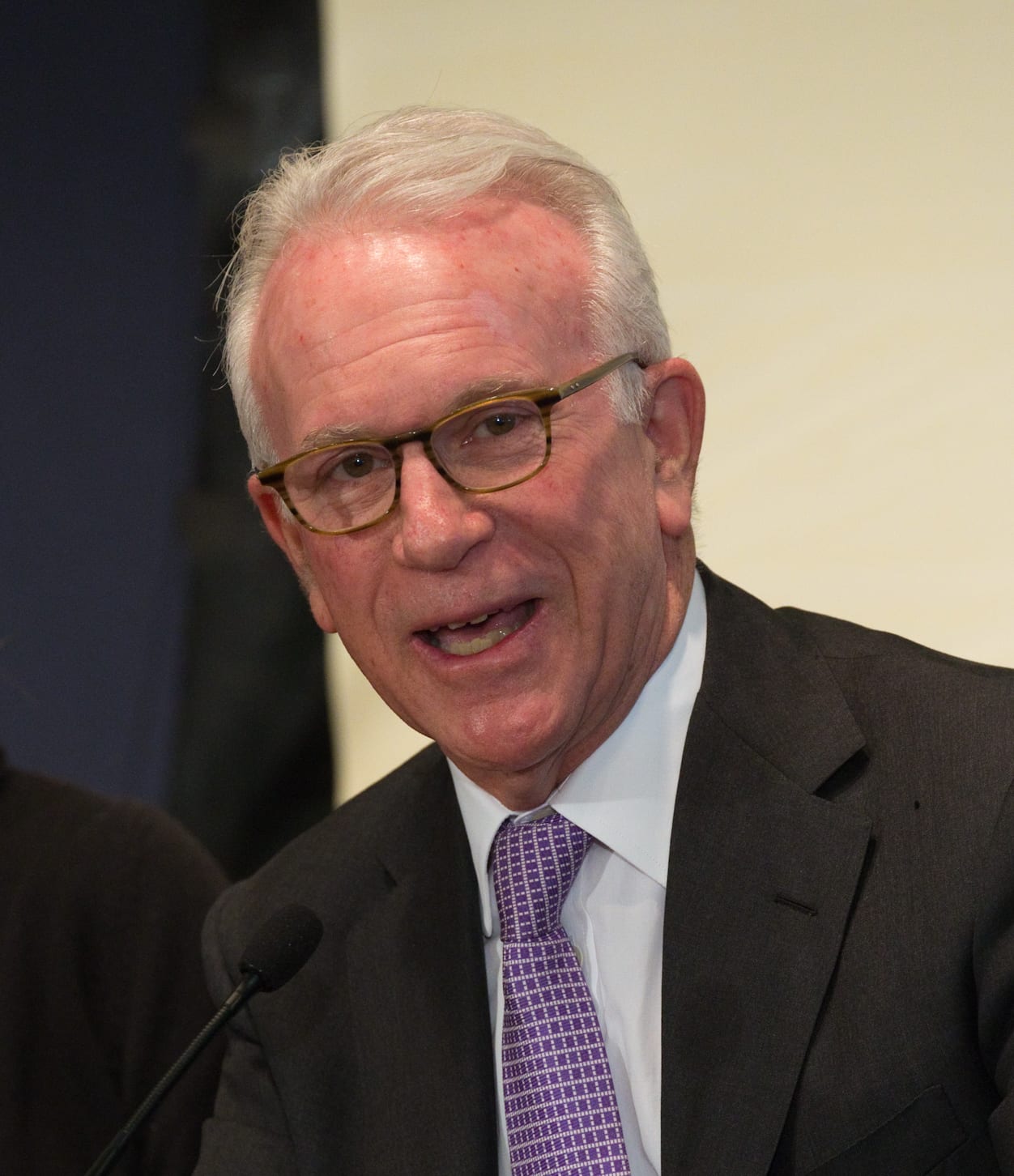

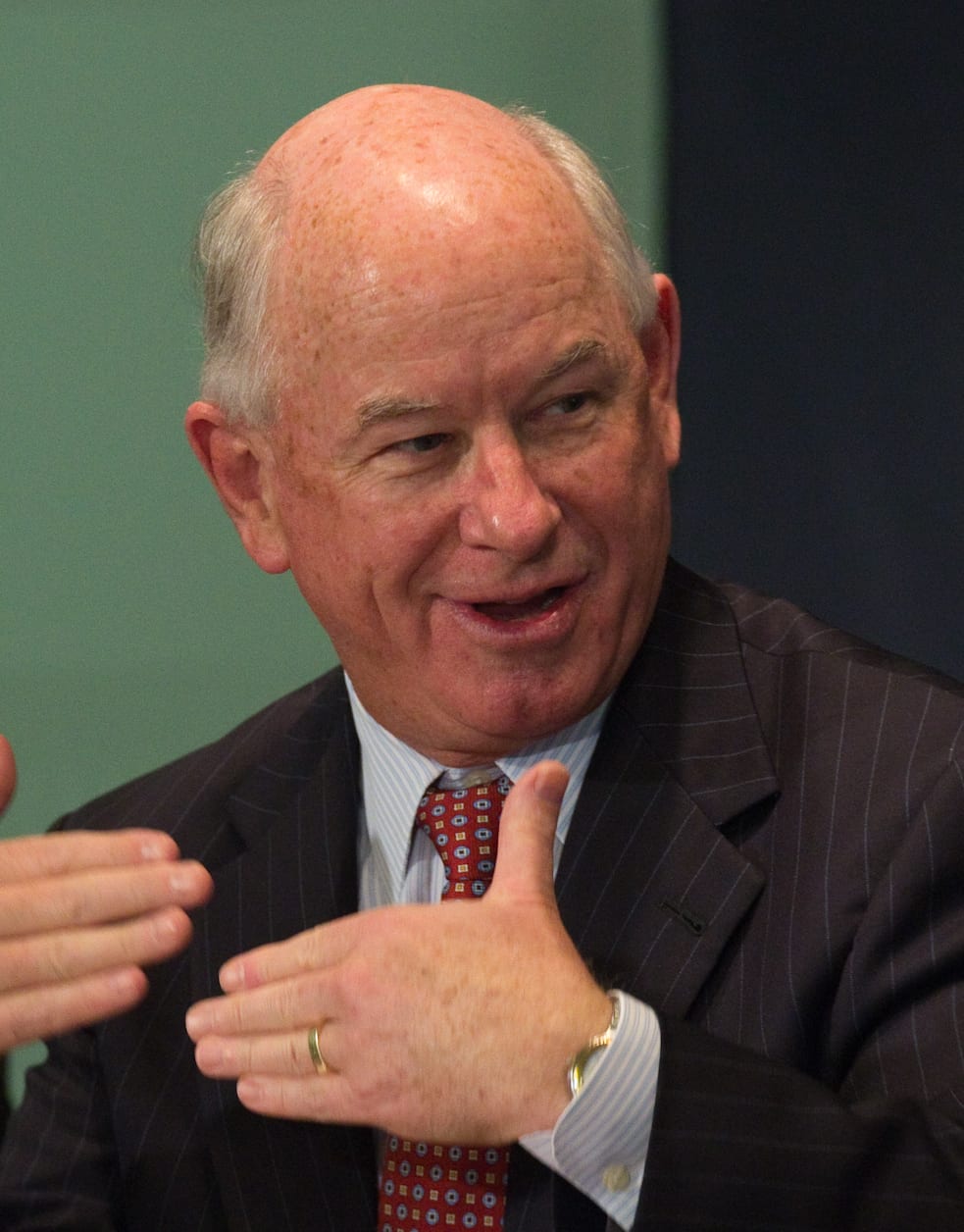

On November 13, IPDGC had the privilege of sponsoring Public Diplomacy: the Next Four Years, a terrific “insiders” discussion featuring two former Under Secretaries of State for Public Diplomacy (James Glassman and Judith McHale), a key Senate senior committee staffer (Paul Foldi), and a former State Department Assistant Secretary / spokesperson (Philip “PJ” Crowley). These are all people who not only have a vision of what America’s public diplomacy can and should do, they also know a lot about what it actually does.

