I had the pleasure and privilege to attend yesterday’s meeting of the Broadcasting Board of Governors as a member of the public. The session featured two fascinating presentations and discussions. First, Voice of America Director David Ensor gave an inspirational presentation on the mission, goals, accomplishments, and challenges facing the Voice of America. Later, we listened to an insightful panel on Technology and Innovation that featured Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, Coordinator for International Information Programs at the U.S. Department of State Macon Phillips, and Chief Technology Officer for the Atlantic Media Group Tom Cochran.

Among the many important issues raised in these discussions are a few key themes facing all of us who are engaged in the practice of public diplomacy. The dominant issue – as is often the case – is how to use our scarce resources most effectively. For the VOA, an organization with a multiplicity of missions (providing independent news, explaining U.S. policy, teaching English, training journalists, etc.) operating all around the world, this requires difficult choices on which audiences to target and which missions to prioritize. David Ensor pointed out, for example, that VOA recently cut the Croatian service after assessing that we have higher priorities elsewhere and that the audience there has ready access to other sources of independent news. Another way to make the most of limited resources would be for VOA to explore partnerships with like-minded media outlets and other organizations engaged in English teaching and journalism training (including the U.S. Department of State and USAID). Asked about the value of particular programs and broadcasts on American music, David Ensor gave a passionate and largely persuasive (in my view) defense of how these programs help Americans connect with foreign audiences around the world.

The VOA discussion featured a number of comparisons with broadcasting organizations of other countries like CCTV, Russia Today, and the BBC (usually to illustrate that VOA is relatively underfunded). BBG Governor Matt Armstrong highlighted a key point, however, when he remarked that unlike those organizations the VOA is not seeking to secure a permanent market share in each of its overseas areas of activity. Instead, the VOA is ultimately seeking to put itself out of business in each of these areas by encouraging the development of local, independent media sources (i.e., by “exporting the First Amendment”).

Unspoken but implied was the suggestion that we should be careful when we compare VOA and its sister broadcasting agencies with official foreign broadcasters. VOA Director David Ensor agreed, in part, but countered that we may ultimately decide that we should maintain at least some presence in order to explain U.S. policies. Personally speaking, I agree with Matt Armstrong and am inclined to believe that the U.S. Department of State can fulfill that function in said markets, while perhaps relying in part on VOA’s English-language resources available at the Washington headquarters and its online platforms.

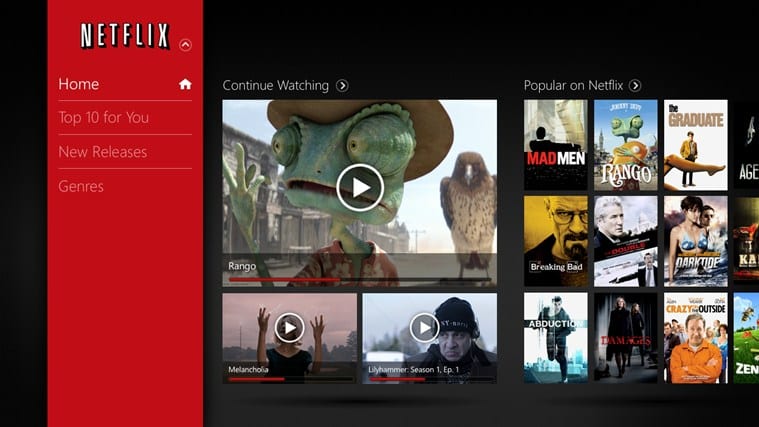

The Innovation panel also proved exceptionally interesting, highlighting the significant challenges that technology poses for the BBG (and the State Department). Netflix CEO Reed Hastings emphasized the need to always keep the big picture of the future in mind if we hope to develop tools and programs that will be effective in the future. He noted, for example, that Netflix always believed that streaming video was the future of the company and that snail mail DVDs were always considered an interim measure. Likewise, we in public diplomacy should all keep in mind that in another 20 or 30 years the internet will be everywhere, even overseas (a remark that caused many in the audience to ponder a future when television and radio will simply be obsolete).

Another interesting theme was the benefits and dangers of “personalization” (using technology to deliver customized content to individuals as Netflix does) and “balkanization” (the development of virtual “gated communities” in which there are no longer public squares and water coolers where people are forced to debate issues of general interest).

Finally, IIP’s Macon Phillips, who recently joined the State Department after heading up the White House’s digital outreach efforts, described the challenges that he faces of leveraging technology and our public diplomacy personnel and platforms overseas to engage foreign publics in a meaningful way that not only communicates, but also helps advance our policies. He mentioned an initiative that he helped launch at the White House – “We The People” – that allows people to submit petitions and, if they gather enough signatures, receive a response from the White House. A possible model for a similar State Department initiative?

A couple of great discussions and a lot of food for thought!

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the State Department or the U.S. government. The author is a State Department officer specializing in public diplomacy, currently detailed to the IPDGC to teach and work on various Institute projects.