Published by the Global Women’s Institute in collaboration with the International Development Law Organization (IDLO).

As researchers, advocates, and practitioners, we know that most survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) will never report that violence to any authority. In the majority of countries with available data, fewer than 4 in 10 women who experience violence seek help of any sort and, among those who do, fewer than 10 percent report their assault to the police (UN Women, IDLO, World Bank and Task Force on Justice 2019, p. 23). New data on violence against women during COVID-19 confirms that only 1 in 10 women would seek help from police if they experienced domestic violence (UN Women 2021, p.14).

Those survivors who seek justice in the formal or informal systems navigate myriad challenges in doing so. These challenges include social norms that stigmatize or blame survivors, community pressure to withdraw a report, fear of reprisals, lack of economic resources, and distrust of formal institutions. They also include constraints within justice institutions, such as corruption or lack of judicial independence, mistreatment of survivors, evidentiary challenges and a lack of forensic capacity and, in many contexts, a general culture of impunity.

These challenges are only made more complex in times of crisis, be they situations of conflict, climate change, impunity, corruption or economic insecurity. It has been shown that in conflict and fragile contexts the risk of intimate partner violence can increase (Swaine, 2018), in some cases by as much as threefold (Ellsberg et al., 2020). Over seventy percent of women experience GBV in humanitarian or conflict contexts (Global Humanitarian Overview 2022). Survey data now confirms the many reports from support services, health practitioners or media that violence against women and children has increased since the outbreak of COVID-19 (UN Women 2021).

Justice systems often break down in times of conflict or crisis, leaving women few options for recourse when they have experienced violence. Factors that further impede women’s access to justice in complex contexts include inadequate and discriminatory legal frameworks and procedures, inadequate availability and resourcing of formal justice institutions and services, discriminatory practices and lack of accountability within customary and informal justice systems that are most accessible for women, entrenched patriarchal social norms, practices and attitudes, lack of survivors’ awareness of rights and availability of support services, increased financial constraints and heightened safety risks (GBV AoR, Global Protection Cluster 2020; and UN Women, IDLO, UNDP, UNODC, World Bank and The Pathfinders 2020). Thus, in these situations, women are more likely to experience violent crimes and less likely to receive justice support (UN Women, UNDP, UNODC, OHCHR 2018).

Gaps in current research. Fragile, conflict and post-conflict settings, health emergencies and other complex situations represent gaps in current research and practitioners’ understanding of how to effectively respond to or prevent GBV. Increasingly, however, the gender, justice and development community is focusing on how to address the glaring justice gap for women and girls who experience gender-based violence in complex situations in a way that keeps them, and their rights and needs, at the center.

Can justice really help to end GBV when the challenges are so vast?

Yes! Justice is a key component of the multi-pronged, comprehensive effort that is required to end violence against women and girls. To begin with, laws against GBV matter. Research on 84 countries found that the existence of a law against domestic violence is associated, on average, with a 3.7 percent lower national rate of physical intimate partner violence (UN Women, IDLO, World Bank and Task Force on Justice 2019, p.56). The prohibition of GBV can have a preventive effect.

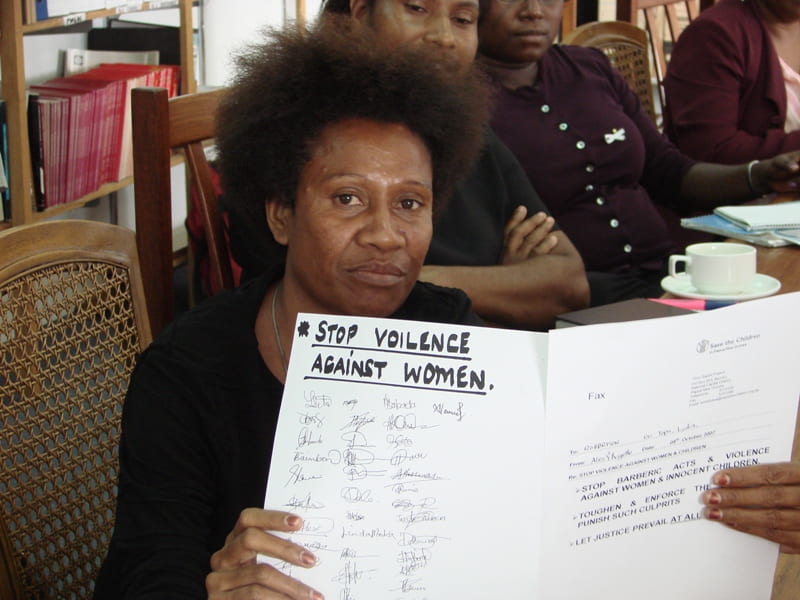

“Once the husbands see that the law is involved, it tends to deter their behavior.” –Key informant coordinating a key donor program in Papua New Guinea (PNG)

A research team led by Mary Ellsberg found that, 20 years after the adoption of a law to protect victims of domestic violence in Nicaragua, physical domestic violence against women had declined by 70 percent. Their unique study in León showed—for the first time ever—that investments in legal reforms, special services for women, and transforming social norms can indeed prevent violence against women and girls on a large scale.

New laws are only one small (but important) part of a larger process of reform, and getting justice systems to work for survivors entails many more steps. Justice, starting with clear criminal laws on all forms of GBV and putting into place processes for their implementation, can help, if it remains centered on the survivor.

Survivor-centered justice starts with listening to women about what justice means to them. For survivors, justice may be tied to conviction and punishment, or it may be linked to truth and dignity or an acknowledgement of the harm done to them. It may also be linked to restorative justice as well as social and economic empowerment.

