By Richard Outzen, retired U.S. army officer

Experts have come to recognize that international competition in the Internet era includes a continuous struggle to define conflicts and outcomes through messaging on social and mass media. When actors define a situation by publishing messages – data, images, words for framing and narrative – they are competing to shape interpretations among target audiences. This battle of narratives, or contestation, is not primarily a search for truth or reporting of fact; it is the interplay of stylized stories that incorporate facts and interpretations to persuade for political purposes. Armies, diplomats, and corporations help states determine outcomes in international relations, but so, too, do narratives.

Developments in Libya during 2020 exemplify how narrative contestation can complement or eclipse other tools of statecraft during interstate conflicts. At the beginning of 2020 one side in Libya – Khalifa Hafter’s LNA, backed by France, the United Arab Emirates, and Russian mercenaries – sought to convince world leaders that only the fall of Tripoli could bring stability. The other side – The Government of National Accord (GNA), backed by Turkey and recognized by the United Nations – sought to defeat Hafter and to convince Libyans and world leaders that only a compromise settlement could end the war.

Turkish intervention in Spring 2020 led to Hafter’s defeat, a new ceasefire, and calls to resume negotiations. The LNA and its allies unleashed a blistering critique of Turkish actions, arguing that Turkey’s role was illegitimate and illegal, and the Turks should have no role in Libya’s future. The stakes were high: if major international players saw Turkey and the GNA as theproblem and Hafter as the solution, their military success would be irrelevant. What happened instead was military de-escalation, a UN-brokered agreement, elections, and a unity government.

Formation of the Narratives

France, supported by Egypt and the Gulf, attacked Ankara’s role in Libya as a “dangerous game,” a tragedy for which Turkey bore “historic and criminal responsibility,” and as a risky intervention likely to backfire. Egypt, Greece, and the Gulf monarchies (minus Qatar) issued a Cairo Declaration calling for Libyan unification on Hafter’s terms, with departure of Turkish and Turkish-supported forces. Turkish President Erdogan was portrayed as irresponsible, dangerous, and extremist.

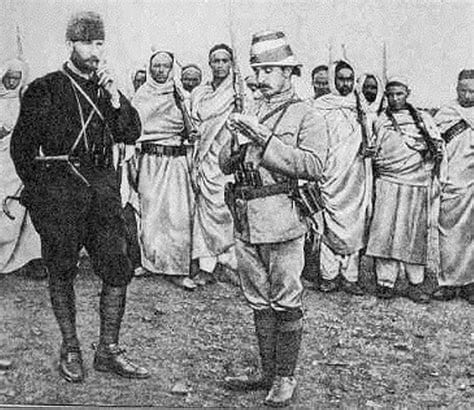

Ankara’s counternarrative relied on three key factors: assertion of Turkey’s historical ties to Libya, UN-conferred legitimacy of the GNA, and portraying Hafter and his backers the real aggressors. Image 2 below shows an image popular in Turkey and Tripoli – Ataturk in Tripolitania during the 1912 war against Italy.

Projection of the Narratives

The U.S. Department of Defense Africa Center’s study of messaging by both sides in the Libyan Civil War noted that foreign disinformation campaigns created a “fog of disinformation” around the fighting. The LNA relied on a Russian-supported disinformation campaign designed to obscure, confuse, and overwhelm Libyan digital spaces. Saudi and Emirati networks of fake Twitter accounts began lionizing Hafter in 2019. Egyptian firms and the Russian Wagner group employed digital experts familiar with Libya to sow disinformation resonant with local audiences.

GNA backers, notably Turkey and Qatar, relied on traditional state-backed television and media. Two factors made this effective. First, given mounting empirical evidence linking Hafter to mass killings and other abuses, the GNA/Turkey felt less need to manufacture outrage. Second, local Libyan influencers – individuals, academics, and militia affiliates – already provided rebuttal of the more outlandish pro-Hafter, anti-GNA/anti-Turkish messaging. Turkey also benefited from the impressive visuals associated with drone strikes against Hafter’s forces.

Turkey and GNA published images of effective drone attacks on LNA forces to bolster the counter-narrative of professional, precise defensive operations.