On November 13, IPDGC had the privilege of sponsoring Public Diplomacy: the Next Four Years, a terrific “insiders” discussion featuring two former Under Secretaries of State for Public Diplomacy (James Glassman and Judith McHale), a key Senate senior committee staffer (Paul Foldi), and a former State Department Assistant Secretary / spokesperson (Philip “PJ” Crowley). These are all people who not only have a vision of what America’s public diplomacy can and should do, they also know a lot about what it actually does.

Panel members enthusiastically debated the role and strengths of contemporary U.S. public diplomacy. One area of complete agreement: two-way engagement is a big priority over one-way messaging. Another consensus: information technology is a game-changer in diplomacy and foreign affairs.

Key Takeaway: Signficant discussion revolved around how diplomacy itself – not just public diplomacy – is changing. The implication was clear that diplomacy must change even more in this modern world of globally shared challenges and exponentially more information networks.

Here is one blogger’s observations on key points and highlights from this IPDGC-sponsored panel:

1) Consensus: Engagement and relationships trump one-way messaging:

1) Consensus: Engagement and relationships trump one-way messaging:

McHale: The world has changed [and] we will not be able to move our foreign policy goals and objectives forward without having a better relationship, better understanding and engagement with people all over the world. We simply can’t do it.

Crowley: [re: tweeting with Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez] By doing that, the folks in [the Western Hemisphere Affairs Bureau] will go, why are you doing that? I’d say, it is generating a debate within Venezuela. And one of my colleagues said, when you wrestle with a pig you get dirty. I go yes, but this is a debate that we will ultimately win. [We] have to be willing to let our diplomats engage in this debate and quite honestly that’s a phenomenon that will happen.

Crowley: [re: tweeting with Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez] By doing that, the folks in [the Western Hemisphere Affairs Bureau] will go, why are you doing that? I’d say, it is generating a debate within Venezuela. And one of my colleagues said, when you wrestle with a pig you get dirty. I go yes, but this is a debate that we will ultimately win. [We] have to be willing to let our diplomats engage in this debate and quite honestly that’s a phenomenon that will happen.

Foldi: Sometimes I think the department falls into this trap of, “well we put all things out on a web and then we let people comment on them.” Well that’s not what they really want, they want to engage in a conversation

Foldi: Sometimes I think the department falls into this trap of, “well we put all things out on a web and then we let people comment on them.” Well that’s not what they really want, they want to engage in a conversation

Glassman: You look for those avenues where you can pursue those conversations, where you can build relationships even in very difficult and challenging parts of the world for us.

But at least one voice made the case for “messaging” — when it is done in new, relational contexts:

Glassman: I realized that simply standing up and preaching at people… is not a very effective way to communicate. [Foreign audiences] don’t want to listen to you, to Americans preaching at them. But rather a better way to communicate is to use American authority, such as it is, to convene a large, broad and deep conversation in which American messages are … injected [or] distributed among other messages

Glassman: I realized that simply standing up and preaching at people… is not a very effective way to communicate. [Foreign audiences] don’t want to listen to you, to Americans preaching at them. But rather a better way to communicate is to use American authority, such as it is, to convene a large, broad and deep conversation in which American messages are … injected [or] distributed among other messages

So the emphasis is on relationships and engagement. And whether focused on advancing foreign policy goals or debating policies and ideologies at the head of state level, the panelists are not just talking about public diplomacy, they’re talking about all of diplomacy.