All measures to address GBV should be implemented with “an approach centered on the victim/survivor, acknowledging women as subjects of rights and promoting their agency and autonomy.” – CEDAW General Recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating General Recommendation No. 19

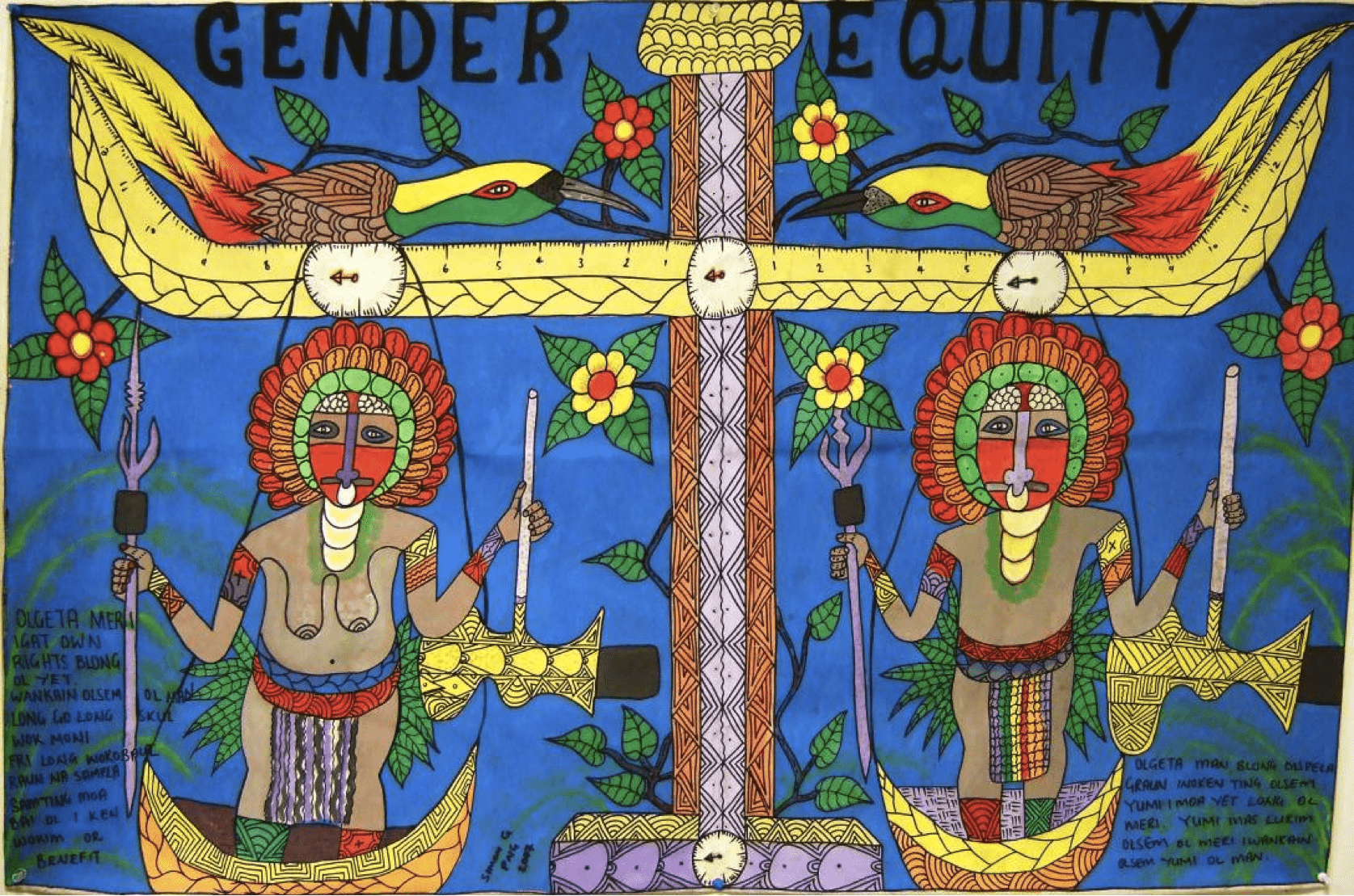

To work towards bridging the gap in knowledge on how to advance justice for survivors of GBV in complex situations, which are also some of the most violent contexts in the world, the International Development Law Organization (IDLO) and the Global Women’s Institute (GWI) initiated a joint research project in the beginning of this year. We conducted research in six countries selected for their unique complexity: Afghanistan*, Honduras, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, South Sudan, and Tunisia. A team of researchers deployed a mix of methodological approaches to collect qualitative data from a range of stakeholders, including key actors in the judiciary and civil society organizations, as well as lawyers, donors, activists, and other researchers. As we go through the findings of our research, we are already seeing how it will offer lessons on how to strengthen justice systems and keep survivors at the center. We are looking at approaches that range from legal reform, specialized justice mechanisms, protection orders, and the development of legal aid schemes for GBV survivors, as well as the role of community paralegals, services for GBV survivors in complex settings, and support for local women’s organizations.

“A lot of our stories are being told by international organizations, not by South Sudanese women themselves. There is value in creating spaces where women can share their stories themselves, can write about their experiences and the work that they do themselves without someone speaking on their behalf or for them.” – Key informant who is a member of a civil society organization in South Sudan

In the coming months, we will discuss the findings of our research highlighting the steps that can and must be taken to keep survivors at the center of all justice interventions. And in doing so, we will hope to strengthen the case that survivor-centered justice is essential for ending gender-based violence.

* This research was conducted prior to the August 2021 crisis in Afghanistan.

Be First to Comment