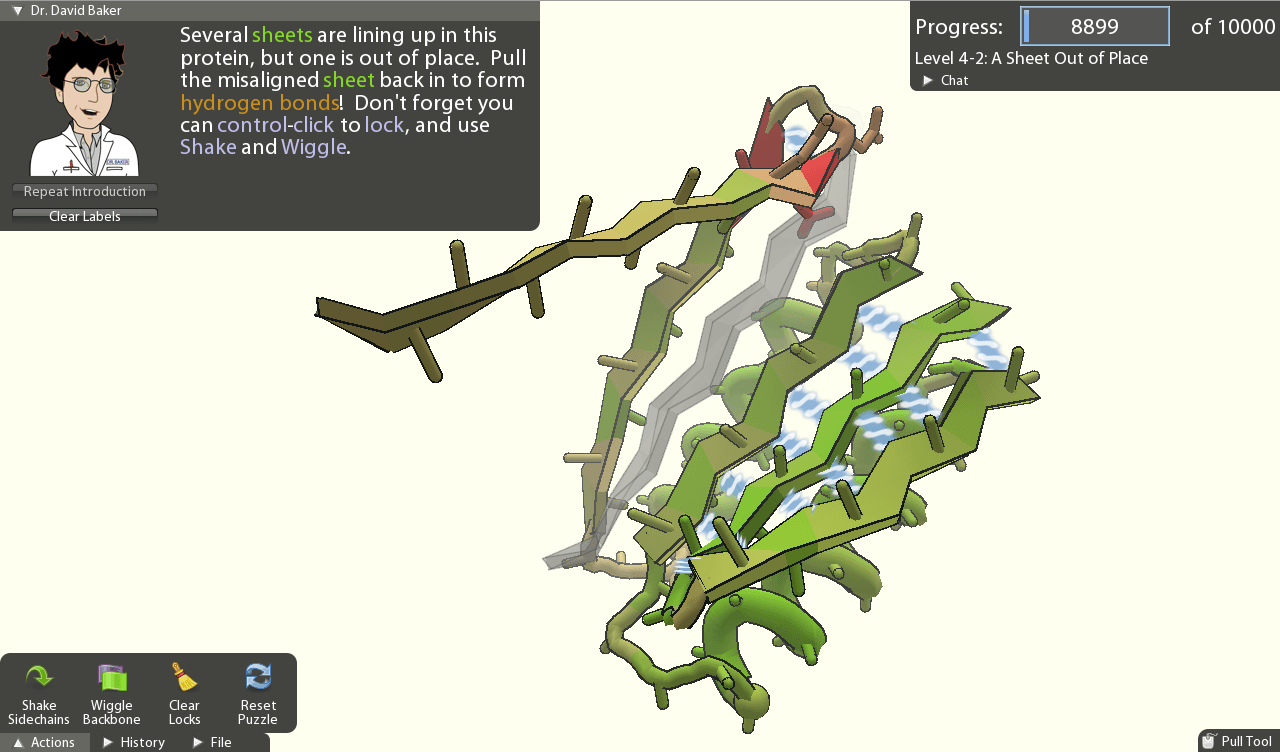

3. The third lesson I learned is that individuals matter; however, the best way to empower individuals is through teams – but TEAM WORK is hard. It is easy to lock yourself into a room and come up with a brilliant idea all on your own; it is harder to execute that idea or test its proposition without others.

Nobody today goes to space alone. We go to the International Space Station even with countries we can’t agree with on Earth. Just as we would not want to be out in the galaxy all alone, we don’t want to save the world all by ourselves. And the world is listening and watching what we do and participating in what we do… so we have to communicate with each other and with those outside our bubble and deal with different fragmented audiences while not losing sight of the big picture.

4. The last lesson I learned is that to LEAD, you also have to FOLLOW, and listen carefully to those journeying with you or behind you. And that how as leaders in an organization we are role models and we need to be as diverse in our skill sets, knowledge and experiences as possible. We have to set good professional and personal standards. In government, I found the near obsession with the crisis of the day, with the flooded inbox, the fires to put out now, and not pay attention to the brief flicker of a coming flame. We get so caught up in the work of the day, that yesterday is so long ago, and tomorrow not even possible to ponder. So I try to be thoughtful about lessons learned from the past, and to be learned in the future.