Reception of the Narratives

Because key international players ignored the characterizations of Turkey as the real villain in Libya, the United States and Russia, Italy and the United Kingdom and Germany continued to treat Turkey as a partner in resolving the conflict, and dismissed the Cairo Declaration. By August, the “rogue Turkey” narrative had petered out. Washington-based think tanks panned the Cairo Declaration and attempts to bypass the UN, while other observers ridiculed Macron’s statements of execration against Turkey.

Miskimmon, Roselle and O’Loughlin provide a useful framework for analyzing narrative contestation. For a narrative to dominate in a contested information environment, it must outperform rival narratives in formation, projection, and reception. The chart below applies the framework to narrative contestation in Libya in 2020.

| Aspect of Narrative Contestation | French Narrative | Turkish Counter-Narrative |

| Formation/Content | Turkey portrayed as aggressive, irresponsible, and extremist; no legitimate role in the future of Libya. | Turks focused on historical ties with Libya, on UN recognition of GNA government, and on LNA as actual aggressor/war crimes perpetrator. |

| Projection | Russian-supported disinformation campaign, supported by UAE/Egypt, plus public statements from Cairo/Paris. | Turkey/GNA relied on traditional state media plus local non-government influencers. Utilized string of impressive military victories, enabled by Turkish drones.\ |

Reception | Failed to persuade significant portion of GNA supporters in Libya or international actors outside. | Libyan and European social influencers (e.g. Wolfram Lacher, Emadeddin Bali) and European leaders maintained critical, but balanced approach toward Turkey and the GNA. |

Verdict

The narrative to anathematize the GNA and Turkish intervention failed. A friend of Turkey became interim head of government, while Hafter was marginalized, while key international actors moved toward a compromise settlement that did not exclude Turkey. The key takeaway from Libya’s 2020 battle of narratives is that sometimes “less is more” – a torrent of disinformation and malediction won’t convince skeptical observers when your armies are losing territory and moral high ground at the same time.

For an in-depth analysis of Turkish narratives and recommendations for U.S. public diplomacy, Click Here.

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. They do not express the views of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

Main photo: Macron, the Russian Wagner Group, and other Hafter patrons constructed a narrative based on the extremism of the GNA and Turkey.

This analysis is a great example of how diplomacy can’t save bad policy. Even though state-run television may be considered archaic to us Americans, it also presents a more streamlined, controlled channel that can reach the right audiences, ultimately having a more impactful effect. Additionally, as we’re learning in class, a visual is worth a 1,000 words. I appreciate that your post challenges the widely accepted notion that social media diplomacy is the new normal, because it doesn’t have to be.

This is an interesting example of why we need to consume news from multiple sources. The casual reader, especially on social media, may assume that the primary goal of news articles is factual reporting. But this demonstrates how it’s really a competition for influence. Sometimes the pictures are the news.

On point analysis!

News needs to be factual with words and visual reporting. I admit that occasionally I might have been influenced by misleading points of view. Diplomacy is a tool which should be used and impacted with facts and not via opinionated,influencing news.

.

It appears that the impact of the manufactured outrage was not felt strongly in this instance. But in the absence of a legitimate, well-documented and compelling counter-narrative, the manipulation of public opinion can go unchecked.

Being able to see the multifaceted reality of conflict outside the confines of partisan viewpoints is incredibly important. This articles outlines some of the flaws in portraying complex issues in such ways.

In an age where a lot of discourse revolves around the role of social media in disseminating disinformation, it’s refreshing to see that responsible and conventional messaging can still “win,” so to speak, in the face of deliberately falsified narratives.

Insightful. Would it cloud the issue too much to address how each actor’s narrative may have been directed at or perceived by internal/domestic audiences? In the current information environment there is no way to insulate your own populace from any messaging efforts abroad. Not meant as criticism but would appreciate hearing your view.

It is unfortunate that a) relatively few readers in the U.S. consume news from multiple sources and thus can’t compare/contrast the very different framing involved with such competitive narratives and outlets. Some of this is a matter of time/effort, and some from a general disinterest among (some) Americans regarding foreign affairs. This article highlights how such comparative reading can help weed out sensationalist and deceptive narrative elements. Critical reading is a must.