2) Another area of agreement: Information technology as a game-changer:

McHale: The world has changed so dramatically and so fundamentally with … technology and with information and power now being widely dispersed. We have got to find better ways of influencing foreign populations or we simply can’t go forward. [For example], right now in this room there is nobody here who can raise their hand and say ‘I can identify who was the leader of the Egyptian revolution.’ Because there wasn’t one; it was coalitions, ever changing coalitions of interests.

Glassman: And second, it’s just amazing, we … have lucked into this world — and we haven’t “lucked” into it, but the tools are there, tools that did not exist ten years ago. The tools for communicating in a public diplomacy 2.0 way.

3) Defining the core goal of public diplomacy: is it “Benefit of the Doubt?”

Paul Foldi and PJ Crowley both focus on the perceived gap between words and deeds as a major challenge for public diplomacy. Foldi describes how a country that builds up its soft power can get over specific policy hurdles:

Foldi: It can take years to get what I call ‘benefit of the doubt,’ which I believe is the goal of public diplomacy. So that when your country does something or has a policy that seems counterintuitive to the rest of the world, they’ll go “oh, but they are the United States — so maybe they’re doing this [thing we don’t like], but for the most part we agree with them.” And to me … it’s a question of can we get back into the ‘benefit of the doubt’ category for many of these countries?

Foldi: It can take years to get what I call ‘benefit of the doubt,’ which I believe is the goal of public diplomacy. So that when your country does something or has a policy that seems counterintuitive to the rest of the world, they’ll go “oh, but they are the United States — so maybe they’re doing this [thing we don’t like], but for the most part we agree with them.” And to me … it’s a question of can we get back into the ‘benefit of the doubt’ category for many of these countries?

(Note: Foldi’s view – creating the benefit of the doubt – strikes me as something a lot of public diplomacy practitioners would agree with. I think many of us would see this is as an achievable goal in many overseas contexts, and we would consider the public diplomacy ‘toolkit’ useful in pursuing this goal.)

By contrast, PJ Crowley focuses not on helping contextualize policies that are unappreciated abroad as being inconsistent with shared values, but rather on trying to eliminate them:

Crowley: Ultimately the best public diplomacy is … policies that reflect your interests and your values and [when] the gap between what we say and what we do is as narrow as it can be. … [One] of the great challenges for public diplomacy is to bridge the gap between words and deeds, to narrow that to the extent possible. … [Polling trends] should inform what our short term and mid term actions are.

Crowley: Ultimately the best public diplomacy is … policies that reflect your interests and your values and [when] the gap between what we say and what we do is as narrow as it can be. … [One] of the great challenges for public diplomacy is to bridge the gap between words and deeds, to narrow that to the extent possible. … [Polling trends] should inform what our short term and mid term actions are.

Meanwhile, Glassman and McHale reject a polling-driven “popularity contest” approach, maintaining that targeted PD efforts can and should be used to further specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

Glassman: I don’t think that favorability ratings in the Pew survey are evidence of whether we are doing something wrong or right. [I tried] to disabuse people of that notion and rather to focus attention on what public diplomacy can do to achieve specific ends that are part of [our] goals in foreign policy and national security policy; that’s what public diplomacy is supposed to do.

McHale: I’m certainly in agreement with Jim on this issue, it’s not a popularity contest … that is absolutely the wrong focus.

As the panelists fleshed out their ideas, however, I heard each one suggest support for Foldi’s “benefit of the doubt” role for public diplomacy:

Crowley: we will always be challenged …for example Indians have expectations in terms of the US policy towards Pakistan or Pakistan has expectations towards the US policy towards India, and those two… do not easily coexist. And when… you sit in between those two long time antagonists, you are going to end up disappointing both of them to some degree or another.

McHale: There were many areas where … we do find areas of common interest, science, technology, education, all of those areas. … [N]aturally you are going to encounter a lot of resistance and what have you but that’s no reason to give up. And you look for those avenues where you can pursue those conversations, where you can build relationships even in very difficult and challenging parts of the world for us.

