This post is authored by GWI’s Amaeka Effiong, Amal Hassan, and Jessie Weber

The room is silent and serious. “As feminist researchers, we make visible harms,” says Dr. Shirley Graham, the Director of the Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs (GEIA), from behind the podium. She pauses and paraphrases award-winning author and human rights activist Azar Nafisi. “Storytelling can save us,” Graham says, leaning towards the audience, and then looks to Nafisi, who gives her a small smile.

In recognition of International Women’s Day (IWD) this year GEIA, in partnership with the Global Women’s Institute, organized a discussion with Nafisi, moderated by three young women (GW undergraduate students Elena Maoilani and Diya Mehta, and Elliott School alumna Roksana Verahrami) as a reflection of the author’s commitment to continuously engage with women of the next generation. Though IWD celebrations are often joyous, however today’s is tempered by the recent publication of a sobering UN report announcing that, after accounting for recent events deepening gender disparities, the world will not achieve gender equality for another 300 years. Of particular focus in this discussion is the over six months of protests in Iran against policies that violently affect women, girls, and minority communities most acutely within the country, but ultimately affect all of its citizens.

Nafisi, whose mother was one of the first women in the Iranian parliament in 1963, rises and takes her stand at the podium to tell us how, so often, “women are the canaries in the mine” where oppression is developing. She reflects upon how on this day in 1979, women in Tehran woke up and walked into their streets to celebrate IWD. The celebration evolved into a protest against the totalitarian regime being imposed upon them, and many women experienced violent retaliation for their participation. Nafisi points to this as one of many examples of why it is irresponsible for foreigners to excuse instances of violence and inequality by writing them off as cultural differences, such as the lowering of girls’ marriage age in Iran from 18 to a mere nine years old. She challenges the room: “Who are you to tell me what kind of freedoms I want or deserve?”

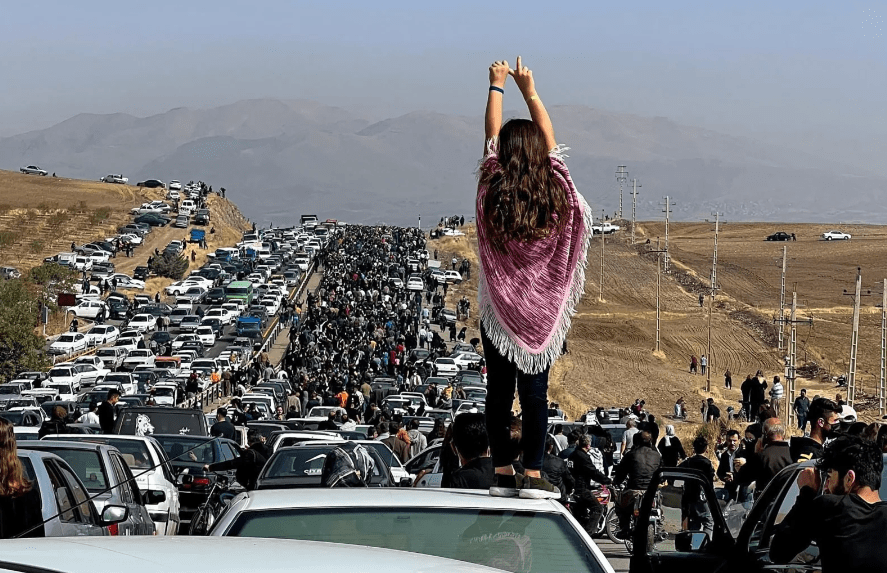

When the women of Iran marched in Tehran on the 8th of March, 1979, they were shouting chants decrying the call for mandatory hijab (religious covering), saying to the watching world, “Freedom is neither Western nor Eastern, it is global,” as they fought for the autonomy to choose whether they are veiled. These protests changed the narrative that the regime wanted to write not just about the women and girls of Iran, but about its whole population, as all demographics took to the streets to protest alongside them.

Today, the streets of Iran are again filled with protestors of all identities. This time they are shouting the Kurdish rallying cry “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî,” or the Farsi translation “Zan, Zendagi, Azadi,” which has been heard around the world as “Women, Life, Freedom,” a cry against oppressive regimes and international unwillingness to acknowledge the harms they inflict. This is especially pertinent at a time when the rights of women, girls, and all demographics are being threatened in the world, from women and girls being denied education and working opportunities in Afghanistan, to journalists in Myanmar being targeted for their work, to civilians in Yemen being attacked in bombings.

Nafisi reminds us of Iran’s history of artistic expression and of activists’ longstanding push for the liberation of all people in Iran. “We don’t need to look to the West for freedom–we go to our past,” Nafisi says, numbering not only instances in which Iran’s women and girls have chosen life, and, in doing so, have chosen resistance, but also Iran’s rich literary history that has, again and again, indicated this love of life and of freedom as a vein that runs powerfully through the core of true Iranian culture. After all, Nafisi says, “Literature and art are conclusive evidence that we’ve lived.”

This year’s IWD may be heavy with solemnity, but it is also marked by a certain degree of hope. As Nafisi puts it, the protests we see today, like the protests we remember from yesterday, are not rooted simply in desires for different leadership or policies, but in the unwillingness to relinquish one’s right to exist as a human being. “To resist the forced actions of the regime [in Iran],” she says, “is to live.” The often innate capacity of women and girls to alert communities to inequalities, and the collective power that comes when community members of all identities stand alongside them calling for justice, is as moving as it is unshakeable. This time next year, we hope to be celebrating the victories that these brave voices have rendered in their communities and, in their inevitable ripple effect, across the world. For now and always, we stand alongside them in solidarity, crying Woman, Life, Freedom.

Amaeka Effiong is a Research Intern at the Global Women’s Institute working specifically on the Empowered Aid Project, and a 4th-year undergraduate student at George Washington University studying International Affairs with a concentration in International Development and a minor in Human Services and Social Justice. Most of her studies, previous internships, and volunteer experience have centered around the continent of Africa and tackling the subject of international development in a manner that empowers and places value on women, people of color, and other marginalized communities. Amaeka currently organizes with Ward 2 Mutual Aid to bring necessary supplies to unhoused neighbors near GW’s campus and has served at organizations such as Jumpstart and DC Action for Children that seek to improve education quality and access in the US. Post-graduation, Amaeka will further her passion for education by serving as an and Ethics and Leadership Teaching Fellow at the School for Ethics and Global Leadership in London, UK.

Amal Hassan is a Research Assistant at the Global Women’s Institute, supporting the institute’s conflict-related GBV programs: the Building GBV Evidence Program and the Empowered Aid Project. Amal’s unique experiences as a first-generation Somali American woman have guided her interests in the intersection between health equity, gender-based violence, and survivor-centered social justice. Amal hopes to continue her work in gender-based violence research and safeguarding in humanitarian contexts utilizing culturally sensitive and trauma-informed approaches in her post-graduate career. Amal is currently pursuing a Master in Public Health (MPH) concentrating in Maternal & Child Health at the Milken Institute of Public Health at The George Washington University.

Jessie Weber is a Research Associate with GWI, who prior to joining the team worked with various grassroots efforts to support displaced populations in northern France. Within the US, she has seven years of experience volunteering with grassroots organizations supporting immigrant populations across the northeast and has a professional background in legal and psychosocial support for veteran populations, including two years working with the Center for Integrated Healthcare to support behavioral health treatments for post-traumatic stress and substance use disorders. Her professional interests center on bridging gaps of accountability to and collaboration with affected populations in research and programming, and on the inherent right of all people to accessible, individually-adapted health services, including mental health and psychosocial support.

Be First to Comment