Interesting analysis of this modern day narrative battle between a traditional versus digital/social media approach. While Turkey succeeded with a more traditional, fact-based strategy, in this case the ultimate decision-making target audiences (heads of state, senior international political players) were likely more receptive to this approach. In the future, however, as small but highly activist agitators begin to wield greater influence over public opinion through social media and other digital avenues, future battles of this kind may reach very different outcomes.

This is certainly a timely discussion. Manipulated media dissemination may not be a new phenomenon, but the many developing media channels must continually create new challenges, as well as opportunities. It is encouraging that State-sponsored and well-funded media campaigns can be successfully countered, at least in this case where the outcome is positive. Perhaps these campaigns are now a fixture in the planning and execution of future interventions.

Interesting discussion on what really is information warfare and the reasoning how some information is better absorbed and understood than other forms. We saw similar things in the Arab Spring about a decade ago. There the biggest factor was age and generational thinking and how one received or moved information. The older generational set in the Government had not yet become accustomed to the internet and the social media platforms, how they worked and who they effected. The youth moved large amounts of information in to and out of Egypt via social media and had players in Europe providing services that the Govt couldn’t touch quickly, thus bypassing Govt sensors to what was going on at the highest levels of the Governments involved. In the discussion above, it seems that the means and who received what information did make a difference, what I did not see was how the information effected the actions of the populace, if they were the targets of the information or was some other aspect like Government decision makers and their actions? Additionally, having outside influencers (French vs Turkey) providing and forcing the information could also cause miss targeting in how the perceptions in country are received via nuances in translations and cultural issues / barriers.

The use of Miskimmon et. al’s narrative contestation chart was extremely helpful in demonstrating why and how these narratives either failed or succeeded. As many others in the comments have stated, some of the most interesting takeaways revolve around the role and impact of alternative channels of media, such as social media, on the adoption of narratives. In other cases, such as during the Arab Spring, social media was amplified to demonstrate that the state-run media narratives were inconsistent with what was actually occurring on the ground, while, here, it is being used to the opposite effect – to project false accounts of reality.

The role of more authoritarian governments with tighter control over media dissemination within a country in countering disinformation is also incredibly interesting. It would be fascinating to further explore the tension between media environments, political systems, and disinformation.

You managed to put a lot of information into few words and the visuals highly complimented the writing. It is fascinating to see how a “disinformation fog” can eventually break and how social media can both work for and against your narrative.

This topic was so complex but you managed to The table and the images helped to understand what could be a really difficult topic. Excellent choices. I have to say, the takeaway for the verdict is so interesting: “a torrent of disinformation and malediction won’t convince skeptical observers when your armies are losing territory and moral high ground at the same time.” No doubt, you proved your point in this context. I would like to see how that is applicable in other battles of narratives; and if not, see what variables change the verdict.

I really appreciate your chart of the aspects of narrative contestation, really nice way to sum up your argument. I also found the idea of the “fog of disinformation” a really interesting way to describe how narratives from both sides were acting against each other.

Great use of the narrative contestation chart. This is one of the few cases where traditional state media was more effective than using online tactics to project a certain narrative. I wonder if that’s because these audiences were more receptive to traditional media or the French narrative was simply too weak to hold.

Richard, I do not have an understanding of the events you have described, but your description of the battle of the narratives was clear, focused and informative. I would love to learn more about what other specific messaging Turkey used to advance its narratives. What appealed to the Libyan audiences? What were the hits and misses? Did Turkey ever directly challenge France and other gulf countries (except Qatar)?

Great analysis Richard! I think another useful counter narrative that Turkey could have used (I’m not sure if they did or not) to counter the French narrative of Turkey playing a “dangerous game” in Libya would be to point out the French-led NATO bombing of Libya in 2011. Turkey could use the inherent hypocrisy of the NATO bombing helping to create the environment that forced Turkey to intervene in the first place. But I’m not sure how effective this would have been since Turkey is a member of NATO.