Glassman: [A]s Senator Fulbright said, the Fulbright programs teach empathy, standing in somebody else’s shoes. I’m a huge believer in that and I think that is valuable. (But should two thirds of the money be spent on that?)

Glassman (again): [A]s president Obama said right in the beginning … we need to focus on mutual interest and mutual respect and there are many things that we can get done in that fashion.

All of these comments reflect the idea that some U.S. policies will inevitably be viewed by some other countries as inimical, unfair, and/or a betrayal of U.S. stated values — so concentrating on other interests and values that we do share, as well as working to promote mutual empathy and understanding, is essential.

4) This is really about “all of diplomacy”:

It is worth repeating Judith McHale’s observation about the Egyptian revolution: “right now in this room there is nobody here who can raise their hand and say ‘I can identify who was the leader of the Egyptian revolution.’ Because there wasn’t one, it was coalitions, ever changing collations of interests.”

Pair this with Crowley’s discussion of high-level public communications, for example those tweets with Hugo Chavez. He makes clear that informal and globally available public communication by heads of state and top diplomats (not to mention powerful business leaders and highly influential NGO advocates) is here to stay.

Pair this with Crowley’s discussion of high-level public communications, for example those tweets with Hugo Chavez. He makes clear that informal and globally available public communication by heads of state and top diplomats (not to mention powerful business leaders and highly influential NGO advocates) is here to stay.

These panelists emphasized, in other words, that understanding and responding to events such as the Egyptian revolution or debating Hugo Chavez in his domestic political arena is not only the work of public diplomacy, it’s at the center of diplomacy and foreign policy. And engaging in this public sphere has to be a focus of the whole State Department, not just its public diplomacy bureaus.

Glassman makes the case that, in this new environment, using the tools of public diplomacy is a notably low cost / high impact strategy and should be expanded: “There are ways to move money within the State Department budget that would make the Department as a whole more effective by putting more emphasis on public diplomacy. … One of the reasons that I strongly believe that we need more public diplomacy … is because at a time of tight budgets, it’s the most cost effective way to achieve those national interest goals that I talked about.”

Glassman makes the case that, in this new environment, using the tools of public diplomacy is a notably low cost / high impact strategy and should be expanded: “There are ways to move money within the State Department budget that would make the Department as a whole more effective by putting more emphasis on public diplomacy. … One of the reasons that I strongly believe that we need more public diplomacy … is because at a time of tight budgets, it’s the most cost effective way to achieve those national interest goals that I talked about.”

He takes that idea further to suggest that Embassies themselves may be obsolete.

Glassman: And the other thing that I would just throw out to you is whether in an era of social media and very, very fast communications, whether we should be spending as much money as we are in general at the State Department on things called embassies. Okay it made a lot of sense 100 years ago, but does it make sense today to have this edifice and this very complicated kind of arrangement where people go for a few years and live there, as though they couldn’t possibly influence people in those countries if they didn’t live there?

No doubt many would find controversial the idea that one can influence people whom one has never met face to face, much less grown to know better over time. But on closer examination, is Glassman really saying that diplomats don’t need to go abroad and meet people? Is it possible to envision an engaged diplomacy involving both face to face and online interactions that does not involve the traditional Embassy model?

I’m not sure. (What do TakeFive blog readers think?)

Advocates of ‘new approaches to public diplomacy’ often end up by proposing new approaches to diplomacy itself. As these excerpts from last week’s expert panel discussion show, our panelists at the IPDGC event were no exception. (And there was much more rich discussion that can be found on the event video or in the transcript.)

Yes, they were unanimous on the importance of existing public diplomacy efforts, and there was little disagreement on the impact of valued public diplomacy tools (exchanges, social media).

At the same time, these experienced public diplomacy experts expressed a range of ideas – some quite provocative – about how approaches rooted in public diplomacy are particularly appropriate for the 21st century challenges of U.S. diplomacy overall.

It will be great for IPDGC and other groups interested in the theory and practice of public diplomacy to get more such debates launched in the wider arena of foreign affairs / diplomacy.