Within the first 100 days of office, Donald Trump formally withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and notified Mexico and Canada of his intentions to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

All contending presidential candidates ran on anti-TPP platforms during the 2016 election. In fact, Trump’s pledge to bring jobs back to the states was what attracted his core voter base.

Many oppose multi-lateral trade agreements, such as the TPP and NAFTA, in fear that they will damage our manufacturing sector and enlarge the trade deficit. Others support these agreements in hope that they will grow exports and propel our economy forward.

The difficulty is that there is little alignment between those two groups, and finding common ground on what exactly these trade agreements will and won’t do is extremely complex. Debating the economics behind the deal has proven especially futile and even beside the point.

Today’s trade agreements are rarely about trade alone. Rather, they are long-term public diplomacy efforts which follow a relational framework in bringing nations together.

So, let’s resurrect the TPP for a few minutes and discuss exactly what will happen to those Pacific Rim relationships in our absence.

A primary objective of the TPP was to exert control on China. This objective has been a U.S. foreign policy goal since the Nixon era, and according to The Atlantic, is only becoming more difficult to manage. Of main concern has been the enormous increase in China’s global trade surplus since the 90s, a topic that Trump has not shied away from.

Trump has declared on numerous occasions that China would’ve benefited from the agreement due to back door channels, but by leaving the deal we’ve opened the front door to China ourselves. According to the New York Times, China has much more space to fortify its economic supremacy in Asia with the U.S. in standstill. One Washington Post article found that a deal between China and Japan alone could jeopardize $5 billion in U.S. dollars.

After speaking with experts on the topic, Politifact ranked Trump’s TPP China claim to be “Pants on Fire” false. In other words, it was virtually impossible that China could have taken advantage of the TPP in a major way.

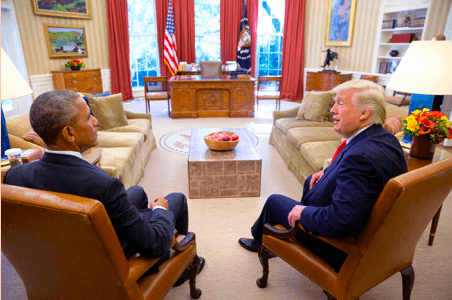

However, what’s potentially more devastating than deserting this longtime foreign policy goal, and aiding China in its newfound economic foothold, is the lack of support we’re showing our allies in the region. As much as Obama worked to control China, he worked to tap a growing region and to forge meaningful partnerships in that area of the world.

The TPP would have been the first time that both small and medium-sized American businesses, and TPP member-state businesses, would’ve had access to nearly half of the world’s economies. The biggest driver for most TPP participants was access to the U.S. market. According to CNN, America’s GDP accounts for 69% of the combined GDP of the member countries. Our departure from the agreement is a major let down to many of these emerging economies.

Opponents of the TPP have called the agreement a “job killer,” but, leaving the deal is exactly what may hinder job growth. As Forbes explains, leaving the TPP may lead to a later trade war wherein prices will shoot up and drive down demand, limiting the spending of American consumers and leading to fewer jobs.

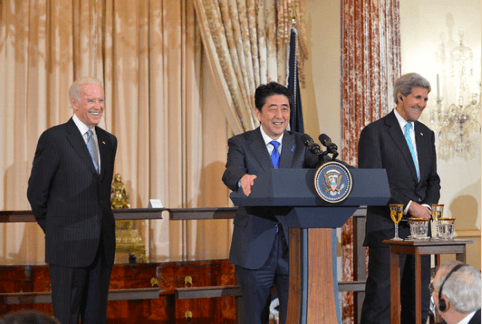

What’s more is that the possibility of a trade war is not entirely outlandish. One New York Times article speaks to our now strained relationship with Japan and the fear that the lack of an agreement will bring on the trade wars we saw in the 1980s, back when our nations saw one another as economic opponents.

Whether or not the TPP would have been as financially fruitful as the Obama administration expected does not get to the heart of the issue. As Defense One explains, free trade deals are most valuable due to their ability to strengthen diplomatic relations and reduce future conflict, not their ability to produce dramatic economic welfare.

TPP was by no means a perfect deal. The agreement became an extremely intricate arrangement concerning pharmaceutical regulations to environmental protections. According to Senator Warren and other elites, the deal even ran the gambit of allowing for corporatocracy through secret tribunal clauses outlined in the deal.

However, by pulling out of the agreement, we’ve not only added to our wavering credibility by abandoning yet another foreign policy objective, but rendered our Pacific Rim allies ripe for the picking.

With all this in mind, it’s important to remember that the TPP was not the only multi-lateral agreement in the works. Coming up next are the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and Trade in Services Agreement (TISA).

With a delicate global order hanging in the balance, it’s crucial that America does not lag in foreign commitment. Unfortunately, and unless Trump suddenly drops his protectionist stance, pushing for these trade agreements might be almost entirely up to our foreign partners.

To sway public opinion, a departure from the relational framework which grounds these agreements may be best. Instead, our foreign allies should work on deploying multi-platform information campaigns, where they can engage the American public directly and explain to U.S. citizens why free trade is valuable to U.S. foreign policy efforts at large. Better yet, these information campaigns can take a note from Vox and explain how our manufacturing sector has been dying since the 1940s and is not a result of trade agreements between our nations.

Persuading the American people will not be easy. According to Pew, Americans have been wary of foreign engagement since the Cold War. But, if the TPP has taught us anything, it’s that an imperfect situation is still worth exploring.

With stronger social media campaigns, more op-eds from legitimate elites and a proliferation of accessible literature on the issue, foreign entities can control their messaging and begin to alter American perception away from Trump’s.

Caveat: The views expressed in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication or the George Washington University.

Trade agreements are important opportunities for multilateral discussions and mutual interest efforts. I was disappointed that the TPP was taken off the table for a number of reasons and I think it is interesting to consider this from two angles: relations between states and relations with foreign publics. For the latter, PEW global attitudes survey data has shown strong support for the TPP in member states, with US publics being the least supportive: http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/06/23/3-asia-in-focus/#tpp-americans-among-the-least-supportive. The implications of pulling out of this deal extend to US foreign credibility and general approval abroad.

Thanks Alexa! Did you also notice the gender disparity found in that PEW article. I wonder why that is…

I agree with you on the merits of free trade, so I think it is important to consider who—if not the U.S.—is taking advantage of the public diplomacy benefits of free trade. Germany, which is one of the few remaining major western democracies to remain globally-faced, is well-positioned to step in where America did not (http://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-germany-tpp-trans-pacific-partnership-trade-547137). It seems that whenever the U.S. lets a PD opportunity pass us by, we are simply passing on the opportunity to another nation.

A very informative article. I think you hit the nail on the head when you say “how our manufacturing sector has been dying since the 1940s.” The United States’ economy has evolved, and most of the jobs have moved to the third sector of the economy – services. And since the developing countries have been making economic progress, their economies have been evolving from the primary sector (raw resources) to the secondary sector (manufacturing). There is no point in isolating the US and trying to bring back manufacturing jobs, because high priced goods made in the US will not be able to compete with cheaper goods on the market.